Peer Reviewed

Sarcoidosis Presenting as Symptomatic Hypercalcemia in an Octogenarian

Authors:

Sharon Jamie, MD, MHSA, Carl V. Tyler Jr, MD, MS, and Joseph G. Parambil, MD

Citation:

Jamie S, Tyler Jr CV, Parambil JG. Sarcoidosis presenting as symptomatic hypercalcemia in an octogenarian. Clin Geriatr. 2011;51(4).

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that generally presents in young adults and is rarely diagnosed in the elderly population. In this article, we describe a newly diagnosed case of sarcoidosis in an 88-year-old woman presenting with fatigue, profound weakness, anorexia, severe hypercalcemia, and generalized lymphadenopathy. Axillary and mesenteric lymph node biopsies demonstrated nonnecrotizing granulomas consistent with the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Because manifestations of sarcoidosis in the elderly tend to be atypical, we reviewed the published literature on the clinical presentation, barriers to definitive diagnosis, and complexities associated with treatment of this multisystem disease.

Case Presentation

An 88-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 10-day history of progressively worsening generalized weakness, fatigue, nausea, and anorexia. Five days previously, she had visited her family physician with the chief symptom of constipation, which was attributed to chronic opiate therapy prescribed for chronic low-back pain due to lumbar spondylosis. Her constipation was treated with polyethylene glycol once daily as needed. At the time of that outpatient examination, the patient’s mental status was intact, but weakness and emerging confusion prompted her family to take her to the emergency department for further evaluation.

The patient’s medical history was significant for essential hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, previously mentioned chronic low-back pain due to lumbar spondylosis with lumbar canal stenosis, and celiac disease. She had never smoked cigarettes. Five years earlier, while undergoing an evaluation for unexplained weight loss, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed mesenteric lymphadenopathy. CT-guided biopsy revealed nonnecrotizing granulomas, which the consultant hematologist attributed to celiac disease. At the time of the patient’s current admission, her medications included amlodipine 5 mg once daily, oxycodone 10 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg twice daily, furosemide 20 mg once daily, digoxin 125 mcg once daily, warfarin adjusted based on international normalized ratio levels, trazodone 50 mg nightly, and vitamin D3 2000 IU once daily.

The physical examination revealed a confused and disoriented elderly woman with dry mucous membranes, reduced skin turgor, and a blood pressure of 180/85 mm Hg. An examination of the patient’s heart, lungs, and abdomen was unremarkable. There was palpable left posterior cervical, bilateral axillary, and left inguinal lymphadenopathy. She demonstrated grade 3/5 weakness in all upper and lower extremity muscle groups, with associated mild hypotonia and normal tendon reflexes.

Pertinent abnormal laboratory findings on initial assessment included severe hypercalcemia, with a serum calcium of 15.8 mg/dL (normal: 8.2-10.2 mg/dL) and ionized calcium of 7.68 mg/dL (normal: 4.60-5.08 mg/dL); and prerenal azotemia, with a blood urea nitrogen of 58 mg/dL (normal: 8-23 mg/dL), creatinine of 1.8 mg/dL (normal: 0.6-1.2 mg/dL), and urine sodium of 11 mEq/L (normal: >20 mEq/L). Subsequent laboratory testing revealed a reduced serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) level of 2.5 pg/mL (normal: 10-65 pg/mL), undetectable PTH-related peptide level, normal 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 36 ng/mL (normal: 14-60 ng/mL), and elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 level of 106 pg/mL (normal: 25-45 pg/mL).

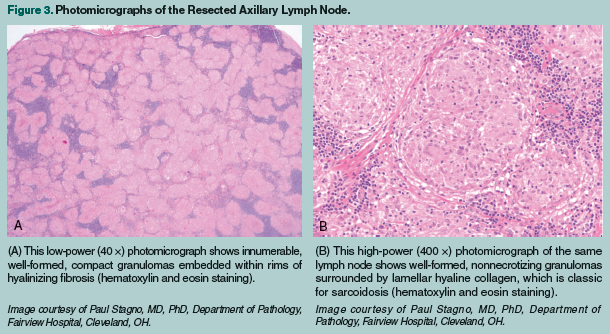

The hypercalcemia responded quickly to infusions of intravenous (IV) normal saline, IV zoledronic acid, and subcutaneous calcitonin. Her vitamin D3 was discontinued. Within 48 hours, the patient’s blood pressure and serum chemistries, including serum calcium, normalized, and she became lucid and returned to her baseline state of mental functioning. Initially, the clinically suspected diagnosis was an occult underlying malignancy, most likely lymphoma, based on her known celiac disease and the presence of generalized lymphadenopathy. CT scans of the patient’s lungs revealed bilateral, upper-lobe predominant, bronchovascular nodules with associated bilateral hilar and paratracheal adenopathies (Figure 1). CT imaging of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis showed lymphadenopathy throughout the retroperitoneum and celiac regions, with prominent mesenteric lymph nodes (Figure 2). Excisional biopsies of the left axillary and mesenteric lymph nodes revealed nonnecrotizing granulomas in both specimens, consistent with granulomatous lymphadenitis (Figures 3A and 3B).

