Elderly Man With Hypothermia

On a warm August day, a 79-year-old man is hospitalized because of progressive lethargy over the past week. Previously, he was alert and able to converse. He has no chest pain, dyspnea, or cough. His history includes hypertension of unknown duration, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and a recent hospitalization for pneumonia.

Blood pressure is 80/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 46 beats per minute; respiration rate, 28 breaths per minute; oxygen saturation, 96% while breathing 2.5 L of oxygen via a nasal cannula; and temperature, 31°C (88°F). Oral mucosa and skin are dry. Jugular veins are nondistended and carotid bruits are absent. S1 and S2 are distinct, without murmurs, gallops, or friction rubs. Point of maximal impulse is not displaced. Scattered rhonchi are noted over both lung bases. The abdomen is soft and nontender. There is no pedal edema.

The patient opens his eyes spontaneously on occasion and moans but does not move purposefully. He withdraws his extremities from painful stimuli. Babinski reflexes are absent.

The blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio is elevated; other laboratory results are normal. A chest radiograph shows no active disease. A CT scan of the head reveals no acute hemorrhagic or ischemic event.

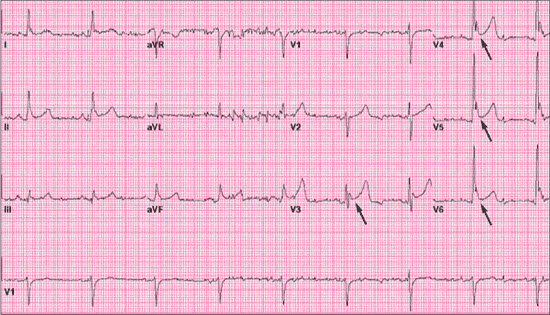

The ECG shows a prominent QRS voltage in the left precordial leads, which suggests left ventricular hypertrophy. However, on closer observation, there is an extra positive deflection between the terminal portion of the QRS complex and the beginning of the ST segment (Figure 1). These prominent deflections, most clearly visible in the precordial leads V3 to V6, are Osborn or "J" waves. They are the classic ECG finding in hypothermia. Sometimes referred to as a "camel's hump," Osborn waves probably represent intraventricular conduction delay. They are present in about 80% of patients with core temperatures of less than 35.5°C (96°F).1

The ECG shows a prominent QRS voltage in the left precordial leads, which suggests left ventricular hypertrophy. However, on closer observation, there is an extra positive deflection between the terminal portion of the QRS complex and the beginning of the ST segment (Figure 1). These prominent deflections, most clearly visible in the precordial leads V3 to V6, are Osborn or "J" waves. They are the classic ECG finding in hypothermia. Sometimes referred to as a "camel's hump," Osborn waves probably represent intraventricular conduction delay. They are present in about 80% of patients with core temperatures of less than 35.5°C (96°F).1

ECGs obtained on the second (Figure 2) and sixth (Figure 3) hospital days--after the patient's temperature rose to 33.3°C (92°F) and 35.5 (96°F), respectively--display progressive resolution of the Osborn waves. Amplitudes of Osborn waves are inversely proportional to body temperature.2

ECGs obtained on the second (Figure 2) and sixth (Figure 3) hospital days--after the patient's temperature rose to 33.3°C (92°F) and 35.5 (96°F), respectively--display progressive resolution of the Osborn waves. Amplitudes of Osborn waves are inversely proportional to body temperature.2

HYPOTHERMIA: AN OVERVIEW

HYPOTHERMIA: AN OVERVIEW

Hypothermia--defined as a core body temperature of less than 35°C (95°F)--claims about 600 lives every year in the United States.3,4 Certain populations (eg, alcoholics,drug users, elderly persons, homeless persons, chronically ill patients, and those with preexisting heart disease) are at increased risk for death from hypothermia.4

This case was interesting because it occurred in the summer. Most cases of hypothermia are caused by prolonged exposure to cold and are reported during the winter and in cold regions. Other causes of hypothermia include endocrine-related diseases, such as hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, adrenal insufficiency, and hypoglycemia; neuromuscular disease; malnutrition; drugs (notably neuroleptic and general anesthetic agents); and sepsis--which was the presumed cause in this patient. The sepsis was related to his previous hospitalization for pneumonia.

Results of a thyroid-stimulating hormone test and dexamethasone suppression test ruled out hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency; there was no documented hypoglycemia. Results of a urinalysis, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, blood and urine cultures, and chest CT scan were all unremarkable.

ECG FINDINGS IN HYPOTHERMIA

ECG features of hypothermia may vary according to the degree of core temperature decline.1 In mild hypothermia (32.2°C to 35°C [90°F to 95°F]), tachycardia may be observed secondary to sympathetic stimulation. As the core temperature approaches 28°C to 32.2°C [82.4°F to 90°F] (moderate hypothermia), sinus bradycardia, QT prolongation, junctional rhythm, atrial fibrillation with a slow ventricular response,5 T-wave abnormalities, and prolongation of the PR interval are common. Sinus bradycardia and QT prolongation may be gleaned from this patient's initial ECG (see Figure 1), as well as marked baseline interference. These rapid, intermittent signals reflected in the isoelectric line of the ECG are produced by muscle tremors from shivering. In one study, the ability to mount this shivering artifact was associated with improved survival.6

In severe hypothermia (less than 28°C [82.4°F]), asystole or ventricular fibrillation may occur. These characteristic ECG features are believed to result from slowed impulse conduction through potassium channels.

OUTCOME OF THIS CASE

Initial management included active, external rewarming with warm blankets and warm intravenous fluids. The patient was also given broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, and he was closely monitored in the ICU. His level of consciousness gradually increased as his temperature returned to normal.

1. Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung. 2001;30:161-163.

2. Patel A, Getsos JP, Moussa G, Damato AN. The Osborn wave of hypothermia in normothermic patients. Clin Cardiol. 1994;17:273-276.3. Danzl DF, Pozos RS. Accidental hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1756-1760.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypothermia-related deaths--United States, 2003. MMWR. 2004;53:172-173.

5. Mattu A, Brady WJ, Perron AD. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hypothermia. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:314-326.

6. Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001;12:232-235.