ABSTRACT: Primary care providers should obtain hearing testing whenever a patient presents with a sudden change in hearing. Although often confused with the transient hearing loss that commonly results from upper respiratory tract infections, sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) may be a consequence of either a primary neoplasm originating within the temporal bone or a secondary neoplasm metastasizing to the temporal bone. Acoustic neuroma and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the breast are the most commonly identified primary and secondary neoplasms, respectively. Once considered rare, secondary metastatic lesions are being reported in far greater numbers than had previously been appreciated. Two illustrative cases of SSNHL are described herein, the first resulting from an acoustic neuroma and the second associated with adenocarcinoma of the breast metastasizing to the temporal bone.

KEYWORDS: Sudden sensorineural hearing loss, acoustic neuroma, secondary neoplasm of the temporal bone, hearing testing, magnetic resonance imaging

Approximately 1 in 8 individuals aged 12 years or older in the United States have a bilateral hearing loss, and 1 in 5 have a unilateral hearing loss.1 Disorders anywhere along the auditory pathway from the external auditory canal to the central nervous system may result in diminished hearing. Patients presenting with sudden hearing loss, however, demand a more urgent and vigilant approach, given that rapid diagnosis and treatment may increase the possibility of hearing recovery as well as lead to the earlier identification of potentially treatable pathology.

The National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders has defined sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) as a decrease in hearing of 30 dB or greater across at least 3 consecutive frequencies over a period of 3 days or less.2 Others have sought to expand the definition by including individuals who simply experience a sensorineural loss in fewer than 3 days.3,4 SSNHL has long bedeviled clinicians and sufferers alike in that the etiology in up to 90% of cases remains elusive.3 The remaining 10% or so of cases have been associated with neoplastic, autoimmune, infectious, circulatory, coagulation, and demyelinating disorders.5,6

Although hearing loss is the preponderant otologic manifestation noted to occur in primary and secondary neoplasms of the temporal bone, tinnitus, disequilibrium, and vertigo also may present in either group. Acoustic neuroma (AN) is a benign lesion that commonly arises from the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII) and may be located in the internal auditory canal, cerebellopontine angle, or both sites simultaneously. The secondary group, comprising malignant neoplasms that have metastasized to the temporal bone, may involve regional and/or distant sites, resulting in a number of unanticipated clinical signs and symptoms. Health care providers should be highly suspicious of an underlying malignancy when a patient presents with either a sudden bilateral hearing loss or a unilateral loss in the presence of pain, dizziness, facial nerve paralysis, or chronic ear discharge.7 Secondary malignant lesions often represent primary neoplasms with a propensity to invade bone.8 Carcinoma of the breast is the most prevalent neoplasm to metastasize to the temporal bone.9,10

Case Report 1

A 63-year-old man presented with a sudden change in hearing in the right ear that he had first appreciated approximately 3 to 4 days prior to his visit. He also reported a clogged sensation and tinnitus in the affected ear along with slight episodic disequilibrium. There was no recent history of upper respiratory tract infection, acoustic trauma, or manipulation of the ear canal. His medical history was notable for hypercholesterolemia and hypertension; his medications included losartan, atorvastatin, and a daily aspirin.

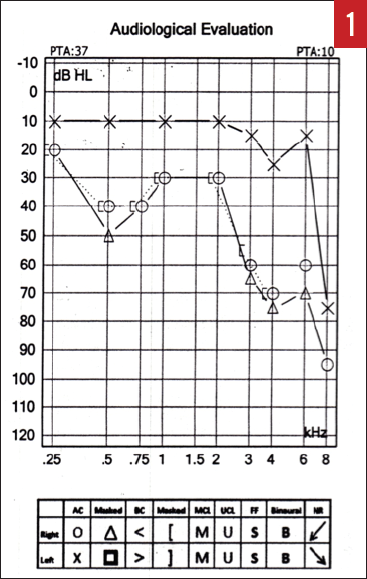

Physical examination of the ears, nose, and throat failed to identify any pathology. An immediate hearing test was obtained, the results of which revealed a significant asymmetry between the right and left ears, with a moderate to moderately severe hearing loss involving the right ear (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Audiogram of the patient with a right AN who presented with SSNHL (case report 1).

