Wegener Granulomatosis

Authors:

ROBERT J. DEUTSCH, MD, MPH

Saint Barnabas Medical Center

COLLEEN O. DAVIS, MD, MPH

University of Rochester

Citation:

Deutsch RJ, Davis CO. Wegener granulomatosis. Consultant for Pediatricians. April 2012:109-112.

A 12-year-old girl with mild hypertension, bilateral lower extremity edema, and serpiginous lesions on her lower extremities, buttocks, and elbows was referred to the emergency department (ED) by her pediatrician for evaluation of acute renal failure. Her symptoms began about a month earlier. She also reported intermittent bilateral knee pain for the past 4 to 5 months. More recently, she had migratory arthralgias of her elbows, wrists, and ankles; however, there was no significant joint erythema or swelling. She admitted to fatigue and some decrease in physical activity. About 3 weeks before presentation, she had a mild upper respiratory tract infection that resolved.

The child had no history of trauma, recent travel, or exposure to sick contacts. She denied fevers, bruising, chronic cough, nasal congestion, vomiting, diarrhea, and sore throat. She was not taking medications and had no drug allergies. She was born at 35 weeks’ gestation because of maternal Hodgkin lymphoma. There was no family history of rheumatologic disease, endocrinopathy, or renal disease. Her family was of Middle Eastern origin. She lived with both natural parents and her 6 siblings who were all in good health.

On examination, temperature was 37.4ºC (99.3ºF); heart rate, 119 beats per minute; blood pressure, 132/96 mm Hg; respiration rate, 19 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air. The patient was awake, alert, and cooperative, although visibly anxious. She had pale lips and oral mucosa, with no scleral icterus, cervical lymphadenopathy, nasal discharge, epistaxis, or ulcerations. Lungs were clear bilaterally. A grade 2/6 systolic ejection murmur was heard loudest at the left upper sternal border. There was no hepatosplenomegaly. She was Tanner stage III, with normal-appearing external genitalia.

The child had full range of motion of her extremities, although she complained of elbow and ankle discomfort. A single subcutaneous nodule was palpable at the hypothenar eminence of the right hand. She had mild pedal edema bilaterally; scattered petechiae on the lower extremities; and multiple (more than 10) raised erythematous lesions of 0.5 to 1 cm on the face, elbows, forearms, buttocks, shins, and feet. The torso was spared. Neurological findings were normal.

Laboratory testing in the ED revealed the following values: white blood cell (WBC) count, 6900/µL (4800-10,800/µL); hematocrit, 21% (35%-47%); mean corpuscular volume, 77 fL (80-100 fL); platelet count, 394,000 (150,000-400,000/µL); reticulocyte count, 1.8% (0.5%-1.5%); erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 116 mm/h (0-20 mm/h); and quantitative C-reactive protein (CRP), 121 mg/L (0.00-10.00 mg/L). Electrolyte levels were normal, with the exception of blood urea nitrogen, 55 mg/dL (9-23 mg/dL); creatinine, 2.7 mg/dL (0.5-1.0 mg/dL); and glucose, 109 mg/dL (74-106 mg/dL). Liver function test results were normal. Urinalysis revealed a specific gravity of 1.010 and pH of 5.5, with 21 protein, 31 hemoglobin, 92 red blood cells (0-2/high-power field [HPF]), and 6 WBCs (0-5/HPF). There were no casts. Results of a urine pregnancy test were negative.

Additional studies included anti–streptolysin O screen; Epstein-Barr virus, parvovirus, and mycoplasma titers; serum complement levels; rheumatoid factor; antinuclear antibody screen; antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA) screen; and anti–double stranded DNA titers. Results were negative for all except the ANCA screen, which showed a titer of 1:1280.

