Anxiety Disorders: Guidelines for Effective Primary Care, Part 2, Treatment

AUTHOR:

Hani Raoul Khouzam, MD, MPH

VA Central California Health Care Center, Fresno

University of California, San Francisco

CITATION:

Khouzam HR. Anxiety disorders: guidelines for effective primary care, part 2, treatment. Consultant. 2009;49(4):225-238.

ABSTRACT: The presence of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions affects the management of anxiety disorders. If the presenting anxiety symptoms are secondary to a medical condition, treatment of the condition usually leads to remission of anxiety. When a comorbid psychiatric condition is present, simultaneous treatment with the anxiety disorder is recommended. The management of anxiety disorders in patients with alcohol or substance abuse disorders should be coordinated with a psychiatrist or an addiction specialist; other indications for psychiatric consultation are suicidal risk, lack of adherence, and refractory symptoms. A large body of evidence supports the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and supportive psychotherapy for anxiety disorders. Numerous pharmacological therapies are available. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally considered first-line treatment; however, consider serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants and, in some cases, benzodiazepines when patients have not responded to SSRIs or when their adverse effects exceed their benefits.

Most uncomplicated anxiety disorders can be treated in the primary care setting. Following the initial treatment, patients require ongoing care, which combines psychosocial and psychopharmacological therapies. Treatment of anxiety disorders can lead to improved interpersonal, social, and vocational functioning.

In the second part of this 2-part series, I describe the various treatments, with emphasis on those that are typically used in the primary care setting. In part 1 (CONSULTANT, March 2009, page 169), I addressed the clinical presentation, the relevant diagnostic studies, and the differential diagnosis.

TREATMENT OF ANXIETY DISORDERS AND COMORBID CONDITIONS

Sequence of treatment. The management of an anxiety disorder depends on the specific diagnosis and the presence of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions.1 If the presenting anxiety symptoms are secondary to a medical condition, treatment of the condition usually leads to remission of anxiety.1,2 Thus, comorbid medical conditions should be treated first, followed by the anxiety disorder. When a comorbid psychiatric condition is present, simultaneous treatment with the anxiety disorder is recommended.1,3,4

Comorbid substance abuse. The management of anxiety disorders in patients with alcohol or substance abuse disorders should be coordinated with a psychiatrist or an addiction specialist.3,5,6 Discuss the long-term risks of dependence, withdrawal, and abuse, as well as the intended course of treatment. In general, it is advisable to treat alcohol and substance abuse disorders before the initiation of pharmacological therapy for anxiety disorders.1-3

INITIAL PRIMARY CARE INTERVENTION

In a primary care setting, the following immediate steps can be instituted7:

- Perform an evaluation to identify a provisional diagnosis of an anxiety disorder.

- Assess the degree and the severity of personal, social, and vocational impairment.

- Educate the patient about the nature and origin of anxiety symptoms.

- Incorporate family and social support resources to encourage anxious patients to use their coping skills and problem-solving abilities.

- Suggest lifestyle changes as appropriate, including stress reduction techniques; avoidance of alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, and illicit drug use; and proper diet and regular exercise.

- Establish and maintain a therapeutic alliance that conveys a sense of understanding and empathy.

Resources for patients, including those that can provide referrals to specialists and self-help groups, are listed in the Box (at the end of this article).

WHEN TO SEEK PSYCHIATRIC CONSULTATION

An urgent psychiatric consultation for the evaluation and treatment of anxiety disorders may be necessary under the following circumstances5,6:

- There is serious risk of suicide.

- The diagnosis is uncertain.

- Psychotic symptoms are present.

- Comorbid illicit drug or alcohol use is present.

- The anxiety symptoms are chronic, severe, and disabling.

- The patient is elderly or is a child or adolescent.

- The patient refuses to adhere to the recommended treatment.

- No improvement is evident after a period of initial treatment and follow-up.

