Screening, Staging, and Assessment of Colorectal Cancer: A Cautionary Case

ABSTRACT: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the United States. Because of this high incidence rate, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends CRC screening in adults with no risk factors via fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy beginning at age 50 until age 75 and on an individual basis thereafter. Adults with CRC risk factors may begin screening before age 50 and be screened more frequently than those without CRC risk factors. Using a case report of a 78-year-old man in whom a colonoscopy with biopsy and a computed tomography scan appeared to reveal a tubulovillous adenoma in the cecum but who later was found to have invasive adenocarcinoma in the rectal vault that had been missed on initial colonoscopy, this article reviews the screening for, staging of, and diagnostic assessment of CRC.

KEYWORDS: Tubulovillous adenoma, invasive adenocarcinoma, screening colonoscopy, hemicolectomy, diverting colostomy placement, fecal occult blood test

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer among US men and women, with an estimated 134,490 new cases having occurred in 2015.1 Due to the high incidence rate of CRC, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for the disease in adults with no risk factors via fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy beginning at age 50 until age 75 and on an individual basis in adults older than age 75.2 For adults with risk factors such as a family history of CRC, beginning screening for the disease before age 50, and screening more frequently than for those without risk factors, may be considered.2

This case report documents the case of a 78-year-old man who presented to a general surgeon’s office for a consultation about his symptomatic hemorrhoids and the presence of bright red blood in his stool. A colonoscopy with biopsy revealed a tubulovillous adenoma in the patient’s cecum; a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis also showed a cecal mass. The patient underwent a right hemicolectomy, during which the tumor was found to be in the hepatic flexure and not in the cecum. This discrepancy was thought to be related to poor bowel preparation for the initial colonoscopy, so a repeat colonoscopy was performed during the hemicolectomy, which showed a second invasive adenocarcinoma in the rectal vault that had been missed on the initial colonoscopy. A right hemicolectomy with excision of the rectosigmoid junction with diverting colostomy was then performed to remove all of the cancerous tissue in the colon and rectum.

SCREENING FOR CRC

The USPSTF recommends screening for CRC beginning at age 50 until age 75 years using various methods. Among the numerous screening methods, the 3 most commonly recommended are FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy.2 FOBT should be repeated annually; however, there are problems with relying solely on the results of FOBT as a CRC screening method. Not all CRCs bleed, and even fewer adenomas bleed, which means they will not be detected on FOBT. This might explain the low sensitivity (ranging from 1% to 27% for adenomas and 50% for CRC) of FOBT.2 However, the specificity for FOBT is approximately 98%, which makes it a better confirmatory test than a screening test due to the positive predictive value ranging from 5% to 10%.2

Every positive FOBT result requires follow-up with a more expensive and more invasive test, which may lead to unnecessary procedures based on false-positive results. Nevertheless, despite the problems with the test’s sensitivity and specificity, annual FOBT has been shown to be approximately equal to other screening methods in life-years gained, assuming 100% patient adherence.

Another method of CRC screening is with flexible sigmoidoscopy, during which interior walls of the rectum and the descending colon are assessed.3 Flexible sigmoidoscopy also allows the physician to obtain tissue biopsy samples for pathology evaluation, to remove polyps, and to tattoo any lesions that are found for easy localization during surgical resection.3

Flexible sigmoidoscopy has a high sensitivity and specificity, which makes it a better screening test than FOBT. However, because the procedure only allows visualization of the rectum and the first portion of the colon, repeating flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years and performing a FOBT every 3 years is recommended. This approach has been shown to increase the detection of CRC and adenomas over using flexible sigmoidoscopy alone.2

A colonoscopy is much like a flexible sigmoidoscopy, except that it can visualize the transverse and ascending portions of the colon along with the descending colon and the rectum.4

Once a lesion has been identified using screening techniques, a biopsy is performed, and a tissue sample is evaluated histologically to determine whether the lesion is cancerous or benign. Further diagnostic imaging and laboratory tests are then used to determine the lesion’s size, the presence of local tissue invasion, and whether the lesion has metastasized. If the lesion is determined to be malignant, the next step is staging.

