Peer Reviewed

Torticollis and Fever: A Case of Grisel Syndrome From Group A Streptococcus Infection

A previously healthy 2-year-old boy was hospitalized after 2 weeks of persistent fever (temperature to a maximum of 38.9°C [102°F]) and a 2-day history of neck stiffness. There was no history of cough, rhinorrhea, or dysphagia. The oropharynx could not be examined because of neck stiffness. The patient had bilateral anterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

A previously healthy 2-year-old boy was hospitalized after 2 weeks of persistent fever (temperature to a maximum of 38.9°C [102°F]) and a 2-day history of neck stiffness. There was no history of cough, rhinorrhea, or dysphagia. The oropharynx could not be examined because of neck stiffness. The patient had bilateral anterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

Blood cultures grew group A streptococcus, and a pharyngeal swab (using a rapid test) was positive for group A streptococcus antigen. The cerebrospinal fluid profile was normal. MRI scans of the patient’s neck showed a retropharyngeal phlegmon—a spreading, diffuse inflammatory reaction to infection that extends into deep submucous tissues and muscles and creates multiple small pockets of pus without true abscess formation.

The patient was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone and clindamycin for 7 days. These antibiotics were selected initially for their broad-spectrum coverage of infections related to the

oropharynx. After consultation with a pediatric infectious disease specialist, however, the antibiotics were discontinued because of concerns about possible infection with other bacteria that had not been detected by culture and rapid tests.

As the patient’s fever resolved, his range of neck movement increased and his appetite and activity level improved. He was discharged home, where intravenous clindamycin therapy was to be continued for 4 weeks. This length of therapy was based on the prehospital course and extent of the phlegmon.

The patient’s health continued to improve over the next week. However, 4 days before he was readmitted, he became irritable and lethargic. He began to refuse to rotate his neck and was increasingly fatigued. His mother noticed that he was holding his head to one side. According to a home health agent, the patient had apparently been receiving the antibiotic as prescribed.

On the day before readmission, the patient continued to show signs of fatigue and neck pain. His parents noted that while riding in their car, the patient held his neck with both hands—especially when the ride became bumpy. The patient had been afebrile since his discharge: there was no vomiting, diarrhea, cough, nasal congestion, or voice changes.

On readmission, the patient was afebrile and had normal vital signs. He was irritable, however, and lay in bed with his head tilted to the left. His oropharynx was not erythematous; the uvula was in the midline and there was no tonsillar hypertrophy. The patient was reluctant to move his neck in any direction, but especially side-to-side. There were no other notable physical findings.

Results of initial laboratory studies were as follows: white blood cell count, 8870/μL (normal, 6200 to 14,500/μL), with 61% neutrophils, 32% lymphocytes, and 7% monocytes; C-reactive protein level, 1.6 mg/dL (normal, 0 to 0.7 mg/dL); and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 75 mm/h

(normal, 10 to 15 mm/h). A repeated blood culture was not performed because the patient was afebrile. Serum electrolyte levels were normal.

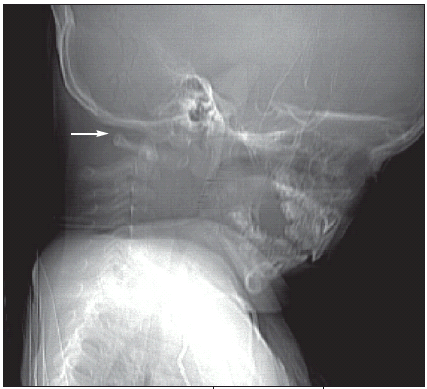

A lateral cervical spine radiograph showed subluxation (Figure 1). CT scans with contrast revealed marked anterior subluxation of C1 on C2 measuring 1 cm (Figure 2). Thickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues with an unchanged area of phlegmon was also noted. These findings were confirmed by MRI. The patient was immediately placed in a cervical collar for pain relief, and a neurosurgical consultation was obtained.

The diagnosis was Grisel syndrome— atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation secondary to the retropharyngeal phlegmon.

GRISEL SYNDROME

GRISEL SYNDROME

Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation is caused by a loss of ligamentous stability between the atlas and axis.1 First described in 1830, atlantoaxial instability can be caused by many different factors—including trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, and a variety of congenital anomalies or syndromes (including Down syndrome).1,2 In Grisel syndrome, ligament laxity is associated with pharyngeal infection or head and neck surgery.3,4 This disorder occurs primarily in children: 90% of cases occur in persons younger than 21 years.5,6

Patients typically present with painful torticollis and a history of recent or current pharyngeal infection or surgery.7-10 Anatomical studies have demonstrated the existence of a periodontal vascular plexus that drains the posterior superior pharyngeal region. Because lymph nodes are present in this plexus, septic exudates may be freely transferred from the pharynx to the C1-C2 articulation. The resulting synovial and vascular engorgements may damage the transverse and facet capsular ligaments, leading to laxity and eventual subluxation.10,11

Immobilization of the neck relieves the subluxation and prevents potential spinal cord compression. Medical management is necessary to treat the underlying infection or inflammation. The length of treatment and the apparatus used to stabilize the cervical spine is determined according to the Fielding criteria.1,6 The child in our case had a Fielding type III subluxation in which the anterior displacement measured more than 5 mm, with disruption of the transverse, alar, and tentorial ligaments and some bony erosion. The facet capsular ligaments appeared to be less involved in this case. This type of subluxation requires placement of a halo orthosis or C1 to C2 fixation.1,6

Subluxations with 3 to 5 mm of anterior displacement are classified as Fielding type II, and represent transverse ligament and unilateral facet capsular injury. Patients with this type of injury may be immobilized with a Philadelphia collar. Patients with a Fielding type I injury— with less than 3 mm of anterior displacement—have an intact transverse ligament with bilateral facet capsular injury: they can be treated with a soft collar.

Because the child in our case had an infection in the retropharyngeal area, the neurosurgeons elected to place him in a halo orthosis and planned for fixation after the infection had cleared. CT scans following halo placement demonstrated a reduction of the subluxation but also revealed an area of osteomyelitis and erosion on the odontoid process. Intravenous antibiotic therapy was therefore continued for 6 weeks before surgery was undertaken.

This patient’s case was unique in that Grisel syndrome was caused by a retropharyngeal phlegmon secondary to group A streptococcus infection. A review of the literature revealed several reports of Grisel syndrome following head and neck procedures, such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Additional cases of Grisel syndrome as a result of retropharyngeal abscess, otitis media, mastoiditis, and viral infections have also been reported. There were no reports, however, of Grisel syndrome specifically following a group A streptococcus infection.

LESSONS FOR THE CLINICIAN

Grisel syndrome is a rare complication of pharyngeal infections and inflammation. The diagnosis should be considered in any child who presents with worsening symptoms and torticollis following a pharyngeal or retropharyngeal infection or recent head or neck surgery. Also consider Grisel syndrome in patients who present with new-onset torticollis that is painful or resistant to manipulation.

Cervical spine films (including a lateral film) aid in the diagnosis. Keep in mind that the initial radiological evaluation may show normal findings. CT scans with reconstructions are necessary if Grisel syndrome is still being considered; images will show minimal subluxations that may still require immobilization. Follow-up scans may be necessary to establish the diagnosis in patients with persistent symptoms.