The initial in-hospital pulmonary consultant doubted that the patient had sarcoidosis even though it was on his differential diagnosis, and the patient was discharged. However, a second pulmonologist consulted after the patient’s discharge from the hospital determined that she indeed met the criteria for sarcoidosis; this assessment was based on the constellation of clinical, radiographic, and pathologic findings. The second pulmonologist initiated oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg twice daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. At the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improved energy levels and mood, with markedly less back pain. Her serum calcium levels have remained normal.

NEXT: Discussion

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory granulomatous disease of unknown cause, with pulmonary involvement seen in more than 90% of patients with the disease.1,2 Extrapulmonary manifestations most commonly affect the extrathoracic lymph nodes, eyes, skin, and joints.1,3 Subcutaneous sarcoidosis is found in up to 12% of cutaneous disease as an early initial presentation of sarcoidosis.4 According to the American Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society, and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is established when clinical and radiologic findings are supported by the histologic evidence of nonnecrotizing granulomas, and when other conditions that can produce similar pathology are excluded.2

Although the etiology of sarcoidosis is still unknown, two parallel avenues of genetic and environmental investigation support the hypothesis that sarcoidosis development depends on an appropriate environmental exposure in a genetically susceptible host.5 Findings of a study published in 2007 revealed that immune characteristics of celiac disease may be associated with an increased risk of developing sarcoidosis.6 Sarcoidosis shows a predilection for persons who are younger than 40 years of age, and typically peaks between the second and third decades of life.2,7 There has been a second peak incidence reported in Scandinavian countries and in Japan in women over age 50 years.2,8 Although many patients with sarcoidosis live with the disease through their later years, few are newly diagnosed after the age of 65 years. This was shown in a retrospective series by Stadnyk et al,9 who reviewed new cases of biopsy-proven sarcoidosis over a 35-year period and found that only 7.8% occurred in elderly patients.

Making the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in the elderly (≥70 years) is often difficult and lengthy because clinical presentations are usually atypical in this population.10,11 In a retrospective case series examining sarcoidosis diagnosed in persons over 70 years of age, Chevalet and colleagues11 noted that an alteration of general health with asthenia, anorexia, or weight loss was the most frequent clinical presentation of the disease, even though intrathoracic organs were most commonly involved. Additionally, because elderly patients also present with characteristic symptoms of pulmonary and multisystem disease, sarcoidosis should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of these disorders.12 Not surprisingly, there was a long interval for most of the cases described by Chevalet et al11 (mean, 31.2 months) before essential evidence was established for a diagnosis of the disease.

Chest radiographs also display atypical patterns in elderly patients including mediastinal adenopathy alone or in combination with unilateral hilar adenopathy, solitary or multiple pulmonary masses, and atelectasis—features that are distinct from the salient characteristics, such as bilateral hilar adenopathy, described in younger patients.13,14 A rise in serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels is not an efficient diagnostic tool in elderly patients because of the increased frequency of renal insufficiency and diabetes mellitus in this population, which tend to increase ACE levels.2,15 In addition, elevated ACE levels are not specific for sarcoidosis because mild elevations can be seen in many intra- and extrathoracic diseases.16

In addition to an elevated serum ACE level, several other nonspecific laboratory abnormalities have been noted in patients with sarcoidosis, including hypergammaglobulinemia, cutaneous anergy suggestive of impaired lymphocyte responses to recall antigens, and peripheral lymphopenia.1,2,17 Hypercalcemia occurs in approximately 5% of patients with sarcoidosis, although hypercalciuria is 3 times more frequent.3,18,19 These abnormalities of calcium metabolism are due to the dysregulated production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by activated lymphocytes and macrophages within granulomas, and gamma-interferon produced by these cells is thought to play a major role in the aberrant synthesis of this vitamin.3,17 A case report published in 2007 found that hypercalcemia can occur in persons with granulomatous disorders such as sarcoidosis in the setting of unusually normal (ie, not elevated) levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, with dehydration, increased uptake of oral calcium, or decreased calcium excretion, especially in those with mild renal insufficiency, being contributing factors.20 In normal subjects, there has been no increase in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2 levels claimed after oral administration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D at high doses; however, there has been a substrate-product relationship reported in older persons and in persons with sarcoidosis, renal failure, and primary hyperparathyroidism, among others.21 Elevation in plasma PTH and vitamin D3 by primary hyperparathyroidism and sarcoidosis, respectively, has an additive effect on the regulation of serum calcium level.22 Undetected persistent hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria can cause nephrocalcinosis, predispose affected patients to symptomatic renal stone disease, and may even progress toward renal failure.2,23,24

