Peer Reviewed

Diaphragmatic Hernia

Authors:

Danielle Massarella, MD

Postgraduate Year 5 Resident, Pediatrics Department, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio

David Effron, MD

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio; Attending Physician, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio

Citation:

Massarella D, Effron D. Diaphragmatic hernia [published online November 8, 2017]. Consultant360.

A 9-month-old girl was brought to her pediatrician’s office for follow-up of right lower-lobe pneumonia, which had been incidentally diagnosed the week prior when she had presented to an outside emergency department after a choking episode at home.

She had been in her regular state of health without fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, or feeding difficulties. Physical examination findings were unremarkable. There were no concerns regarding her growth and development, and her medical, surgical, and family histories were unremarkable.

Prenatal anatomic surveys had noted a normal diaphragm and chest wall, normal positioning of the stomach, and normal amniotic fluid volumes. Her immunizations were up-to-date. Repeated imaging of the chest done at the follow-up appointment was free of infiltrate or consolidation. However, a chest mass was identified, and urgent admission was arranged for further workup (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Lateral radiograph demonstrating a right-sided chest mass.

Figure 2. Posteroanterior radiograph demonstrating a right-sided chest mass.

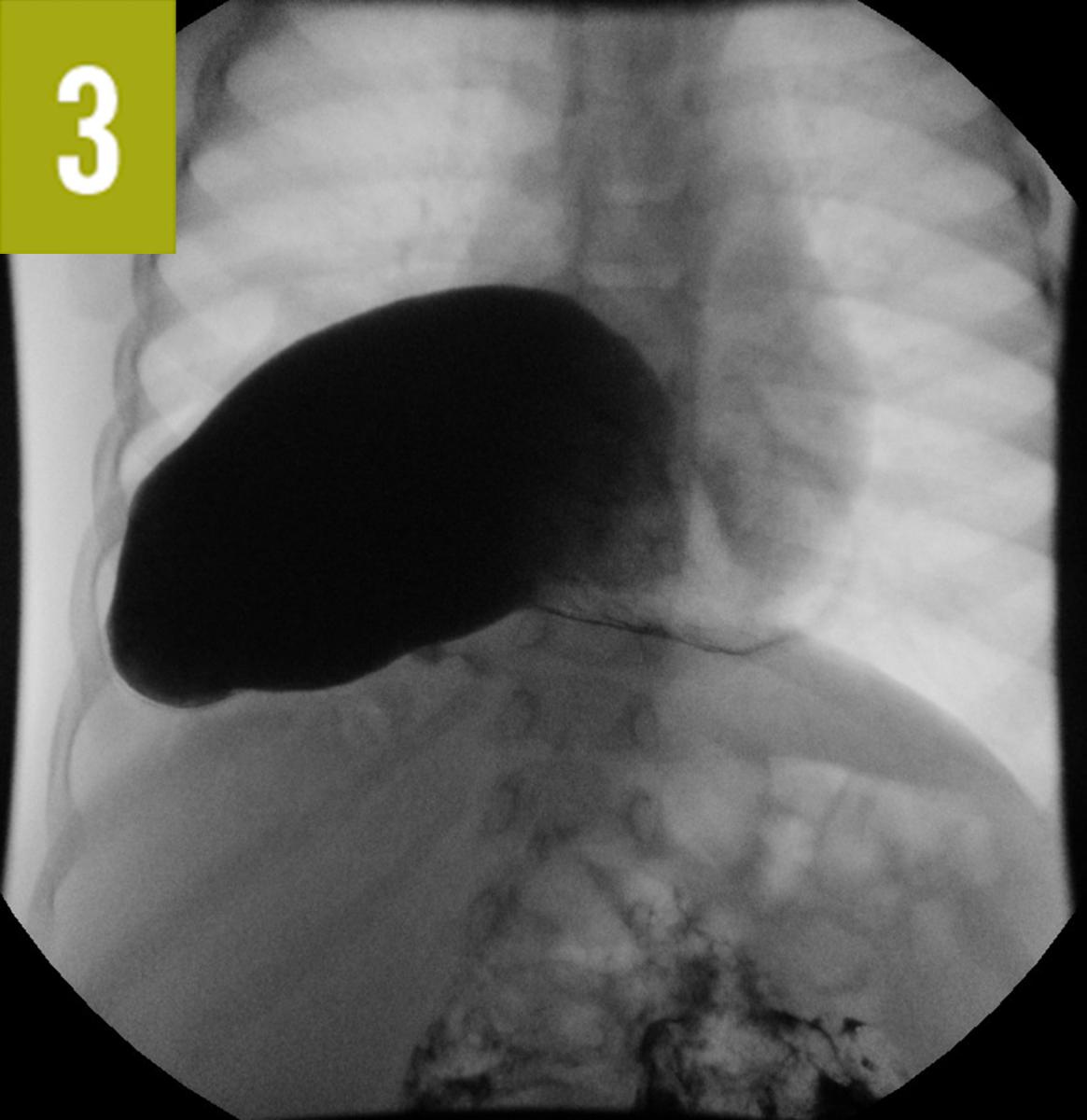

Hospital course. The patient remained stable throughout the course of the hospital stay. Subsequent imaging studies, including computed tomography and an upper gastrointestinal tract series of radiographs, showed a hiatal hernia containing the stomach and colon (Figure 3). Anterior displacement and distal narrowing of the inferior vena cava due to mass effect was noted. The gastroduodenal artery was also noted to be herniating through the defect. The lungs were unremarkable, aside from right lower-lobe atelectasis.

Figure 3. Upper gastrointestinal tract radiograph demonstrating the hiatal hernia.

Intraoperatively, the findings were further characterized as a right-sided paraesophageal hernia sac containing the entire stomach in torsion and the transverse colon. Surgical reduction and Nissen fundoplication were well tolerated.

Discussion. The prevalence of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is as high as 1 in 3000 live births.1 More than half of cases are diagnosed prenatally, when abdominal contents are noted in the thoracic cavity during routine fetal ultrasonography. Neonatal presentation is typically characterized by mild to severe respiratory distress, given the strong association between CDH and pulmonary hypoplasia.2 The 5% to 10% of patients presenting after infancy may experience chronic or acute respiratory and gastrointestinal tract symptoms, which prompt the diagnostic workup. Only 1% of cases are discovered incidentally as in our patient’s case. Furthermore, paraesophageal hernia is a rare condition in infancy; the majority of congenital diaphragmatic defects are of either the Bochdalek (80%-90%) or the Morgagni (2%) types.1 The incidence and prevalence of gastric volvulus in association with CDH are unknown.2

- Pober BR, Russell MK, Ackerman KG. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1359. Updated March 16, 2010. Accessed November 6, 2017.

- Jeyarajah DR, Harford WV Jr. Abdominal hernias and gastric volvulus. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. Vol 1. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:379-395.