Peer Reviewed

Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly Syndrome in a 10-Year-Old

AFFILIATIONS:

1Pediatric Resident, Nemours Children’s Hospital, Jacksonville, FL

2Family Medicine Residency Program, Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL

3Emergency Department, Nemours Children’s Hospital, Jacksonville, FL

CITATION:

Gunderson C, Roberts C, Perez V. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly syndrome in a 10-year-old patient. Consultant. 2022;62(12):e8. doi:10.25270/con.2022.08.000003

Received February 28, 2022. Accepted May 18, 2022. Published online August 2, 2022.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Carly Gunderson, DO, Nemours Children’s Hospital, 807 Children's Way, Jacksonville, FL 32207 (Carly.gunderson@nemours.org)

ABSTRACT

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is a well-established syndrome caused by incomplete development of the female Müllerian ducts in early neonatal development. The syndrome includes aplasia of the uterus and upper part of the vagina, with normal development of the ovaries and secondary sexual characteristics. We report a case of a 10-year-old patient in whom MRKH syndrome was diagnosed at an early age after ultrasonography findings of a congenital solitary renal kidney led to further imaging to assess the presence of reproductive organs. Her mother brought her to the emergency department after she developed vaginal bleeding, as her parents were previously counseled that she would never have a menstrual period or be able to bear children. Repeat ultrasonography and subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed that MRKH syndrome was a misdiagnosis and that these findings were more consistent with a diagnosis of obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome. OHVIRA syndrome is a rare congenital malformation. While MRKH syndrome is associated with absolute uterine infertility, OHVIRA syndrome differs in that preservation of fertility is possible.

Key words: OHVIRA syndrome; MRKH syndrome, Müllerian anomaly; hematometrocolpos absolute uterine infertility

Case Presentation

A 10-year-old girl with a known history of congenital single kidney, MRKH syndrome, central precocious puberty, and constipation presented to our emergency department (ED) with a 3-day history of vaginal bleeding. She also mentioned that she had worsening lower abdominal pain over the past few weeks but experienced intermittent abdominal pain “as long as she could remember.” She was less concerned about the abdominal pain, as previous physicians had told her it was likely secondary to her history of constipation.

History. Four years before presenting to our ED, the patient had undergone pelvic ultrasonography that had confirmed a solitary right kidney (noted previously on prenatal ultrasonography), as well as a fluid-filled lesion posterior to her bladder. Because of concerns for foreign body vs mass, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted for further evaluation at that time in 2017 (Figure 1). The MRI had confirmed agenesis of the left kidney but had also shown agenesis of the upper vagina with a fluid-filled, distended lower vagina. The uterus had been noted to be rudimentary, and both ovaries had been identified and appeared normal. Based on this constellation of findings, the patient had been given a diagnosis of MRKH syndrome in 2017.

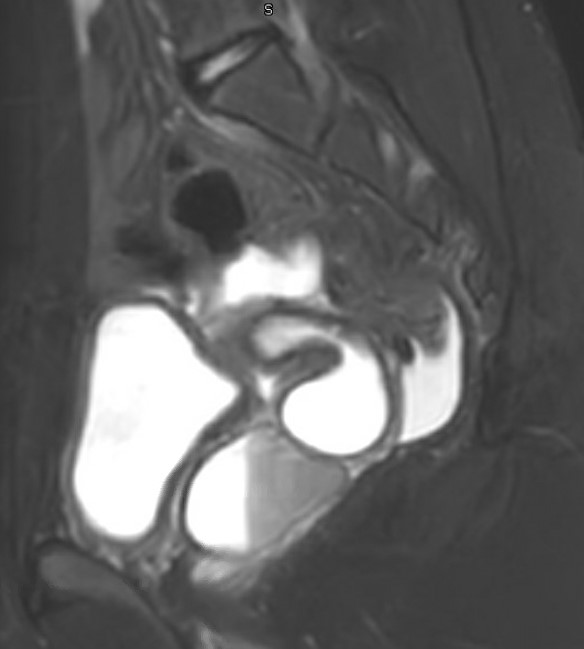

Figure 1. Sagittal view of a 2017 pelvic MRI visualizing fluid-filled distended vagina with layering debris and blood. The uterus is not visualized in this image.

When the patient began experiencing vaginal bleeding 3 days prior to presenting at our ED, the family was naturally confused, as they had been told that because of her diagnosis, the patient would never be able to menstruate or bear children. For this reason, the patient’s mother brought her to the ED for further evaluation given her complex history. Pelvic ultrasonography was conducted and revealed findings quite different from the previous MRI 4 years earlier. This ultrasonography did, in fact, show the presence of a uterus, albeit with abnormal anatomy—either bicornuate or didelphys, as well as the presence of both ovaries. The vagina was also present but was found to be distended with a blood-fluid level, a finding consistent with hematometrocolpos.