STAGING AND TREATMENT OF CRC

The staging process is used to determine the extent to which cancer has spread in the body, with the cancer assigned a number from 0 to IV based on criteria corresponding to tumor invasion (T), lymph node involvement (N), and metastasis (M) (Table).5

Treatment of colorectal cancer is largely dependent on the cancer stage at the time of detection.2 For cancer at stage 0, a simple polypectomy or local colonoscopic excision may be performed, since the tumor typically has not grown past the inner lining of the colon. Occasionally, the affected portion of the colon may require resection if it is too large to be removed with local excision.6

Once the cancer becomes stage I or higher, treatment begins to vary based the results of histologic evaluation. For a stage I tumor whose cancerous cells are deemed to be entirely confined within the polyp, a simple polypectomy is appropriate. However, if cancer cells are present at the margins of the polyp, or if the polyp has been removed in pieces, further surgical resection of the affected area of the colon is indicated. If the tumor is not part of a polyp, the affected area of the colon must be removed, and an anastomosis of the adjacent cancer-free sections of bowel must be performed.6

Stage II tumors are typically treated with a partial colectomy and anastomosis. If the entire tumor is removed during the colectomy and the patient has few risk factors, no further treatment is indicated. However, if a patient has a history of recurrence, a family history of CRC, or numerous risk factors, adjuvant chemotherapy may also be indicated to prevent recurrence.6

For stage III tumors, a partial colectomy with anastomosis and lymph node resection is indicated, along with adjuvant chemotherapy such as fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin. After the specimen has been removed, it is evaluated by a pathologist to determine whether the cells in the margins around the cut portions of tissue are normal or premalignant. The presence of normal tissue cells indicates that the entirety of the lesion has been removed. However, if premalignant cells are present in the margins, it is likely that not all of the premalignant cells have been removed. If the possibility exists that cells of a premalignant lesion were left behind during the procedure, radiation treatment may be indicated, as well.6

Stage IV tumors have metastasized to nearby organs and lymph nodes, and surgical resection of the affected portion of the colon and, if possible, any organs containing the metastasis is indicated, along with the addition of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. For cases of cancer this advanced, surgery is not always curative, but it is thought to prolong survival by removing symptoms of the disease.6

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old man was referred to a general surgeon’s office with concern for rectal bleeding and symptomatic external hemorrhoids of 2 months’ duration. This had been the first time the patient had experienced symptoms of rectal bleeding and hemorrhoids.

History. The man was a former cigarette smoker with a history of prior chewing tobacco use. He denied alcohol use. His past medical history was significant for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and kidney stones. His past surgical history included a lumbar laminectomy, heart catheterization, quadruple coronary artery bypass grafting, appendectomy, and kidney stone removal.

During the visit with the general surgeon, the patient reported that approximately twice a month, he would pass bright red blood with bowel movements. He had noticed the blood in the toilet and also on the toilet paper. He was also reported experiencing burning and bleeding from his external hemorrhoids, passing large-caliber stools, and having to strain more than he had used to in order to evacuate his colon.

Physical examination. The patient had mild to moderate rectal stenosis and grade 4 external hemorrhoids at the 7-o’clock position. The remaining physical examination findings were unremarkable.

After receiving preoperative cardiac clearance, the patient was scheduled for a colonoscopy and hemorrhoidectomy.

Diagnostic assessment. During the colonoscopy, the patient was noted to have a large fungating mass of approximately 5 cm in diameter that appeared to extend through the mucosa in what appeared to be the cecum. The mass was biopsied 8 times to minimize biopsy sampling error, and then the margins surrounding the mass were tattooed with india ink. Large prolapsing hemorrhoids were noted within the rectal vault. As the scope was withdrawn from the rectum, the hemorrhoids began prolapsing and obstructing the anal canal. These prolapsing hemorrhoids were then removed using sharp dissection. The procedure was hindered by poor bowel preparation, which made it difficult to completely visualize the colonic mucosa.

