Epistaxis Caused by Malignant Melanoma of the Nasal Cavity: A Rarity on the Rise

Introduction. A 67-year-old woman presented to the otolaryngologist’s office with a 2-week history of recurrent epistaxis and nasal airway obstruction limited to the right nasal passage.

History. The patient had initially attempted to control the bleeding by either squeezing the lower third of her nose or inserting a cotton ball within the right nasal passage and then compressing the lower third of the nose for several minutes. Repeat attempts to control the bleeding proved ineffective. She denied any history of bleeding diathesis, hypertension, recent nasal trauma/surgical procedure, cocaine use, antecedent or concurrent nasal/sinus infection, use of nasal sprays, anticoagulants, smoking or ethanol use.

Routine and endoscopic examination of the nose revealed the presence of mild bleeding emanating from an approximately 9.0 mm x 5.0 mm polypoid lesion located on the anterior superior nasal septum. No other bleeding sites were identified. The color of the polypod lesion was no different from that of the surrounding nasal mucosa.

Diagnostic Testing. CT imaging of the nose/paranasal sinuses was obtained and failed to identify any other intranasal, nasopharyngeal, or sinus pathology aside from that of the polypoid lesion detailed above.

Differential Diagnoses. The differential diagnosis includes common causes of epistaxis, including nasal mucosal trauma/dryness, vascular malformation, granulomatous diseases, and a benign or malignant neoplasm. Each differential diagnosis was ruled out based on the patient’s clinical examination and pathology findings.

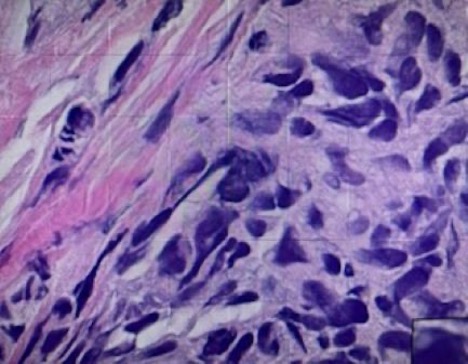

Treatment and Management. The lesion was excised in its entirety and sent for pathology (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical stains showed tumor cells positive for S100, Sox10, and HMB45 and negative for pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) supporting the diagnosis of malignant melanoma.

Fig. 1. Sections of the resected intranasal lesion reveal neoplastic cells with cytologic atypia, pleomorphism, and increased mitotic activity, consistent with malignant melanoma. Immunohistochemistry shows the tumor cells to be positive with HMB45, S100, and SOX 10, and negative for AEL/AE3 confirming the diagnosis of melanoma.

Outcome and Follow-up. The patient was referred to a regional cancer center and subsequently underwent surgical resection (septectomy) followed by adjuvant radiotherapy.

Discussion. Epistaxis (nasal bleeding) is a relatively common occurrence affecting approximately 60% of those residing in the United States. Although often self-limiting in nature, 6% of those experiencing epistaxis ultimately seek medical care. Epistaxis accounts for roughly one in 200 visits to the emergency department throughout the United States. A bimodal age-related distribution has long been recognized with an increase in epistaxis occurring during childhood and mid-to-late adulthood1-3.

A highly diverse group of clinical conditions has been identified that may either facilitate or directly effectuate the onset of nasal bleeding, including systemic diseases, bleeding disorders, nasal/facial trauma, neoplasms of the nose, nasopharynx, and paranasal sinuses, and relatively recent nasal/sinus procedures (Table 1).

Table 1. Epistaxis: Causal relationships

Clinical condition | Symptoms |

Nasal mucosa | mucosal dryness, atrophic rhinitis, digital trauma (nasal picking), postsurgical, intranasal drug use, intranasal antihistamine/steroid sprays, nasal trauma, foreign body |

Inflammatory | rhinitis (atrophic, allergic), viral/bacterial/fungal sinusitis granulomatous diseases, pyogenic granuloma |

Structural deformities | nasal septal deformities/perforations, Intranasal mucosal adhesions |

Neoplasms | vascular malformations, hemangiomas, polyps, papillomas, angiofibromas, Thorwald cyst, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, lymphoma, squamous cell carcinomas |

Coagulopathies | hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias, Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, Von Willebrand disease, hemophilia, acquired coagulopathies resulting from liver or renal disease, anti-coagulants, platelet disorders |

Although neoplasms of the nose and adjoining areas are often not associated with nasal bleeding, both benign and malignant neoplasms originating in either the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, or paranasal sinuses (collectively referred to as the sinonasal tract) should be considered as potential causes of epistaxis. In a retrospective cohort study of patients presenting with epistaxis to a regional medical center over an 11-year period, Toomey et al noted that 3.09% of these patients were discovered to have a nasal mass, of which 0.43% were malignant4. The occurrence of melanoma in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses has been increasing in number, most notably amongst those in their fifth to eighth decades of life5. In a cross-sectional analysis of 981 cases of malignant nasal cavity tumors, Bhattacharyya found that 12.1% were melanomas6.