Because the histologic evidence of nonnecrotizing granulomas is usually necessary to make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, biopsies directed at morphologic or clinical abnormalities usually provide the highest yield.11,17 Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies should be considered only when there is radiographic evidence of intrathoracic involvement, as routine biopsies of the lungs in the elderly are less definitive.11 However, bronchoalveolar lavage with flow cytometric evaluation of the effluent may be considered even when there is no intrathoracic involvement on chest radiographs.11,25 It is not uncommon for the elderly patient with sarcoidosis to undergo 2 or more biopsy procedures,10 as seen in the case patient discussed in this article. This is because sarcoidosis is indeed rare in these patients, and before it is established, a local sarcoid-like reaction that occurs with malignancies should be excluded.9,26 It is important to appreciate that such sarcoid-like reactions within the draining lymph nodes can occur in approximately 4% of carcinomas, nearly 14% of cases of Hodgkin’s disease, and approximately 7% of cases of non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and must be distinguished from multisystem sarcoidosis.26,27 Histopathologically, the granulomas in these sarcoid-like reactions are usually not uniform, showing areas of marked proliferations of epithelioid or giant cells; they may contain fibrinoid exudates or display areas of necrosis, but some of them can demonstrate features typical of sarcoidosis.27

Once established, the disease course of sarcoidosis in the elderly is generally similar to that of younger subjects.11,28 It is not always easy to control; however, results have generally been satisfactory with the use of oral corticosteroid therapy.10,11 Although most patients stabilize or improve with treatment, relapses occur more frequently in the elderly.29Treatment complications in the elderly have been difficult to ascertain, but based on available evidence, seem to be mainly infectious in nature.11 Although oral corticosteroid therapy is associated with disease control in more than 80% of elderly patients, their use must be balanced with the significant toxicities associated with these agents.11 In addition to infections, side effects of oral corticosteroids relevant to the elderly include ocular cataracts, accelerated atherosclerosis with ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular consequences, gastritis with ulcer formation, hypertension, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus.30,31 Several cytotoxic steroid-sparing agents have been used to treat sarcoidosis.32 While these agents clearly are of value in selected patients, no studies have clearly delineated when these drugs should be used or specifically defined their safety and efficacy in certain cohorts of patients.1,17 Therefore, monitoring for symptoms of drug toxicity is essential, and prevention of modifiable risk factors should be addressed in elderly patients taking long-term oral corticosteroid therapy.10

Conclusion

This case of sarcoidosis in an octogenarian illustrates the difficulty of diagnosing rarer conditions with nonspecific presentations that affect multiple organ systems. While sarcoidosis is typically diagnosed in young adults, it can indeed manifest in older patients. Identification of this disorder is important because available treatments lead to improvement or stabilization of the disease in more than 80% of elderly persons.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Paul Stagno, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology, Fairview Hospital, Cleveland, OH, for providing the microscopic pathology images, and Craig Irish, MD, Department of Radiology, Fairview Hospital, for providing the radiographic images.

Dr. Jamie was a Resident Physician in Family Medicine, Fairview Hospital/Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency at the time of this submission; she is now a Fellow, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; Dr. Tyler is Coordinator of Geriatric Education and Research, Fairview Hospital/Cleveland Clinic Family Medicine Residency, and Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH; and Dr. Parambil is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH.

References

- Wu JJ, Schiff KR. Sarcoidosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(2):312-322.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee. February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(2):736-755.

- Holmes J, Lazarus A. Sarcoidosis: extrathoracic manifestations. Dis Mon. 2009;55(11):675-692.

- Shigemitsu H, Yarbrough C, Prakash S, Sharma O. A 65-year-old woman with subcutaneous nodule and hilar adenopathy. Chest. 2008;134(5):1080-1083.

- Culver DA, Newman LS, Kavuru MS. Gene-environment interactions in sarcoidosis: challenge and opportunity. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(3):267-275.

- Ludvigsson JF, Wahlstron J, Grunewald J, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2007;24(2):121-126.

- Gordis L. Sarcoidosis. In: Epidemiology of Chronic Lung Diseases in Children. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1973:53-78.

- Alsbirk PH. Epidemiologic studies on sarcoidosis in Denmark based on a nationwide central register. A preliminary report. Acta Med Scand. 1964;176(suppl 425):106-109.

- Stadnyk AN, Rubinstein I, Grossman RF, et al. Clinical features of sarcoidosis in elderly patients. Sarcoidosis. 1988;5(2):121-123.

- Margolis ML, Israel HL. Sarcoidosis in older patients—clinical characteristics and course. Geriatrics. 1983;38(1):121-123, 128.

- Chevalet P, Clément R, