Peer Reviewed

A Unique Presentation of Umbilical Cord Pseudocyst

Immediately following birth, a late-preterm infant was noted to have a large umbilical cord cyst, umbilical hernia, loud cardiac murmur, and left cryptorchidism.

History. The mother only had one prenatal visit early in the pregnancy when routine prenatal laboratory testing was performed. No antenatal ultrasound was obtained at that time and no abnormal findings were noted antenatally. The infant was born at 36 weeks and 2 days gestation to a 45-year-old gravida 4, TPAL: 3 (term births), 0 (preterm births), 0 (abortions), 3 (currently living children) mother via vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery.

The infant had respiratory distress requiring positive pressure ventilation immediately following delivery. Apgar scores were 5, 7, and 9 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Examination was significant for a large, yellow, cystic swelling in the umbilical cord, a large, reducible umbilical hernia (Figure 1), a grade III/VI systolic murmur, and left undescended testis. All peripheral pulses were within normal limits on palpation and the infant had good peripheral perfusion and capillary refill following resuscitation. Four extremity blood pressures were not performed. The birth weight was 3159 g and the remaining anthropometric measurements were within normal limits.

Figure 1. Umbilical cord cyst with umbilical hernia was present at birth. There were no intestinal contents within the cyst.

The infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) from the delivery room on continuous positive airway pressure therapy with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 35%. Chest X-ray on admission to the NICU showed mild respiratory distress syndrome but was otherwise unremarkable. The infant was weaned off respiratory support within 2 hours of NICU admission and remained on room air throughout the hospital stay.

Given the loud murmur noted on initial examination, an echocardiogram was obtained on the day of birth which showed Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) with a large ventricular septal defect (VSD), left superior vena cava draining into the coronary sinus, and a patent ductus arteriosus. Ultrasonography of the abdomen, kidneys, and pelvis on the day of birth demonstrated no urachal cyst or sinus, absence of intestinal contents in the cord cyst and umbilical hernia, kidneys within normal limits, and a minimally trabeculated bladder of uncertain significance.

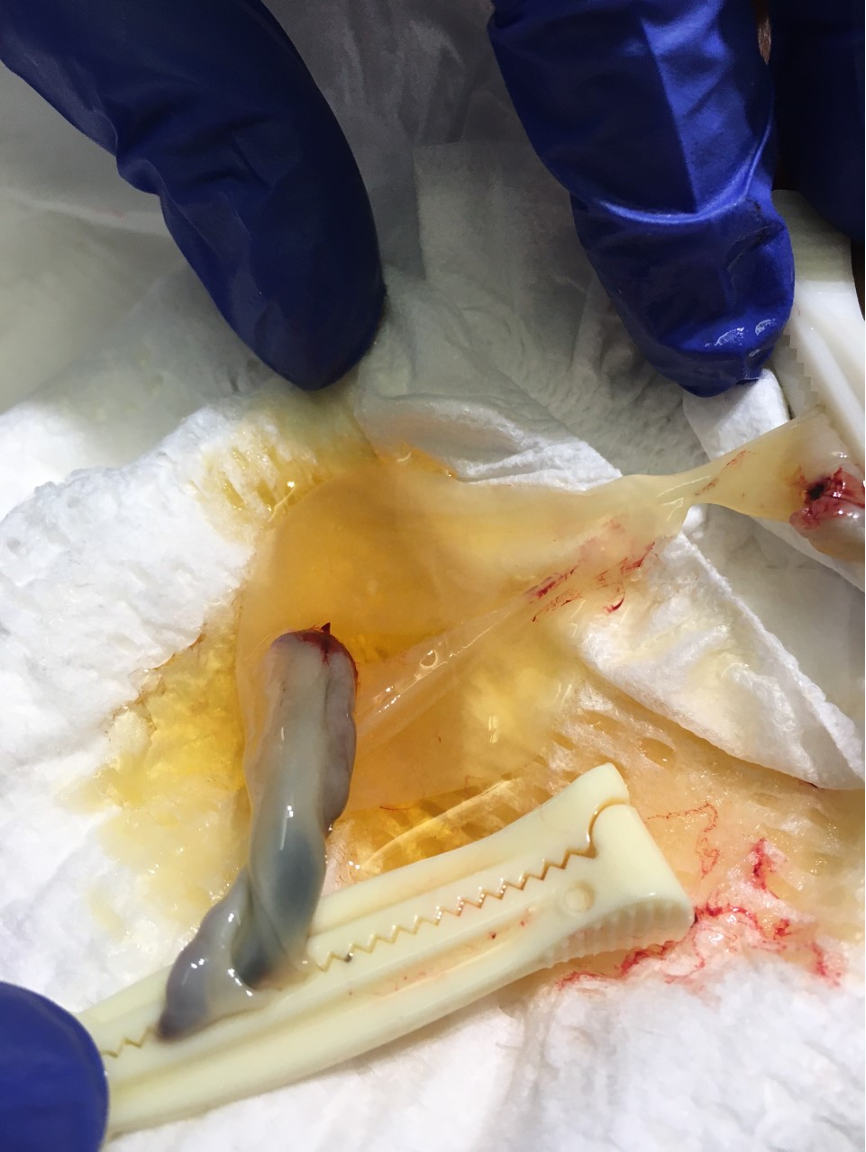

The umbilical cord was cut on day of life 1 (Figure 2). The large yellow cystic swelling in the umbilical cord measured 6 x 8 cm and the cord had three vessels. Wharton jelly-like contents without fluid were found within the cyst. There were no post-procedural complications.

Figure 2. The cyst was cut open by scalpel. Wharton-jelly-like contents without fluid were found within the cyst.

The ductus arteriosus was noted to be closed on follow-up echocardiogram on day of life 5. The infant was discharged on day of life 6. The state newborn metabolic screening was unremarkable, except for a presumptive G6PD deficiency.

Differential diagnoses. A newborn presenting with a cystic umbilical mass should arouse a high index of suspicion for an umbilical cord cyst. Cord cysts can be classified as true cysts or pseudocysts.

The differential diagnosis of a true cyst includes omphalocele, allantoic cyst, urachal cyst, and urachal sinus. There were no abdominal contents in the cyst, which ruled out omphalocele. A lack of urine in the cyst ruled out allantoic cyst. A urachal cyst and sinus were ruled out by ultrasonography. Since Wharton-jelly-like contents were found within the patient’s cyst, a diagnosis of Wharton jelly cyst was determined after excluding all pertinent umbilical cord disorders.

Treatment and follow-up. No further interventions were needed for the Wharton jelly cyst following incision and drainage.

A follow-up visit with a cardiologist 3 months later noted an increased pressure gradient across the pulmonary valve, suggesting pulmonary stenosis. A TOF repair was performed at 4 months of age. A chromosomal microarray at 4 months was within normal limits. However, this normal result cannot rule out any of the disorders not tested for on the array.

The patient was diagnosed with congenital scoliosis, which was first noted at 7 months of age, with magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating spinal fusion from L2 to L5. Surgical repair for bilateral inguinal, umbilical, and epigastric hernias, and a bilateral orchiopexy were performed at 24 months of age.

Discussion. Umbilical cord cysts are anechoic masses of the umbilical cord that can be detected by ultrasonography beginning at 8 to 9 weeks’ gestation.1 Although umbilical cord cysts can be present in any trimester of pregnancy, cysts are observed in 0.4% to 3.4% of first-trimester pregnancies and they usually resolve without adverse outcomes.2 However, further investigation, delivery planning, and coordination for neonatal evaluation is needed for cases of persistence and growth of the cyst in the third trimester in addition to distal cord edema.3 When intrauterine growth restriction or other anomalies are present, karyotype testing should also be done.4

The differentiation between a true cyst and pseudocyst prenatally is often difficult due to their similar appearance. True cysts are embryologic remnants of the omphalomesenteric duct or the allantois and have an epithelial lining.5 Pseudocysts do not have an epithelial lining and represent localized edema and liquefaction of substantia gelatinea funiculi umbilicalis (more commonly referred to as Wharton jelly). Allantoic cysts resolve spontaneously but may be associated with omphalocele, persistent urachus, or obstructive uropathy.6 Cysts in the omphalomesenteric duct can be related to defects in the abdominal wall and Meckel diverticulum. An amniotic inclusion cyst can be found inside a true cyst from entrapment of the amnion within the umbilical cord. The etiopathogenesis is unknown, but it is believed to be due to an abnormality of embryogenesis during formation of the umbilical cord.

