A Young Adult’s Knee Pain, Effusion, and Pyomyositis: What’s the Source?

An 18-year-old young adult presented with a 1-week history of progressive left knee pain and swelling. Three weeks before the onset of her knee pain, she had been evaluated in the emergency department for similar swelling in her right ankle. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at that time showed synovitis in her ankle without effusion or bony changes. Her ankle pain and swelling had resolved several days later with rest and anti-inflammatory use.

She had been treated for a chlamydial infection 1 year ago and reported having had no sexual activity since then. She recently had been discharged from a juvenile detention center, and she had spent time at a substance abuse and behavioral treatment program 1 year prior to the current presentation. Her family history is significant for rheumatoid arthritis in her maternal grandmother.

At presentation, she reported that she was currently menstruating, and she noted an 8-pound weight loss over the last 2 weeks. She denied a history of trauma, fever, rash, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or vaginal discharge. On physical examination, she was afebrile and generally well appearing. She had significant left knee pain with decreased range of motion, diffuse tenderness to palpation, and swelling with fluctuation. There was no erythema or significant warmth of the knee.

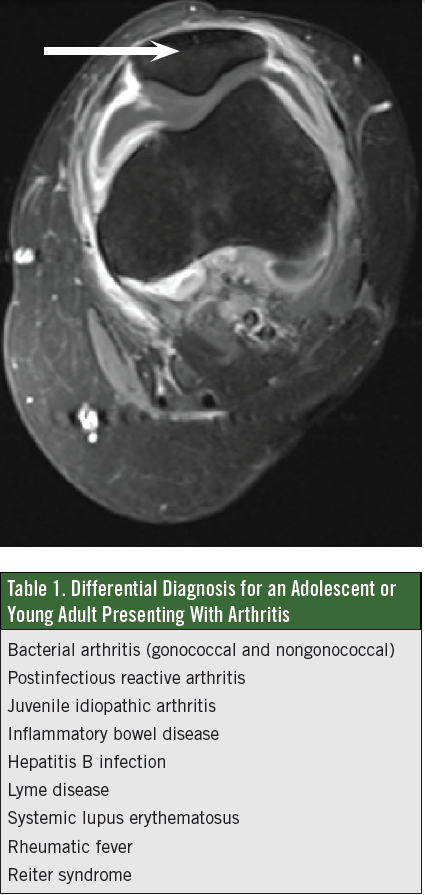

Initial laboratory test results showed a normal complete blood count, a C-reactive protein level of 6.8 mg/dL, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 104 mm/h, an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:1,280 with a speckled fluorescence pattern, and a rheumatoid factor of 640 U/mL. The lack of fever and the lack of warmth or erythema of the knee, in conjunction with her recent ankle synovitis and family history of rheumatoid arthritis, increased the concern for rheumatologic disease. A rheumatologist was consulted and an MRI obtained, the results of which showed a large joint effusion and surrounding pyomyositis (Figure).

What do this patient’s signs and symptoms indicate?

A. Disseminated gonococcal infection

B. Rheumatoid arthritis

C. Septic arthritis

D. Lyme disease

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: A, disseminated gonococcal infection

A blood culture was obtained, and wound cultures were obtained upon surgical drainage of her muscle and joint abscesses. Synovial fluid showed a white blood cell count of 71,893/µL with 97% polymorphonuclear cells and 3% monocytes. She received an initial diagnosis of septic arthritis and was started on a regimen of clindamycin postoperatively.

On postoperative day 2, the patient became febrile with worsening knee pain; her synovial culture grew Neisseria gonorrhoeae. With a refined diagnosis of disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), her antibiotic regimen was changed to ceftriaxone, and she also received 1 dose of azithromycin for a positive chlamydia result on a urine test done at the time of admission. She completed 7 days of antibiotic therapy with a change from ceftriaxone to an oral third-generation cephalosporin after clinical improvement.

On postoperative day 2, the patient became febrile with worsening knee pain; her synovial culture grew Neisseria gonorrhoeae. With a refined diagnosis of disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), her antibiotic regimen was changed to ceftriaxone, and she also received 1 dose of azithromycin for a positive chlamydia result on a urine test done at the time of admission. She completed 7 days of antibiotic therapy with a change from ceftriaxone to an oral third-generation cephalosporin after clinical improvement.

Although DGI typically is an acute presentation of infection, the patient continued to deny having had sexual activity in more than a year. At the time of discharge, she had marked improvement in joint mobility with near full ability to ambulate without pain.

