Woman With Cough and Dyspnea

A 51-year-old woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presents with nonproductive cough and slowly progressive dyspnea of 3 months' duration. She denies fever, chills, and night sweats. Over the past 3 months, she has received several different courses of treatment; the latest was cefixime, a 2-week tapering dose of prednisone, and bronchodilators. These treatments have failed to alleviate her symptoms.

The patient has chronic back pain that resulted from injuries she sustained in a motor vehicle accident and chronic constipation from long-term use of narcotic analgesics. She also has seasonal allergies and a 25 pack-year history of smoking. Her medications include oxycodone/acetaminophen, mineral oil, garlic tablets, and an ipratropium inhaler.

Vital signs are normal. Hyperresonance to percussion and a prolonged expiratory phase of respiration are noted. Breath sounds are decreased, and egophony is heard at the mid left posterior lung field. Other examination findings are unremarkable.

Vital signs are normal. Hyperresonance to percussion and a prolonged expiratory phase of respiration are noted. Breath sounds are decreased, and egophony is heard at the mid left posterior lung field. Other examination findings are unremarkable.

Results of a tuberculin skin test are negative. The white blood cell count, with differential, and hematocrit are normal.

Arterial blood gas measurements on room air show a pH of 7.42; PaCO2, 36 mm Hg; and PaO2, 71 mm Hg, with saturations of 95%. Spirometry demonstrates a mild obstructive ventilatory defect, with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1):forced vital capacity ratio of 66% and FEV1 of 2.38 L (83% of predicted). The carbon monoxide-diffusing capacity is preserved.

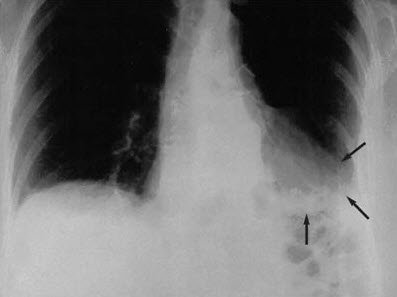

The posteroanterior chest radiograph shows an irregular spiculated mass, airspace disease, and volume loss that involves the left lower lobe with a pleural reaction. The cardiac and mediastinal configuration is unremarkable; right convex thoracic scoliosis is apparent (Figure 1). The chest CT scan (mediastinal window) shows irregular-appearing airspace disease; however, the center of the lesion has low attenuation, between 240 and 260 Hounsfield units (HU), which suggests the presence of fat (Figure 2). Bronchoscopy is nondiagnostic. A bronchogenic tumor is suspected based on the patient's history and the abnormal CT findings.

The posteroanterior chest radiograph shows an irregular spiculated mass, airspace disease, and volume loss that involves the left lower lobe with a pleural reaction. The cardiac and mediastinal configuration is unremarkable; right convex thoracic scoliosis is apparent (Figure 1). The chest CT scan (mediastinal window) shows irregular-appearing airspace disease; however, the center of the lesion has low attenuation, between 240 and 260 Hounsfield units (HU), which suggests the presence of fat (Figure 2). Bronchoscopy is nondiagnostic. A bronchogenic tumor is suspected based on the patient's history and the abnormal CT findings.

A left lower lobectomy is performed. Exogenous sections from the left lower lobe specimen show an increased number of macrophages and lipid-laden macrophages ("lipophages"). Some histiocytes show fine vacuoles; others form multinucleated foreign-body giant cells. Chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and a variable amount of fibrosis are apparent in other areas. There is no evidence of malignancy (Figure 3). These findings, along with the patient's use of mineral oil, confirm the diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia.

A left lower lobectomy is performed. Exogenous sections from the left lower lobe specimen show an increased number of macrophages and lipid-laden macrophages ("lipophages"). Some histiocytes show fine vacuoles; others form multinucleated foreign-body giant cells. Chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and a variable amount of fibrosis are apparent in other areas. There is no evidence of malignancy (Figure 3). These findings, along with the patient's use of mineral oil, confirm the diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia.

The patient's recovery is uneventful, and she is discharged 6 days after surgery.