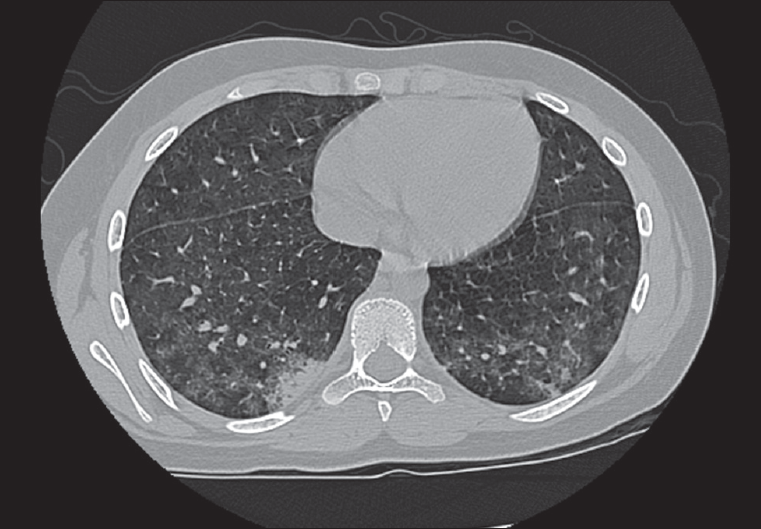

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup to include a renal ultrasonogram with biopsy. Sinus radiograph findings were normal. Chest films revealed bilateral increased interstitial markings, with no focal consolidation (Figure 1). A chest CT scan showed diffuse ground-glass opacities in the lungs, consistent with alveolitis, with small focal areas of consolidation (Figure 2). The renal biopsy specimen demonstrated segmental necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis.

Figure 1. Posteroanterior and lateral chest films show bilateral increased interstitial markings, with no focal consolidation.

Figure 2. This slide from the patient’s chest CT scan shows ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes bilaterally with a small area of consolidation in the posterior basilar segment of the right lower lobe.

In light of the positive ANCA screen and renal biopsy report, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for proteinase-3 (PR3) and myeloperoxidase was performed. Results were positive for PR3. These results, in combination with the history and physical findings, led to the diagnosis of Wegener granulomatosis (WG).

Discussion >>

WEGENER GRANULOMATOSIS: AN OVERVIEW

WG is a granulomatous, necrotizing vasculitis characterized by inflammation of the upper and lower respiratory tracts and, in most cases, the kidneys. The condition is named for the German pathologist who described 3 patients with similar unusual presentations.1 Unexplained constitutional symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, are often part of the initial disease presentation.

The prevalence of WG is about 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 30,000 persons. The disease affects males and females equally and persons of all ages (with the earliest onset reported at 2 weeks of age) and is most common in Caucasians.2-5 Attempts have been made to identify a genetic predisposition or infectious origin for the disease; however, no cause for WG has been found.2

Mild or slowly advancing disease may go unrecognized and lead to delays in diagnosis and institution of therapy. The illness course may be indolent or rapidly progressive. Although a potentially milder form of WG without renal involvement has been described, this is not the norm. Of patients who present without renal involvement, it is impossible to identify those who will have the limited, non-renal form of the disease.2

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

WG affects nearly every organ system.

Upper airway.Upper airway disease is the most common presentation and may manifest as nasal or oral ulcerations, epistaxis, mucosal swelling, external saddle-nose deformity (Figure 3), acute or chronic sinusitis, or laryngeal disease.2 Stridor with subglottic stenosis is highly characteristic of laryngeal disease.2,4,5

Figure 3. Saddlenose deformity is shown here in another patient with Wegener granulomatosis. (Courtesy of Raja Shekhar R. Sappati Biyyani, MD)

Lung.Pulmonary disease is a hallmark of WG and is present in nearly half of cases at the time of presentation. Common symptoms include cough, hemoptysis, and pleuritic chest pain. Radiographic findings include infiltrates (usually bilateral) and pulmonary nodules. Chest CT scans may reveal findings not detected on plain films. Up to a third of patients with pulmonary lesions on radiographs may not complain of lower airway symptoms, as was the case in this patient.2

Kidney.Renal involvement, when present, is often preceded by the extra-renal symptoms. It may range from microscopic hematuria to fulminant renal failure. The course is highly variable—it may take days to years before end-stage renal disease develops. Renal disease may be accompanied by anemia as a result of decreased erythropoietin production. Even if renal disease is not present at the time of diagnosis, close monitoring is essential. This is because progressive glomerulonephritis may develop at any time in patients who appear to have limited disease.1

Eye.Ocular manifestations of WG can vary. Any compartment of the eye may be involved. Proptosis is a poor prognostic sign for vision.2

Bone.Musculoskeletal complaints, including arthralgias and myalgias, are common in patients with WG and may be present for a long time (eg, up to 5 months, as in this patient). Arthritis is observed in a smaller subset of patients.1

Skin.Skin findings associated with WG include ulcers, palpable purpura, subcutaneous nodules, papules, and vesicles.6

Brain.Neurological involvementmay take the form of peripheral neuropathy, cerebrovascular accidents, seizures, and coma.1,2 Although neurological findings are more common in adults, fatal neurological involvement in children with WG has been described.7

Heart.Cardiac involvement in WG most frequently manifests as pericarditis.6 Patients may also pre-sent with pericardial effusion, chest pain, and rarely tamponade.8

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of WG include:

- Nasal or oral inflammation, characterized by the development of painful or painless oral ulcers or purulent or bloody nasal discharge.