Pathology analysis of the biopsy specimens revealed the cecal mass to be a low-grade tubulovillous adenoma with no evidence of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma.

The results of a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis done the same day showed a mass measuring 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.4 cm in the cecum, adjacent to the ileocecal valve (Figure 1).

Because the tumor was too large to remove with a colonoscope and simple excision, the patient was scheduled for a right hemicolectomy 2 months after the colonoscopy. The surgeon perceived the tumor to be in the cecum, and the CT scan report corroborated this perception.

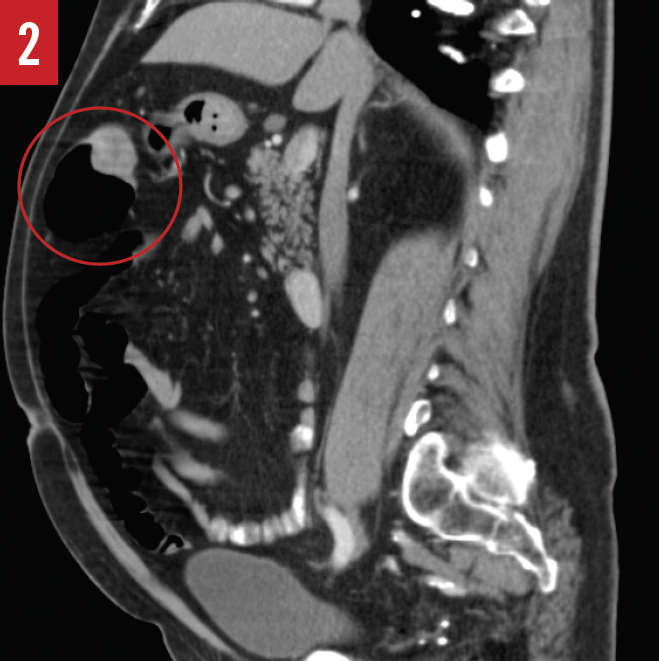

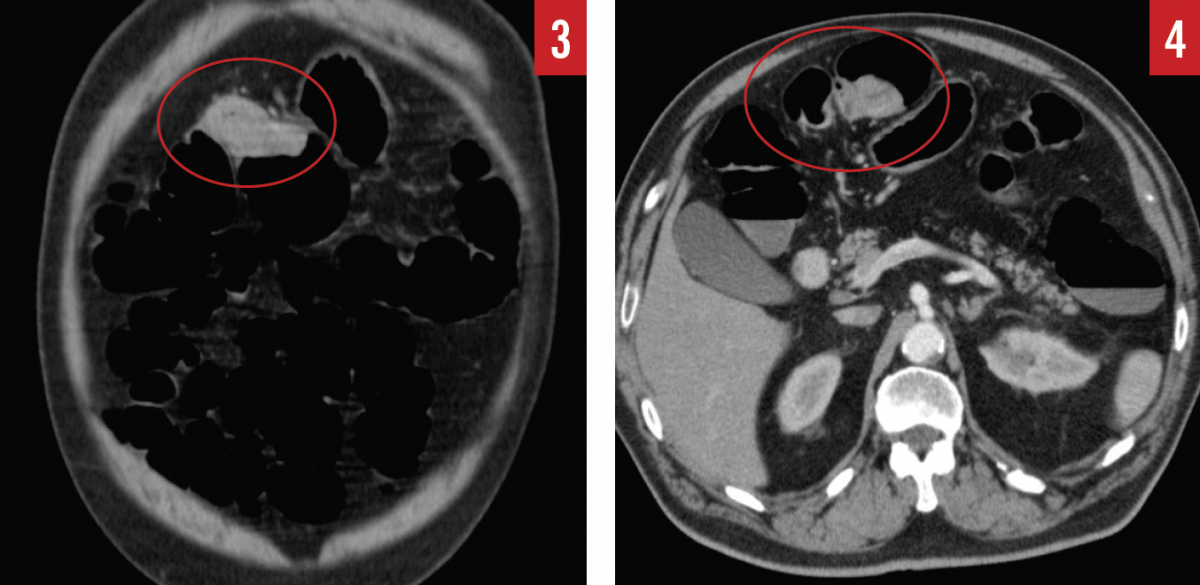

During the hemicolectomy, when the ascending colon was mobilized and palpated, the tattooing done during the colonoscopy had faded and was no longer visible due to the prolonged time between the colonoscopy and the hemicolectomy. The ascending colon was then palpated, and a firm, rubbery mass was felt within the cecum as described by CT. The ascending colon from the terminal ileum to the border of the liver was then excised and examined; however, no tumor was present within the cecum or the ascending colon, only a fatty infiltrate near the ileocecal valve. The surgeon then reviewed the CT scan and report to identify the cecal mass, at which time a mass was also noted in the hepatic flexure (Figures 2-4).