LIPOID PNEUMONIA: AN OVERVIEW

Since it was first described in 1925, lipoid pneumonia has become less common because of the decreased use of oil-based and lipid-based medications, particularly constipation remedies (eg, caster oil and mineral oil). This inflammatory, granulomatous, fibrotic reaction of the lung is a response to the aspiration of mineral, animal, or vegetable oil products.1

Lipoid pneumonia is referred to as the "golden pneumonia" because of its histologic appearance. The color results from the filling of alveoli with foamy macrophages that are packed with small lipid droplets and cellular debris.

The precise mechanism of oil-induced damage to the lung is unknown. Because of its high viscosity, mineral oil depresses the cough reflex and facilitates aspiration, even in patients without dysphagia. In one series, 25% of cases of lipoid pneumonia occurred in healthy persons without predisposing risk factors, such as cerebrovascular accidents, neuromuscular disorders, developmental delay, Parkinson disease, and Alzheimer disease.2

Once the lipids reach the lung, they are emulsified and phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. The macrophages release inflammatory cytokines that recruit neutrophils to the area. These inflammatory cells secrete proteases and oxygen radicals that augment the inflammatory reaction. Lung lipases also contribute to the foreign-body inflammatory reaction.2 These cellular responses--along with impaired mucociliary transport, poor secretion clearance, and chronic inflammation--result in structural airway damage.

CAUSES

Lipoid pneumonia has been associated with the aspiration of exogenous materials, such as high-fat milk in infants, cod liver oil, lip gloss,3 and oil-based nose drops. In children, repeated use of oil-based cathartics is the cause of most lipoid pneumonias. In this patient, the garlic tablets, which have an oil base, and mineral oil were the likely exogenous sources. Lipoid pneumonia may also be caused by endogenous lipids, most often in association with airway obstruction by bronchial tumors, such as squamous cell and large-cell carcinomas.4

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical features. Consider lipoid pneumonia in patients with nonresolving pneumonia. Symptoms include dyspnea, cough, mucus production, and chest pain, although about half of patients with lipoid pneumonia are asymptomatic.

Ask patients about over-the-counter medications, home-based remedies, and nutritional supplements. A careful history taking is the key to successful diagnosis.

Although any area of the lung may be affected, lipoid pneumonia is typically unilateral and involves dependent lung regions.5 Bronchiectasis and cor pulmonale can result from long-term ingestion.

Diagnostic studies. Lipoid pneumonia usually appears as a solitary mass and can be mistaken for a tumor, as in this case. When lipoid pneumonia occurs as diffuse parenchymal lung disease, it can cause ventilation-perfusion mismatch, respiratory insufficiency, and hypoxemia.

Certain radiographic findings can assist in the diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia.6-9 The most specific diagnostic finding is the quantification of the density of the consolidation via CT imaging. A negative density between 230 and 2150 HU is highly suggestive of intrapulmonary fat.9

Interlobular septal thickening, superimposed ground-glass opacities, and a "crazy-paving" pattern of interstitial thickening are also highly suggestive of lipoid pneumonia.10,11 In a retrospective study that compared pathologic diagnosis with the CT and MRI findings, lipoid pneumonia was frequently associated with the crazy-paving pattern, combined with low-attenuation values within the consolidation.12 MRI is less accurate than high-resolution CT in the diagnosis of lipoid pneumonias, because quantitative signal intensity is unmeasurable.

Although nondiagnostic in this patient, bronchoscopy findings may be helpful in the diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia.13,14 In a child with chronic lipoid pneumonia, serial bronchoalveolar lavage analysis revealed a marked reduction in the total number of normal alveolar macrophages and prominent lipid-laden macrophages at the end of 18 months. The number of eosinophils and lymphocytes was increased at diagnosis; however, only the lymphocytes expressed antigen surface markers (HLA-DR, HLA-CD54, and CD25) and remained positive at the end of 18 months.15 These lymphocyte surface antigens indicate that a major compatibility complex II response may be necessary for persistent inflammation and fibrosis.15 These findings further suggest that clearance of aspirated oil from the respiratory tract is a slow process. This delayed clearance may be responsible for the marked toxicity that intrapulmonary lipids can induce.

MANAGEMENT

Treatment of lipoid pneumonia is mainly supportive. Symptoms and radiographic abnormalities resolve within months after ingestion of oil- or fat-based products is discontinued. In patients with diffuse pulmonary damage, aggressive therapy with oral prednisone16,17 and whole lung lavage has been used.18,19