The main difficulty in referring to psychiatric services is discussing the referral with the patient. The stigma attached to mental illness continues despite medical and community education programs. As a consequence, referral needs to be handled tactfully. Discussing emotional factors and illness, explaining and demystifying psychiatric services, and addressing patient fears and beliefs about psychiatrists are key elements in the process.5,6

PSYCHOSOCIAL AND SPIRITUAL INTERVENTIONS

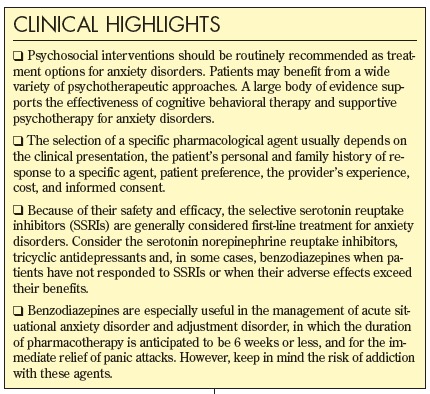

Psychosocial interventions should be routinely recommended as treatment options for anxiety disorders. Inform patients about all the available forms of treatment, including various psychotherapies. Patients may benefit from a wide variety of psychotherapeutic approaches. A large body of evidence supports the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and supportive psychotherapy for anxiety disorders.8

Cognitive behavioral therapy. The basic concepts of CBT are that thoughts cause feelings and behaviors; it relies on a collaborative effort between the psychotherapist and the patient. The patient's role is to identify goals, to express concerns, and to learn and implement learning. The psychotherapist's role is to help the patient define the goals and to listen, teach, and encourage.

CBT is based on "rational thought," which can be described in facts, not assumptions. It is structured, directive, and rooted in the notion that maladaptive behaviors are the result of skill deficits and faulty thinking. It also emphasizes that most emotional and behavioral reactions are learned. Therefore, the goal of therapy is to help patients unlearn their unwanted reactions and to learn a new way of reacting. Homework is a central feature of CBT, in which assignments on how to identify the feelings that provoke thoughts and behaviors are completed following each therapy session. It is a brief and timelimited therapy with an average of 16 sessions.9

Spiritual interventions. An assessment of the patient's religious and spiritual beliefs may allow the integration of another source of referral and support. Such referral could provide additional effective interventions, such as prayer, meditation, or Bible readings, for those patients with anxiety disorders who derive strength, endurance, and coping from their personal religious faith.10

PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT

Most pharmacological therapies for uncomplicated anxiety disorders can be initiated and monitored in the primary care setting.7 A broad range of pharmacological agents are available; these include:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

- Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

- Buspirone.

- Benzodiazepines.

The selection of a specific agent usually depends on the clinical presentation, the patient’s personal and family history of response to a specific agent, patient preference, the provider’s experience, cost, and informed consent.1,2,11,12

Because of their safety and efficacy, the SSRIs are generally considered first-line treatment for anxiety disorders.3,7 It is important to be aware of the antidepressant product labeling mandated by the FDA, which includes warnings about the increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in young adults.

Sexual side effects are associated with decreased adherence to SSRI maintenance therapy.13 Strategies to minimize these undesired effects may include using an antidepressant that is not associated with sexual side effects, switching to a different antidepressant if symptoms emerge, adding adjunctive medications to counteract side effects, and adjusting the dose and dosing schedule. A medication holiday in anticipation of sexual activity is not advisable because some reports suggest an increase in relapses occurs even with short medication holidays.3,13

The SNRIs, TCAs, and benzodiazepines may be considered when patients have not responded to SSRIs or when their adverse effects exceed their benefits.14 MAOIs are rarely used to treat anxiety in the primary care setting because of the need for strict monitoring of intake of tyramine- containing food as well as potentially serious interactions with other medications, alcohol, and illicit drugs.