Confused by the conflicting information, the surgeon then palpated the remaining colon and felt a mass within the hepatic flexure. The hepatic flexure was then excised, and the mass was examined histologically and found to be a tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia. It became apparent that the original mass that had been visualized on colonoscopy and that had been thought to be located in the cecum was in fact in the hepatic flexure, and during the extended time between colonoscopy and hemicolectomy, the mass had progressed from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia.

The proximal end of the remaining colon was then placed adjacent to the terminal ileum and sutured into place. Anastomosis of the adjacent ends of the colon and the terminal ileum was successful.

Because the original tattooing of the colon had faded, and given the fact that the bowel preparation for the initial colonoscopy had not been optimal, the surgeon decided to perform a repeat colonoscopy to be certain that the tumor that had been removed in the hepatic flexure was indeed the tumor that initially had been visualized on colonoscopy.

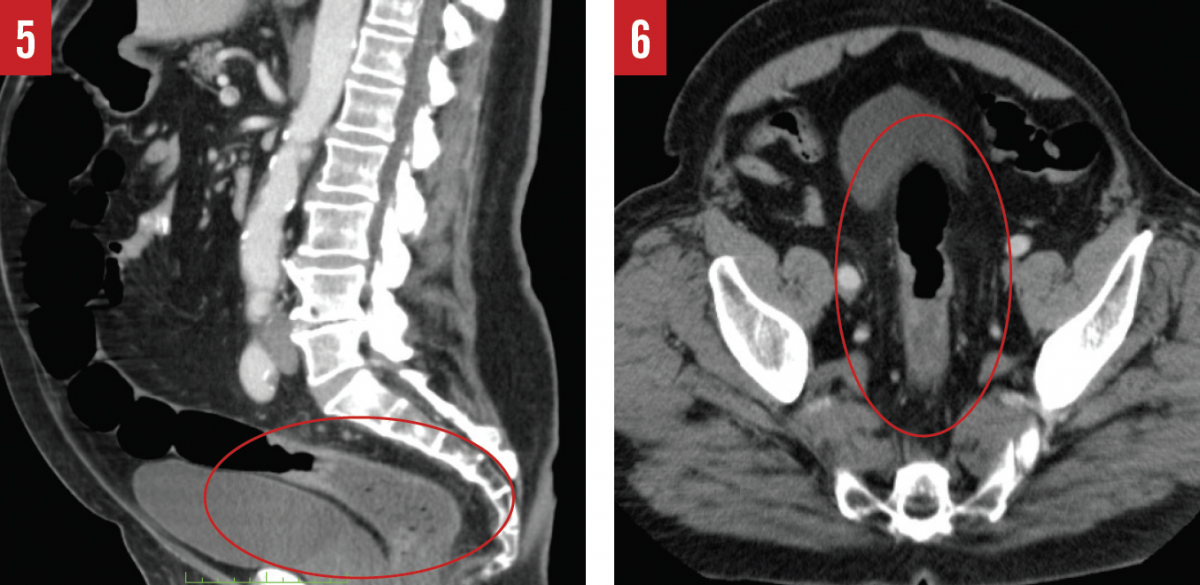

The scope was advanced to the anastomosis, and it was noted that no mass remained in the colon. Upon withdrawal of the colonoscope, however, a second mass measuring approximately 4.5 × 3.0 cm that had not originally been noticed on CT was discovered in the rectosigmoid junction (Figures 5 and 6). Biopsies were obtained and examined histologically, revealing that this mass was a stage IIIA low-grade adenocarcinoma with invasion into the muscularis propria and regional lymph nodes.