The patient was started on a prednisone 60-mg taper over a 2-week period, which resulted in slight improvement in his hearing. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the internal auditory canals with gadolinium contrast identified an approximately 0.7 × 0.5 × 0.3-cm enhancing mass within the right internal auditory canal suggestive of an AN (Figure 2). After appropriate consultation, the patient elected to undergo stereotactic radiosurgery, and he is being carefully monitored.

Figure 2. MR imaging revealing an enhancing mass in the right internal auditory canal (arrow) consistent with acoustic neuroma (case report 1).

Case Report 2

A 74-year-old woman was seen in consultation for a sudden change of hearing in the right ear upon awakening 2 days prior to her initial visit. She denied any concurrent vertigo, tinnitus, aural fullness, or prior history of ear disease. Her medical history was notable for temporal arteritis, hypertension, and carcinoma of the left breast that had resulted in a mastectomy 15 years prior to her consultation. Her medications included aspirin, simvastatin, tamoxifen, fosinopril, prednisone, and diltiazem. At the time of the visit, she was also being attended to by an oncologist because of metastatic carcinoma of the breast to the skull and other locations.

Examination of the ears, nose, and throat failed to identify any pathology. No cranial nerve deficits were detected. Audiometric testing was performed (Figure 3), and a presumptive diagnosis of SSNHL was made based on her history and the significant difference in hearing acuity between the right and left ears.

Figure 3. Audiogram of the patient with metastatic carcinoma of the breast to the skull/temporal bone who presented with SSNHL in the right ear (case report 2). The results reveal asymmetric hearing loss.

MR imaging of the brain (Figures 4 and 5) identified diffuse epidural enhancement, as well as enhancement in the right internal auditory canal. Inasmuch as this patient was on low-dose prednisone for temporal arteritis, intratympanic steroid treatment was utilized but brought about no improvement in hearing acuity.

Figure 4. Axial MR image identifies diffuse epidural enhancement along with convexities that represent direct epidural extension from calvarial metastatic disease (case report 2).

Figure 5. Coronal MR imaging showing slight enhancement within the right internal auditory canal, likely secondary to epidural disease (case report 2).

Assessment of Hearing Loss

SSNHL is a symptom that should compel patients to seek urgent care and prod health care providers to arrange for immediate assessment so that appropriate treatment is instituted in a timely fashion. Aural fullness and muffled hearing commonly occur in the presence of nasal allergies and upper respiratory tract infections and typically resolve spontaneously or with conservative medical management. A good number of patients with sudden hearing loss are first attended to in primary care settings where hearing assessment is generally not obtained. Many of these patients are inappropriately reassured, with the loss in hearing often attributed to middle ear problems likely resulting from an upper respiratory tract infection.5 A methodical clinical history and a comprehensive physical examination should be performed, along with prompt hearing testing.

Approximately 90% of SSNHL cases have been designated as idiopathic, with a wide spectrum of disorders constituting the remaining 10%. Potential disorders found to be associated with SSNHL include ear-specific and systemic immune-mediated disorders, coagulopathies, posterior circulatory events, demyelinating diseases, infectious diseases, disorders resulting in endolymphatic hydrops (Meniere disease), and both primary and secondary neoplasms.5 Although 32% to 65% of cases have been reported to resolve spontaneously, any delay in diagnosis and treatment may negatively impact recovery.6

Conditions that result in a nonsensorineural hearing loss should be considered in the differential diagnosis of SSNHL. A conductive hearing loss often results from problems relating to the external ear canal, tympanic membrane, or middle ear space. The presence of an obstructed external auditory canal (impacted cerumen or a foreign body), perforation of the tympanic membrane (traumatic or resulting from infection), and middle ear pathology (otitis media, eustachian tube dysfunction) have all been identified as potential causes of a sudden change in hearing. Pseudohypacusis is a nonorganic loss in which there is no clinical or audiologic evidence of hearing loss. Often psychogenic in origin, this hearing loss is frequently encountered in children and young women.6 Physical examination and hearing testing generally suffice in identifying these conditions and serve as a means by which to differentiate SSNHL from a sudden conductive loss of hearing.

Treatment of SSNHL

Treatment depends upon the cause of SSNHL. Inasmuch as most cases are idiopathic in nature, high-dose oral corticosteroids have been and continue to be utilized. Intratympanic steroid therapy has become a well-established therapeutic option and is used as the initial treatment of choice as salvage therapy should oral corticosteroids fail and in patients in whom oral corticosteroids are contraindicated. Although the use of vasodilators, antivirals, and thrombolytics has been proposed, a clinical practice guideline on sudden hearing loss recommends against their routine usage.6 Both spontaneous recovery and improvement with use of corticosteroids have been found to occur primarily during the first 2 weeks following the initial onset of hearing loss. A permanent sensorineural loss that is no longer responsive to treatment may occur in cases in which therapy was ignored or delayed.

