A Teenager With an Itchy, Round Rash Spreading Over Her Body

A 14-year-old African American girl with past medical history of asthma and a family history of eczema presented with a 3-month history of progressively worsening pruritic rash. The rash had begun as a single circular lesion on the upper area of her medial right leg. She had been treated 2 months previously with a topical antifungal agent at an urgent care facility for a presumed ringworm infection. However, the rash continued to progressively increase in size and spread to her left leg.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the girl visited the urgent care center a second time; again she was treated for ringworm, this time with tetracycline and a topical antifungal cream, and was advised to try oatmeal baths to soothe the itchiness. However, the rash continued to spread from the distal areas to the more proximal areas of her upper and lower extremities and eventually to the back of her neck.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were within normal limits. Physical examination revealed an annular, erythematous, patch-like rash with raised borders bilaterally on her upper and lower extremities, with one patch on the right side of the back her neck, below the hairline. The lesions varied in size from 2 to 5 cm, with several draining serosanguineous fluid, although the rash was not vesicular. The palms and soles were not involved.

What’s causing these pruritic, circular lesions?

A. Psoriasis

B. Tinea versicolor

C. Granuloma annulare

D. Nummular eczema

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: D, nummular eczema

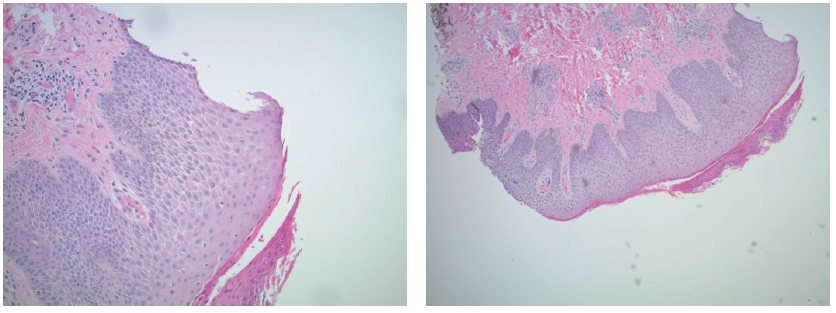

Results of punch biopsies of lesions on the right lower and left upper extremities showed spongiotic dermatitis. Histologic tissue sections showed keratosis, spongiosis, and parakeratosis with serum crust. There was a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with melanin incontinence and focal red blood cell extravasation. No significant numbers of eosinophils were seen. Periodic acid–Schiff stain results were negative for fungal organisms, and iron hematoxylin staining results were negative for hemosiderin deposition.

The patient received a diagnosis of nummular eczema. As with other forms of eczema, nummular eczema largely is a clinical diagnosis. The location of the lesions is important for diagnosis, since nummular eczema most frequently involves the dorsa of the hands and feet and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities.

Even though the lesions of nummular eczema may look like those of fungal skin infections such as tinea versicolor, pruritus is the clinical differentiating factor. Biopsy can be used to aid in the diagnosis; in nummular eczema, specimens will show spongiotic dermatitis, which is absent in fungal skin infections.1

Discussion

Nummular eczema is a common dermatologic condition with an unknown etiology. It is characterized by lesions that are coin-shaped, red plaques ranging in diameter from 1 to 5 cm. The pathophysiology of nummular eczema is not well understood, but some have speculated that xerosis is associated with the condition. Dryness of the skin results in dysfunction of the epidermal lipid barrier, allowing the permeation of environmental allergens that induce an allergic or irritant response.2,3 Patients generally present with a history of pruritus that waxes and wanes depending on the weather and that may improve with the application of emollients.

The lesions of nummular eczema evolve from solid plaques to having a peripheral papulovesicular border.4 There often is concern for superinfection with normal skin flora, at which point the lesions can develop serosanguineous exudates.

Because the pathophysiology of nummular eczema involves xerosis, treatment is geared toward hydration measures, along with the management of bacterial superinfection. Patients are advised to bathe once or twice a day with lukewarm water, followed by the application of moisturizers that help seal moisture into the skin.5

A short course of mid- to high-potency corticosteroids also can be used to reduce inflammation. Antihistamines may help reduce the itching and improve the patient’s comfort. In cases of secondary infection, oral antibiotics such as cephalexin or erythromycin should be prescribed.

Figure: Histologic tissue sections showed keratosis, spongiosis, and parakeratosis with serum crust. There was a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with melanin incontinence and focal red blood cell extravasation.

Irene Murema, MD, is a first-year resident in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Nevada School of Medicine in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Munira Rahman, DO, is a first-year resident in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Nevada School of Medicine in Las Vegas, Nevada.

References

1. Habif TP, Campbell JL Jr, Chapman MS, Dinulos JGH, Zug KA. Eczema. In: Habif TP, Campbell JL Jr, Chapman MS, Dinulos JGH, Zug KA. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:chap 2.

2. Aoyama H, Tanaka M, Hara M, Tabata N, Tagami H. Nummular eczema: an addition of senile xerosis and unique cutaneous reactivities to environmental aeroallergens. Dermatology. 1999;199(2):135-139.

3. Ozkaya E. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(4): 579-582.

4. Halberg M. Nummular eczema. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(5):e327-e328.

5. Gutman AB, Kligman AM, Sciacca J, James WD. Soak and smear: a standard technique revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(12):1556-1559.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Pisespong Patamasucon, MD, a pediatrician and pediatric infectious disease specialist and an associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Nevada School of Medicine in Las Vegas, Nevada.