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma has been steadily rising, often outdistancing that of other malignancies7. Primary malignant melanoma is not exclusively limited to cutaneous sites and has been found to occur in numerous unexpected locations including the nose, paranasal sinuses, trachea, bronchus, larynx, and others8. Although having long been deemed a rarity and constituting less than 1% of all melanoma cases8, an upswing in numbers of primary mucosal melanomas of the head and neck has been recognized as well. Between 15% to 33% of all cutaneous melanomas occur in the head and neck, with approximately 4% involving the sinonasal tract9.

Malignant mucosal melanoma of the sinonasal tract (MMSNT) is a rare aggressive neoplasm with a high rate of recurrence and poor prognosis. An accurate diagnosis is oftentimes delayed due to the non-specificity of presenting symptoms and possible heterogeneity of both physical findings and histopathological features. Unilateral epistaxis and nasal obstruction are the two most encountered complaints11 and often invoke little or no concern or suspicion due to their non-specificity, common occurrence, and frequent association with benign inflammatory or infectious disorders6,11. With mucosal melanomas of the sinonasal tract increasing in number, early recognition and immediate investigation are of critical importance considering the high rate of metastasis and often devastating outcomes. Recurrence rates commonly surpass that of 50% with a survival rate of less than 30%. The incidence rate of malignant melanoma of the nasoseptal tract in the United States is approximately 0.05 per 100,0005.

The nasal cavity is the most ubiquitous site of origination in MMSNT occurring in approximately 70% of cases followed thereafter by the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses5,11,12. The nasal septum and lateral wall of the nasal cavity are common sites of involvement accounting for 24.1% and 41.4%, respectively9,10. Mucosal melanomas have been found to occur in equal numbers among men and women5,11 with some reporting a slight preponderance among women5,9,12. These tumors occur most often in the fifth to eighth decades of life with a median age of 70 years5. Treatment commonly includes wide surgical excision and adjuvant radiation therapy11,12. MMSNT may prove to be histologically bewildering having at times been confused with lymphomas, plasmacytomas, Ewing Sarcomas, poorly differentiated carcinomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, neuroendocrine tumors, olfactory neuroblastomas, and others5,10,11. A timely and accurate diagnosis often necessitates the appropriate use of immunohistochemistry stains.

Described as a “great imitator histologically10,” histopathological heterogeneity is commonly encountered in cases of MMSNT. Histopathologic findings deemed to be of diagnostic value include the presence of melanin, prominent nucleoli, high rate of mitosis, and intraepithelial melanocytic proliferation5. The presence of melanin is helpful in arriving at a diagnosis, but melanin may be lacking in 30-70% of cases.5 Melanin producing melanocytes are dendritic cells that arise from neural crest tissue and are dispersed within the upper respiratory tract and oral cavity. Located at the dermo-epidermal junction of mucous membranes, melanocytes occur in significantly higher numbers in the nose (over 50%) and paranasal sinuses (20%)9,11.,

Symptoms relating to malignant melanoma of the sinonasal tract are typically nonspecific with epistaxis and nasal obstruction being the most common presenting manifestations. Other symptoms found to occur in these cases depend upon site of involvement and include facial pain, headache, hyposmia/anosmia, diplopia, proptosis, and neurological symptoms5. Some have speculated that the upswing in reported cases of mucosal melanoma may, in part, be due to updated immunohistochemical panels10,11 and improved detection rates provided by an increase in present-day use of endoscopic examination and imaging studies when compared to that of earlier years5,11.

Risk factors for cutaneous melanomas include family history, sun exposure, and benign or atypical nevi. Salari et al5 note that melanocytes in nasal and sinus mucosa may prove to be precursors and make note of a possible link between inhaled environmental elements as well as immune factors. Additional risk factors discussed in the literature include inhalation of either formaldehyde or tobacco, nasal/sinus melanosis, and African or Japanese ancestry5,11,12.