Pseudocysts are much more common than true cysts. These are also often located near the fetal cord insertion and are primarily caused by focal degeneration within Wharton jelly. Wharton jelly is the connective tissue of the umbilical cord and is derived from the extraembryonic mesoblast. It encloses the umbilical vessels and is composed of polysaccharides, such as hyaluronic acid and carbohydrates, with glycosyl and mannosyl groups which are dispersed in small amounts of collagen.7 This enables the jelly to have a relatively firm structure allowing for contraction and distention of the umbilical cord vasculature, and it protects the umbilical cord vessels from external physical forces which could compromise their integrity.8

If the cyst is located near the placenta or the fetus' abdominal wall, there is an increased risk of fetal abnormalities.7 The presence of multiple cord cysts suggests an increased risk for chromosomal abnormalities, primarily trisomy 18, and an even higher risk if these multiple cysts persist after the first trimester, as compared with an isolated cyst.6 However, another study suggested an apparent association between congenital anomalies or lethal aneuploidies and isolated cord cysts.9 For this reason, detailed sonographic evaluation is highly recommended for both isolated and multiple cord cysts. Most cysts diagnosed during the first trimester have no clinical impact, but up to 13% of cases are associated with some structural abnormalities. This percentage increases if the cyst persists during pregnancy.6 When the diagnosis occurs at a later gestational age (during the second or third trimester), the incidence of abnormalities associated with these cases increases to 50%.6

Among non-isolated, umbilical cord anomalies, congenital heart disease may be one of the findings. While the association between an abnormal number of umbilical vessels and VSD is well-documented,10 the association between umbilical cord cysts and other cardiac anomalies is less well known. With the higher incidence of trisomy 18 among patients with umbilical pseudocyst,11 the finding of congenital heart disease in this population may overlap with the underlying chromosomal abnormalities. Currently, no known evidence suggests umbilical cord cysts to be an independent predictor of cardiac anomalies. Nonetheless, given the higher incidence of congenital anomalies among patients with non-isolated umbilical cord cysts, a thorough newborn physical examination should be performed.

Conclusion. The presence of an umbilical cord cyst conveys a broad differential diagnosis. The cyst can be classified as a true cyst or a pseudocyst; however, this is generally difficult to distinguish on antenatal ultrasound. Persistent, non-isolated, umbilical cysts after the second trimester are associated with a higher incidence of genetic abnormalities and congenital defects and warrant a thorough postnatal evaluation.

- Moshiri M, Zaidi SF, Robinson TJ, et al. Comprehensive imaging review of abnormalities of the umbilical cord. Radiographics. 2014;34(1):179–196. doi:10.1148/rg.341125127.

- Sepulveda W, Leible S, Ulloa A, Ivankovic M, Schnapp C. Clinical significance of first trimester umbilical cord cysts. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18(2):95–99. doi:10.7863/jum.1999.18.2.95.

- Shah A, Jolley J, Parikh P. A cyst in the umbilical cord. NeoReviews. 2017;18(12):e729-e733. doi:10.1542/neo.18-12-e729

- Zangen R, Boldes R, Yaffe H, Schwed P, Weiner Z. Umbilical cord cysts in the second and third trimesters: significance and prenatal approach. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(3):296–301. doi:10.1002/uog.7576.

- Kong CKY, Zi Xean K, Li FX, Chandran S. Umbilical cord anomalies: antenatal ultrasound findings and postnatal correlation. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018226651. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-226651.

- Ruiz Campo L, Savirón Cornudella R, Gámez Alderete F, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of umbilical cord cyst: clinical significance and prognosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56:622–627. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2017.08.008.

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P. Anatomy and pathology of the umbilical cord and major fetal vessels. Anatomy and pathology of the umbilical cord and major fetal vessels. In: Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer. 1995;319-377. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4196-4_13.

- Debebe SK, Cahill LS, Kingdom JC, et al. Wharton’s jelly area and its association with placental morphometry and pathology. Placenta. 2020;94:34-38. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2020.03.008.

- Smith GN, Walker M, Johnston S, Ash K. The sonographic finding of persistent umbilical cord cystic masses is associated with lethal aneuploidy and/or congenital anomalies. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16(12):1141–1147. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199612)16:12<1141::AID-PD2>3.0.CO;2-4.

- Prefumo F, Güven MA, Carvalho JS. Single umbilical artery and congenital heart disease in selected and unselected populations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(5):552–555. doi:10.1002/uog.7642.

- Vrabie SC, Novac L, Manolea MM, et al. Abnormalities of the umbilical cord. In: Congenital Anomalies - From the Embryo to the Neonate. IntechOpen. 2018. doi:10.5772/intechopen.72666.

AFFILIATION:

Jefferson Einstein Hospital, Philadelphia, PA

CITATION:

Hsiung J, Balasubramanian R, Schutzman D, Salvador A. A unique presentation of umbilical cord pseudocyst. Consultant. 2024;64(4):e2. doi:10.25270/con.2024.04.000004

Received August 15, 2023. Accepted February 6, 2024. Published online April 18, 2024.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

None.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Agnes Salvador, MD, Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University; Division of Neonatology, Jefferson Einstein Hospital, 5501 Old York Road, Philadelphia, PA 19141 (agnes.salvador@jefferson.edu)