- Abnormal chest radiograph showing the presence of nodules, fixed infiltrates, or cavities.

- Urinary sediment with microhematuria (greater than 5 red blood cells per HPF) or red cell casts in urine sediment.

- Granulomatous inflammation within the wall of an artery or in the perivascular or extravascular area on biopsy.

According to these guidelines, for diagnosis of WG, a patient must have at least 2 of the 4 criteria. The presence of any 2 or more criteria yields a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 92.0%.9

ANCA SCREENING

WG and other small to medium vasculitides, such as Churg-Strauss syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis, are referred to as the “ANCA-associated vasculitides.”10 ANCAs constitute a family of autoantibodies directed against various components of the neutrophil cytoplasm.11 There are 3 distinct ANCA staining patterns: cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA), perinuclear ANCA, and atypical patterns.10,12 When studies are positive for ANCA, additional testing for antigens PR3 and myeloperoxidase may be performed. These antigens are found in neutrophils and monocytes, against which autoantibodies (ANCA) may be formed. The combination of a c-ANCA staining pattern with PR3-ANCA, as seen in this patient, is closely associated with WG.10

TREATMENT

As with many other rheumatologic conditions, the mainstay of treatment remains immunosuppressive therapy for the induction of remission. This typically includes cyclophosphamide or methotrexate combined with prednisone. Once remission has been achieved and the prednisone has been tapered, azathioprine, methotrexate, leflunomide, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, or mycophenolate mofetil may be used for maintenance monotherapy. Unfortunately, relapse is common, and patients often require re-induction therapy.13

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors have been tried, especially in disease that has been otherwise refractory to standard treatment. However, these agents have not been proven effective and are associated with an increased risk of solid-organ tumors.14

PROGNOSIS

The degree of renal or pulmonary involvement at the time of diagnosis has the greatest effect on long-term prognosis. Relapse prevention and treatment of refractory cases still pose significant challenges to the treatment of WG.14 With early disease detection, aggressive therapy, careful monitoring, and, when needed, rapid intervention, patients with WG can lead longer and healthier lives.

PATIENT OUTCOME

This girl’s disease progressed to complete renal failure, requiring dialysis. She returned to the ED on multiple occasions for hypertensive urgency and emergency, seizures, as well as catheter infections and fistula problems related to dialysis treatments. She ultimately underwent a kidney transplant about 9 months after diagnosis. Since then, she has tolerated immunosuppressive therapy well, with no evidence of rejection or further complications.

Dr Deutsch is attending pediatric emergency physician with Emergency Medicine Associates. He is attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, NJ, where he also serves as coordinator for pediatric emergency medicine education.

Dr Davis is associate professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics and chief of the division of pediatric emergency medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, NY.

REFERENCES:

- Harris ED, Budd, RC, Genovese MC, et al, eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:chap 83.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Rottem M, Fauci AS, Hallahan CW, et al. Wegener granulomatosis in children and adolescents: clinical presentation and outcome. J Pediatr. 1993;122:26-31.

- Belostotsky VM, Shah V, Dillon MJ. Clinical features in 17 paediatric patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:754-761.

- Stegmayr BG, Gothefors L, Malmer B, et al. Wegener granulomatosis in children and young adults. A case study of ten patients. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:208-213.

- Duna GF, Galperin C, Hoffman GS. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995;21:949-986.

- Ulinski T, Martin H, Mac Gregor B, et al. Fatal neurologic involvement in pediatric Wegener’s granulomatosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:278-281.

- Meryhew NL, Bache RJ, Messner RP. Wegener’s granulomatosis with acute pericardial tamponade. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:300-302.

- Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1101-1107.

- Seo P, Stone JH. The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides. Am J Med. 2004;117:39-50.

- Hattori M, Kurayama H, Koitabashi Y; Japanese Society for Pediatric Nephrology. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated glomerulonephritis in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1493-1500.

- van der Woude FJ, Rasmussen N, Lobatto S, et al. Autoantibodies against neutrophils and monocytes: tool for diagnosis and marker of disease activity in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Lancet. 1985; 325:425-429.

- Hellmich B, Lamprecht P, Gross WL. Advances in the therapy of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:25-32.

- Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET) Research Group. Etanercept plus standard therapy for Wegener’s granulomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:351-361.