Because MMSNT lesions may vary in appearance (ulcerated, polypoid, bulky), color (melanotic or amelanotic), and histopathology (pleomorphic cell types: undifferentiated, epithelioid, small cell, etc.), a conclusive diagnosis will ultimately depend upon the use of select immunohistochemistry agents such as s-100 protein, tyrosinase, HMB-45, and others5,11. Not to be overlooked is the exceedingly rare instance of cutaneous melanoma metastasizing to the sinonasal tract, a rare occurrence found to occur in less than 1% of patients13.

Conclusion. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the sinonasal tract is a rare aggressive neoplasm with a high recurrence rate and poor prognosis. Diagnosis is often delayed or misconstrued due to the non-specificity of presenting symptoms and possible heterogeneity of both physical findings and histopathological features. Epistaxis and nasal obstruction are commonly encountered and when present, may invoke little or no concern or suspicion due to their common occurrence and frequent association with benign inflammatory or infectious disorders. With mucosal melanomas of the sinonasal tract increasing in number, early recognition and immediate investigation are needed to help lessen mortality rates. Elderly patients presenting with the commonly encountered complaints of unilateral epistaxis, unilateral nasal obstruction, or other sinonasal symptoms should not be casually dismissed without appropriate investigation. Although rare, malignant melanoma of the sinonasal tract is on the upswing and given its poor prognosis, early diagnosis increases the possibility of an improved outcome.

AUTHORS:

Sheldon P. Hersh, MD1 • Sheldon Gorbacz, MD2

AFFILIATIONS:

1Department of Otolaryngology, Lenox Hill Hospital/Northwell Health, New York, New York

2Sunrise Medical Laboratory, Hicksville, New York

CITATION:

Hersh SP, Gorbacz S. Epistaxis caused by malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity: A rarity on the rise. Consultant. Published online March 18, 2025. doi:XX

Received September 23, 2024. Accepted December 20, 2024.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

None.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Sheldon P. Hersh, MD, Lenox Hill Hospital, 100 E. 77 St. New York, New York. (sphersh.ent@gmail.com)

References

- Tunkel DE, Anne S, Payne SC, et al. Clinical practice guideline: nosebleed (epistaxis). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162:S1– S38. doi:10.1177/0194599819890327

- Yan F, Patel HP, Isaacson G. Age Distribution of Epistaxis in Outpatient Pediatric Patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023;0(0). doi:10.1177/01455613231207291

- Bui R, Doan N, Chaaban MR. Epidemiologic and Outcome Analysis of Epistaxis in a Tertiary Care Center Emergency Department. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2020;34(1):100-107. doi:10.1177/1945892419876740

- Toomey N, Hassanzadeh T, Danis DO, Tracy J. Incidence of Neoplasm in Patients Referred for Epistaxis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2024;0(0). doi:10.1177/01455613231223946.

- Salari B, Foreman RK, Emerick KS, Lawrence DP, Duncan LM. Sinonasal mucosal melanoma: an update and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022 Jun;44(6):424-432. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002157

- Bhattacharyya N. Cancer of the nasal cavity: survival and factors influencing prognosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(9):1079-83. doi:10.1001/archotol.128.9.1079

- Houghton AN, Polsky D. Focus on melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(4):275-8. doi:10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00161-7

- Cove H. Melanosis, melanocytic hyperlasia, and primary malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity. Cancer. 1979;44(4):1424-33. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1424::aid-cncr2820440438>3.0.co;2-l

- Yu H, Liu G. Clinical analysis of 29 cases of nasal mucosal malignant melanoma. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(2):1166-1170. doi:10.3892/ol.2015.3259

- Thompson LD, Wieneke JA, Miettinen M. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal melanomas: a clinicopathologic study of 115 cases with a proposed staging system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):594-611. doi:10.1097/00000478-200305000-00004

- Gilain L, Houette A, Montalban A, Mom T, Saroul N. Mucosal melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014;131(6):365-369. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2013.11.004

- Marcus DM, Marcus RP, Prabhu RS, et al. Rising incidence of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck in the United States. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:231693. doi:10.1155/2012/231693

- Billings KR, Wang MB, Sercarz JA, Fu YS. Clinical and Pathologic Distinction between Primary and Metastatic Mucosal Melanoma of the Head and Neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112(6):700-706. doi:10.1016/S0194-59989570179-6