SSNHL and AN

A diagnosis of SSNHL warrants prompt evaluation because of possible involvement of either a primary or secondary neoplasm within the temporal bone. AN, also referred to as vestibular schwannoma, is a benign neoplasm that typically arises within the internal auditory canal and originates from the Schwann cells that populate the myelin sheath of the vestibular branch of the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII). AN represents an estimated 6% of all cranial tumors and has been found to be the most common primary neoplasm associated with SSNHL.11 Studies indicate that approximately 19% of ANs give rise to SSNHL, including small neuromas confined entirely to the internal auditory canal.12 Other primary neoplasms that originate in the temporal bone include chemodectoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma, all of which occur in far fewer numbers.5,13

A majority of ANs likely remain clinically silent because of exceedingly slow or arrested growth. Rosenberg14 posits that less than 1% of all AN cases demonstrate sufficient growth needed to become clinically apparent. SSNHL is becoming a more common finding in cases of AN, as heretofore undetected cases of AN are being discovered on a more regular basis.12 As reliability and efficiency of imaging studies increases, the discovery of clinically silent lesions is occurring with greater frequency. Patients who have a long history of asymmetric hearing loss and negative findings on past imaging studies should perhaps be reassessed with updated, more sophisticated MR imaging.14

Although hearing loss is the most common symptom occurring in AN, an array of other complaints has been well documented. Small to medium lesions may give rise to unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, unsteadiness, dizziness, otalgia, headache, or facial weakness. Facial weakness, dysphagia, dysarthria, and hydrocephalus can occur when larger lesions are present. An enlarging lesion in contact with the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) may result in either numbness or sensory changes involving the tongue and/or face. Continued growth may lead to headache and assorted difficulties with vision, gait, and swallowing.15,16 Treatment of AN includes surgical excision, radiation therapy, or conservative management via careful clinical monitoring and imaging follow-up. Treatment options depend upon a number of variables relating to tumor size, degree of hearing loss, medical comorbidities, patient age, and patient preferences.15,17

SSNHL and Metastatic Cancer

Early reports detailing metastatic involvement of the temporal bone initially had been viewed as isolated and rare. Proctor and Lindsay18 were able to identify only a single case of metastasis in their histopathologic assessment of selected temporal bones in 1947. The overall number of reported cases has seemingly been on the rise; this increase has been attributed in part to an increase in the incidence of malignant diseases, as well as longer survival rates.19 Nelson and Hinojosa20 maintain that the temporal bone, once commonly ignored during routine postmortem examinations, is beginning to receive the attention it rightly deserves. Perhaps most importantly, imaging studies have proven invaluable in identifying metastatic neoplasms of the temporal bone that may have heretofore remained silent and undetected.7,21

The true incidence of metastatic involvement of the temporal bone is likely underestimated because of the prominence of other sites of involvement and the occasional lack of significant symptomatology.19 Notable differences in occurrence rates add a degree of uncertainty to the question of prevalence. In their assessment of 1200 temporal bones, Nelson and Hinojosa20 came across a relatively small number of metastatic neoplasms, identifying only 60 such cases. Temporal bones from 212 patients with cancer were evaluated by Gloria-Cruz and colleagues,9 who calculated an approximate prevalence of 22.2%. Carcinoma of the breast is unquestionably the most prevalent primary neoplasm, with the lung, prostate, kidney, skin, cervix, brain, liver, and stomach representing other less-common sites of origin.9,20 Irrespective of primary neoplasm, adenocarcinoma constitutes the most common histopathologic classification found to metastasize to the temporal bone.8

Metastatic involvement of the temporal bone typically straddles the extremes of clinical presentation. At times, signs and symptoms may be immediate and obvious. There are, however, occasions when a delay in diagnosis occurs either because of a lack of symptoms or because symptoms prove to be remarkably similar to cases of inflammatory disease of the external and middle ear.18,22 Arriving at a definitive and timely diagnosis may prove daunting. Although hearing loss has been identified as the most frequent otologic symptom of metastatic involvement, there are instances in which patients, including those with advanced disease, remain entirely asymptomatic. Manifestations of metastatic involvement may surface only when metastatic foci extend into locations that are likely to give rise to otologic signs and symptoms.7

As in our case, whenever hearing loss or related complaints present in an individual with a diagnosed malignancy, suspicion of metastatic spread to the temporal bone must be entertained.