Diagnostic testing. A radiologist was consulted. Given these new ultrasonographic findings compared with the previous MRI, it was felt that her anatomy was more in line with a diagnosis of obstructed hemivagina with ipsilateral renal agenesis (OHVIRA) syndrome, a rare congenital malformation that is estimated to occur in 0.1% to 3.8% of women.1 A general surgeon was also consulted, who recommended admitting the patient to the hospital for a pelvic MRI scan with possible surgical intervention. An MRI scan was conducted the following day to assess the need for intervention, results of which confirmed the presence of a didelphys uterus with obstructed left hemivagina and left hematometrocolpos, consistent with the diagnosis of OHVIRA syndrome (Figures 2 and 3). The patient was subsequently referred to a pediatric gynecologist for surgical intervention.

Figure 2. Axial image of a 2021 pelvic MRI showing 2 distinct hemivaginas. The left hemivagina is obstructed and measures (4.3 × 4.3 × 3.6 cm), and the right hemivagina is visualized. The internal fluid level is consistent with hematometrocolpos.

Figure 3. Sagittal view of a 2021 pelvic MRI. An increase in vaginal distension with fluid level is noted, and a didelphys uterus is visualized.

Discussion. There are a variety of well-known anomalies of the female reproductive tract. One of the most common is Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, an anomaly caused by a lack of development of the Müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts. The 2 Müllerian ducts typically start to form around the fifth or sixth weeks of gestation. In normal development, these ducts are guided caudally by the Wolffian (mesonephric ducts) to the urogenital sinus. The caudal end of the 2 Mullerian ducts fuse to form the uterus, cervix, and upper vagina, and the cephalic ends form the fallopian tubes. In MRKH syndrome, these Müllerian ducts either fail to make this migration or fail to develop entirely, leaving the embryo without a uterus or upper vagina.1 While this diagnosis can be made at any point in a woman’s life, it is most often discovered when an adolescent presents with primary amenorrhea. A diagnosis of MRKH syndrome comes with significant implications, both in the physical and psychological sense, as it leads to absolute uterine factor infertility2 as well as difficulties with the ability to engage in sexual intercourse, depending on the degree of aplasia of the upper vagina. The prevalence of MRKH is not entirely established, but it is estimated to be about 1 in 5000 female patients.3

The patient underwent initial imaging studies in 2017. When her parents were told about her diagnosis of MRKH syndrome, they were naturally devastated by the prospect of their child's inability to bear children of her own, should she so choose. Given the patient’s young age at the time of diagnosis, her parents decided not to tell her about her condition until she was an adolescent and could better understand its implications. For 4 years, her diagnosis remained a secret to her, shared only among her parents and health care providers. She was only made aware of her condition the night before arriving at the ED, as her parents wanted her to understand their concern and confusion over what appeared to be a menstrual period.

While a diagnosis of OHVIRA syndrome has its own share of health consequences, including increased risk of endometriosis, pelvic abscesses, and adhesions,4 absolute uterine infertility is not one of them. In fact, early diagnosis of OHVIRA syndrome with removal of the obstructing vaginal septum allows preserved fertility in most affected patients.3 This misdiagnosis caused years of strife within the patient’s family that could have potentially been prevented. It has been established that before puberty, the uterus is generally small and underdeveloped because of the absence of hormonal stimulation, making it harder to evaluate on imaging.5,6 As the individual progresses through puberty and the reproductive organs grow to their adult size and form, they are much easier to identify and measure on imaging studies, including ultrasonography and MRI.

Conclusion. This case highlights the importance of caution when making such definitive diagnoses in preadolescents without fully developed reproductive organs, as it can lead to undue stress and trauma for the patient and his or her family.

1. Yang M, Wen S, Liu Z, et al. Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA): Early diagnosis, treatment and outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;261:12-16. doi.10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.03.018

2. Herlin MK, Petersen MB, Brännström M. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome: a comprehensive update. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):214. doi.10.1186/s13023-020-01491-9

3. Tugues M, Nunez B, Corripio R. Vaginal bleeding in a misdiagnosed Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2021;14:e241387. doi.10.1136/bcr-2020-241387

4. Jha S, Abdi S. Diverse presentations of OHVIRA syndrome: a case series. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2021;60(1):6-8. doi.10.1177/0009922820953582

5. Thewjitcharoen Y, Veerasomboonsin V, Nakasatien S, Krittiyawong S, Himathongkam T. Misdiagnosis of Mullerian agenesis in a patient with 46, XX gonadal dysgenesis: a missed opportunity for prevention of osteoporosis. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2019;19-0122. doi.10.1530/EDM-19-0122

6. Rivas AG, Epelman M, Ellsworth PI, Podberesky DJ, Gould SW. Magnetic resonance imaging of Müllerian anomalies in girls: concepts and controversies. Pediatr Radiol. 2021;52(2):200-216. doi.10.1007/s00247-021-05089-6