What’s the Cause of This Girl’s Widespread Papulovesicular Rash?

A 13-year-old girl presented with a 2-week history of a new-onset erythematous vesicular eruption on her right palm. The rash had been diagnosed clinically as a herpes simplex virus 1 infection by an outside physician and had been treated with acyclovir. Despite the antiviral medication, the lesions continued to spread. One week later, the rash became intensely pruritic and progressed to complete desquamation of the palm (Figure 1). She received a new diagnosis of fungal infection, and treatment with itraconazole was initiated in place of acyclovir.

Two days later, a widespread, symmetric, papulovesicular rash appeared over her forehead, nose, ears, torso, bilateral upper and lower extremities, palms, and soles (Figures 2-4). She was admitted to our hospital with concern for a possible drug-induced reaction.

Physical examination revealed an otherwise healthy adolescent in no acute distress. The patient’s past medical history was unremarkable, but she has a strong family history of atopy. There were no known exposures to chemicals or to persons with similar skin lesions. However, the patient’s mother reported that a pet hedgehog had been purchased 3 months previously.

What explains this girl’s dermatologic symptoms?

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: Id reaction secondary to atopic dermatitis

Skin scrapings from the girl’s right palm were sent for analysis. Results of a potassium hydroxide skin preparation were negative for fungal infection. Histopathologic analysis was consistent with spongiotic dermatitis, and infection with Staphylococcus aureus later was evident on culture from these samples. She received a diagnosis of atopic dermatitis with id reaction.

Oral antihistamines and wet compresses were used to treat the pruritic lesions. A 2-week course of mupirocin applied to the right palm led to complete resolution of symptoms. During this time, she was instructed to avoid contact with the hedgehog.

Autoeczematization, or id reaction, is particularly common in persons with atopic dermatitis. It is a secondary papulovesicular eruption in response to a remote immunologic insult such as a fungal, bacterial, viral, or parasitic infection.1 The cutaneous manifestations result from delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions mediated by host T lymphocytes.2 Treatment consists of topical emollients, antibiotics, and antihistamines. In severe cases, treatment with corticosteroids may be indicated.1,2

Autoeczematization, or id reaction, is particularly common in persons with atopic dermatitis. It is a secondary papulovesicular eruption in response to a remote immunologic insult such as a fungal, bacterial, viral, or parasitic infection.1 The cutaneous manifestations result from delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions mediated by host T lymphocytes.2 Treatment consists of topical emollients, antibiotics, and antihistamines. In severe cases, treatment with corticosteroids may be indicated.1,2

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in U.S. children is 10% to 20%.3 It is the most common chronic skin disease in children, and recent data show that its prevalence is increasing.4 Consequently, the number of cases of secondary id reaction from an exacerbation of atopic dermatitis also may be increasing.

Patients with atopic dermatitis are susceptible to colonization and infection with S aureus.5 Staphylococcal species (including S aureus) have been isolated from various animals, including hedgehogs.6 In our patient, direct contact with a pet hedgehog was the likely cause of the primary staphylococcal dermatitis in her right palm that led to an exacerbation of underlying, previously undiagnosed atopic dermatitis and the subsequent development of an id reaction.

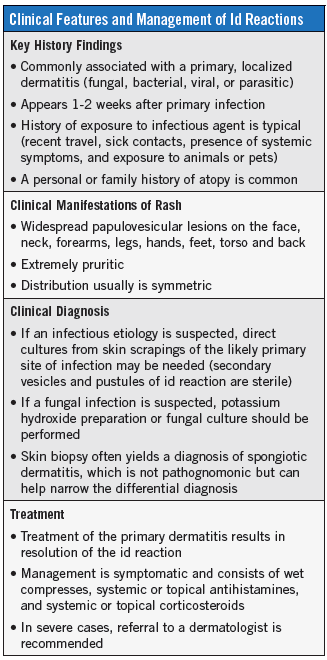

Eczematous dermatitides are very common and often present a diagnostic challenge. The accompanying Table lists the key features of id reactions and their diagnosis and management. Taking a comprehensive history of all of a patient’s potential exposures to infection is essential to making an accurate diagnosis. When an id reaction is suspected, timely identification and elimination of the primary skin disorder typically leads to prompt resolution of symptoms.

Carlos A. Pérez, MD, is a resident in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Child Neurology, at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Texas.

References

1. González-Amaro R, Baranda L, Abud-Mendoza C, Delgado SP, Moncada B. Autoeczematization is associated with abnormal immune recognition of autologous skin antigens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(1):56-60.

2. Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakaş M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38(3):191-202.

3. Van Bever HPS, Llanora G. Features of childhood atopic dermatitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29(1):15-24.

4. Lin Y-T, Wang C-T, Chiang B-L. Role of bacterial pathogens in atopic dermatitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;33(3):167-177.

5. Baviera G, Leoni MC, Capra L, et al. Microbiota in healthy skin and in atopic eczema. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:436921. doi:10.1155/2014/436921.

6. Monecke S, Gavier-Widen D, Mattsson R, et al. Detection of mecC-positive Staphylococcus aureus (CC130-MRSA-XI) in diseased European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) in Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66166. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066166.