The patient continued to follow up with rheumatology after resolution of her DGI, and her laboratory test results continued to be abnormal. The arthritis in her knee returned, with subsequent MRIs suggestive of chronic arthritis. She has since received a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) for which she is undergoing treatment.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for adolescents and young adults presenting with arthritis is broad (Table 1), and the diagnosis can be difficult to make due to social and clinical factors obscuring the etiology. Since N gonorrhoeae is the sexually transmitted bacteria that most often causes infective arthritis, this pathogen should be strongly considered in sexually active patients with arthritis.1

Gonorrhea is the second most common sexually transmitted disease in the United States, with an annual incidence of approximately 700,000 cases.6 The most common manifestations of N gonorrhoeae infection in adolescents and young adults are urethritis, proctitis, cervicitis, pharyngitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and DGI.

DGI has been reported to occur in 0.5% to 3% of patients with N gonorrhoeae infection. DGI is more than 4 times more common in the female population than in the male population, and females have an increased risk of DGI during menstruation or pregnancy as a result of changes in genital flora, vaginal pH, cervical mucus, and the introduction of endometrial submucosal vessels to the organism.1

DGI is classified as tenosynovitis-dermatitis syndrome or suppurative arthritis. These stages often can be linked, with unrecognized and untreated tenosynovitis-dermatitis syndrome progressing to suppurative arthritis. Tenosynovitis-dermatitis syndrome consists of inflammation of one or more tendon sheaths, polyarthralgia, and a rash. The rash typically comprises small papules or pustules that may be few in number and may go unnoticed by the patient and an examining clinician. During the acute stage, fever often is present, although it may be brief, and patients with suppurative arthritis often are afebrile at presentation.

The arthritis of DGI most is often monoarticular in weight-bearing joints, and synovial fluid cell counts are similar to those seen in patients with arthritis caused by other bacterial pathogens. Synovial fluid culture reveals the organism in approximately 50% of cases; the identification of the pathogen can be improved by using polymerase chain reaction to detect N gonorrhoeae DNA, in addition to bacterial culture.1,2

The current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention treatment recommendation for DGI is intravenous or intramuscular ceftriaxone every 24 hours, continued for 24 to 48 hours after clinical improvement is noted, at which time therapy can be changed to oral cefixime twice daily, to complete at least 7 days of therapy.6

If the gonococcal infection is complicated by meningitis, septic arthritis, or endocarditis, a longer antimicrobial treatment course should be considered. Given the frequency of coinfection, patients with DGI also should receive empiric treatment for presumed concurrent Chlamydia trachomatis infection with either azithromycin in a single dose or doxycycline for 7 days.6

Differentiating among the possible causes of arthritis in adolescents and young adults at initial presentation can be challenging (Table 2), and individuals with preexisting inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis have an increased risk for developing septic arthritis.3

Although they are suggestive of rheumatologic disease, the levels of autoantibodies used in the diagnosis of rheumatologic disease also can be a reflection of systemic inflammation from acute infection; therefore, further evaluation typically should be deferred until resolution of the infection.

SLE was diagnosed in our patient upon resolution of her DGI; often, patients with SLE or rheumatoid arthritis present with worsening monoarticular joint disease and have a delayed diagnosis of bacterial arthritis. The reported incidence of gonococcal infections in persons with SLE is higher than in the general population.4,5 The mechanisms for the increased susceptibility to N gonorrhoeae in patients with SLE are a general dysfunction of the mononuclear phagocyte system and relative hypocomplementemia, similar to the susceptibility known to affect patients with congenital complement deficiencies. Given that the rates of DGI and gonococcal arthritis are decreasing in the general population, it has been proposed that patients with DGI should be tested for hypocomplementemia and rheumatologic disease.4,5

Joanne Lane, DO, is a third-year pediatrics resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia.

Rianna Leazer, MD, is an attending physician at Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia.

References

1. Rice PA. Gonococcal arthritis (disseminated gonococcal infection). Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(4):853-861.

2. Angulo JM, Espinoza LR. Gonococcal arthritis. Compr Ther. 1999;25(3):155-162.

3. Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, Bent S. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007;297(13):1478-1488.

4. Mitchell SR, Nguyen PQ, Katz P. Increased risk of neisserial infections in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1990;20(3):174-184.

5. Vaughan KD, Aquart AM. Systemic lupus erythematosus and Neisseria gonorrhoea: a case of the arthritis-dermatitis syndrome. West Indian Med J. 2011;60(6):688-689.

6. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.