Benzodiazepines are especially useful in the management of acute situational anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder, in which the duration of pharmacotherapy is anticipated to be 6 weeks or less, and for the immediate relief of panic attacks.15 The risk of addiction with benzodiazepines should be carefully considered before they are used to treat anxiety disorders. These agents should be avoided in patients with a history of alcohol or other drug abuse.1,3,15

When anxiety symptoms persist, non–FDA-approved medications may be used off-label, either as adjunctive or as primary agents. The rationale for using these medications needs to be carefully detailed and documented.15

Acknowledgments: The author thanks the VA Medical Center director, Mr Alan Perry, FACHE, for his administrative support; Drs Robert Hierholzer, Nestor Manzano, Scott Ahles, and Craig C. Campbell for their clinical guidance; Dr Avak A. Howsepian for his constructive criticism; Matthew Battista, PhD, Thomas Williams, MSW, and Leonard Williams, PA, for their encouragement; and Ms Emma Nichols for her computer assistance.

REFERENCES:

1. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Gabbard GO. Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 3rd ed. Vols 1 & 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

4. Kendrick T. Depression in adults: GPs are not so bad at diagnosis. BMJ. 2008;336:522.

5. Khouzam HR. Depression: guidelines for effective primary care, part 1, diagnosis. Consultant. 2007;47:757-764.

6. Khouzam HR. Depression: guidelines for effective primary care, part 2, treatment. Consultant. 2007;47:841-848.

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

8. Cottraux J, Note I, Yao SN, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of cognitive behavior therapy with Rogerian supportive therapy in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a 2-year follow-up. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:101-110.

9. Bodden DH, Dirksen CD, Bögels SM, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of family CBT versus individual CBT in clinically anxious children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13:543-564.

10. Baetz M, Griffin R, Bowen R, Marcoux G. Spirituality and psychiatry in Canada: psychiatric practice compared with patient expectations. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:265-271.

11. Lépine JP. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: prevalence and societal costs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 14):4-8.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1998.

13. Akpafflong MJ, Wilson-Lawson M, Kunik ME. Antidepressant-associated side effects in older adult depressed patients. Geriatrics. 2008;63:18-23.

14. Bourin M, Lambert O. Pharmacotherapy of anxious disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:383-400.

15. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Gould RA, et al. A comparison of the efficacy of clonazepam and cognitive behavioral group therapy for the treatment of social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14:345-358.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

Khouzam HR, Tan D, Gill TS. Handbook of Emergency Psychiatry. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007.

Additional Resources for Patients With Anxiety Disorders |

1. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Gabbard GO. Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 3rd ed. Vols 1 & 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

4. Kendrick T. Depression in adults: GPs are not so bad at diagnosis. BMJ. 2008;336:522.

5. Khouzam HR. Depression: guidelines for effective primary care, part 1, diagnosis. Consultant. 2007;47:757-764.

6. Khouzam HR. Depression: guidelines for effective primary care, part 2, treatment. Consultant. 2007;47:841-848.

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

8. Cottraux J, Note I, Yao SN, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of cognitive behavior therapy with Rogerian supportive therapy in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a 2-year follow-up. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:101-110.

9. Bodden DH, Dirksen CD, Bögels SM, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of family CBT versus individual CBT in clinically anxious children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13:543-564.

10. Baetz M, Griffin R, Bowen R, Marcoux G. Spirituality and psychiatry in Canada: psychiatric practice compared with patient expectations. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:265-271.

11. Lépine JP. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: prevalence and societal costs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 14):4-8.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1998.

13. Akpafflong MJ, Wilson-Lawson M, Kunik ME. Antidepressant-associated side effects in older adult depressed patients. Geriatrics. 2008;63:18-23.

14. Bourin M, Lambert O. Pharmacotherapy of anxious disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:383-400.

15. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Gould RA, et al. A comparison of the efficacy of clonazepam and cognitivebehavioral group therapy for the treatment of social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14:345-358.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

• Khouzam HR, Tan D, Gill TS. Handbook of Emergency Psychiatry. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007.