The Take-Home Message

A complaint of sudden change in hearing should not be taken lightly. It is imperative that primary care providers obtain an appropriate history, comprehensive physical examination, and immediate hearing testing. A diagnosis of SSNHL calls for an urgent otolaryngology consultation.

Health care providers should recognize that both primary and secondary neoplasms of the temporal bone may first present with hearing loss, commonly in the guise of SSNHL or as an asymmetric loss of hearing. Audiometry and MR imaging with contrast are pivotal in arriving at a proper diagnosis and often serve as essential pieces in a potentially complicated treatment puzzle. Such is indeed the case with secondary neoplasms with metastatic foci that can involve a wide range of disparate sites, resulting in unexpected symptoms and perplexing clinical presentations.

Sheldon P. Hersh, MD, is an otolaryngologist in private practice in Queens, New York, and is affiliated with the Department of Otolaryngology at Lenox Hill Hospital/Northwell Health in New York, New York.

Joshua N. Hersh, MD, is a neurologist at Princeton and Rutgers Neurology in Somerset, New Jersey.

REFERENCES:

- Lin FR, Niparko JK, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1851-1852.

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. NIDCD Fact Sheet: Hearing and Balance: Sudden Deafness. NIH publication 13-4757. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/health/hearing/NIDCD-Sudden-Deafness.pdf. Updated November 2013. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- O’Malley MR, Haynes DS. Sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(3):633-649.

- Spear SA, Schwartz SR. Intratympanic steroids for sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(4):534-543.

- Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haskard DO, Luxon LM. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet. 2010;375(9721):1203-1211.

- Stachler RJ, Chandrasekhar SS, Archer SM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3 suppl):S1-S35.

- Cureoglu S, Tulunay O, Ferlito A, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, Rinaldo A. Otologic manifestations of metastatic tumors to the temporal bone. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124(10):1117-1123.

- Stucker FJ, Holmes WF. Metastatic disease of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope. 1976;86(8):1136-1140.

- Gloria-Cruz TI, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, Adams GL, Fulton SE. Metastases to temporal bones from primary nonsystemic malignant neoplasms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(2):209-214.

- Falcioni M, Piccirillo E, Di Trapani G, Romano G, Russo A. Internal auditory canal metastasis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004;24(2):78-82.

- Lin D, Hegarty JL, Fischbein NJ, Jackler RK. The prevalence of “incidental” acoustic neuroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(3):241-244.

- Yanagihara N, Asai M. Sudden hearing loss induced by acoustic neuroma: significance of small tumors. Laryngoscope. 1993;103(3):308-311.

- Nadol JB Jr. Hearing loss. N Engl J Med. 1993:329(15):1092-1102.

- Rosenberg SI. Natural history of acoustic neuromas. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):497-508.

- Karpinos M, Teh BS, Zeck O, et al. Treatment of acoustic neuroma: stereotactic radiosurgery vs. microsurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(5):1410-1421.

- Wiegand DA, Fickel V. Acoustic neuroma—the patient’s perspective: subjective assessment of symptoms, diagnosis, therapy, and outcome in 541 patients. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(2):179-187.

- Smouha EE, Yoo M, Mohr K, Davis RP. Conservative management of acoustic neuroma: a meta-analysis and proposed treatment algorithm. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(3):450-454.

- Proctor B, Lindsay JR. Tumors involving the petrous pyramid of the temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1947;46(2):180-194.

- Berlinger NT, Koutroupas S, Adams G, Maisel R. Patterns of involvement of the temporal bone in metastatic and systemic malignancy. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(4):619-627.

- Nelson EG, Hinojosa R. Histopathology of metastatic temporal bone tumors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117(2):189-193.

- Moffat DA, Saunders JE, McElveen JT Jr, McFerran DJ, Hardy DG. Unusual cerebello-pontine angle tumours. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107(12):1087-1098.

- Adams GL, Paparella MM, El Fiky FM. Primary and metastatic tumors of the temporal bone. Laryngoscope. 1971;81(8):1273-1285.