Attempts to remove the tumor with a thoracoabdominal stapler and gastrointestinal anastomosis stapler were unsuccessful due to a narrow pelvic inlet and the low-lying nature of the tumor. Instead, a scalpel was used to circumferentially excise the tumor, and the proximal end of the remaining rectum was sutured closed. The distal end of the sigmoid colon was then delivered through the abdominal wall for a diverting colostomy.

Case outcome. The patient tolerated the procedure well and had no problems in the postoperative period. He did well with the colostomy bag and was discharged from the hospital 3 days after having undergone the procedure.

DISCUSSION

Colonoscopy has a sensitivity ranging from 75% to 93% to detect adenomas larger than 6 mm.7 This depends largely on proper bowel preparation and the skill of the physician surgeon, but even under ideal conditions the sensitivity does not reach 100%.7 A sensitivity of 75% to 93% means that for every 100 cases, from 7 to 25 represent false negatives.8

Unfortunately in health care, mistakes occur that can lead to harm to a patient. In this case, however, a series of mistakes led to a better outcome for the patient.

The patient had poor bowel preparation for the initial colonoscopy. For most patients, bowel preparation is the most difficult part of a colonoscopy, and they may not understand the importance of a proper bowel preparation so that the physician can adequately visualize the internal walls of the colon.9 A poorly prepared bowel might make it difficult to visualize a tumor. While performing a colonoscopy under ideal conditions, it may be obvious what part of the colon the scope is advancing through, but if a tumor obstructs a colon that has been insufficiently prepared, it may be more difficult to ascertain which section of the colon the scope is in.

In the example case presented here, the surgeon visualized a mass in the hepatic flexure that he perceived to be in the cecum. The CT imaging and radiology report corroborated this finding, stating that there was a cecal mass but with no mention of a mass in the hepatic flexure or in the rectosigmoid junction. Nevertheless, on second look, the hepatic flexure mass was apparent on images in all 3 viewing planes, and the rectosigmoid junction showed wall thickening that should have been flagged as abnormal for further workup, as well.

The extended period between the initial colonoscopy and the procedure to remove the mass allowed it to progress from low-grade to high-grade dysplasia. During this time, the india ink tattoo also had faded, making it impossible for the surgeon to visualize the portion of colon initially identified as containing the tumor.

THE TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

After the procedure, the surgeon stated that he made the decision to re-drape the patient and perform a colonoscopy in mid-procedure based on a “gut feeling.” Had the decision not been made to repeat the colonoscopy, the patient in this case may have left the hospital after the procedure with a malignant tumor in his rectosigmoid junction.

Although colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and FOBT all have evidence supporting their efficacy in screening for CRC, more research is necessary to develop effective screening techniques that are more sensitive and perhaps less invasive than the options available today.

Luis L. Perez, DO, is a family physician at Firelands Physician Group in Huron, Ohio.

Karen Sheehan, MD, is a radiologist at Firelands Regional Medical Center in Sandusky, Ohio.

Shawn Warner, MS-III, is a student at Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio.

REFERENCES:

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7-30.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2564-2575.

- Understanding flexible sigmoidoscopy. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. https://www.asge.org/home/for-patients/patient-information/understanding-flexible-sigmoidoscopy. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- Understanding colonoscopy. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. https://www.asge.org/home/for-patients/patient-information/understanding-colonoscopy. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- Colon and rectum. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A III, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Chicago, IL: American Joint Committee on Cancer; 2010:chap 14.

- Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colon-treatment-pdq. Updated January 20, 2017. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576-2594.

- Lalkhen AG, McCluskey A. Clinical tests: sensitivity and specificity. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2008;8(6):221-223.

- Understanding bowel preparation. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. https://www.asge.org/home/for-patients/patient-information/understanding-bowel-preparation. Accessed February 28, 2017.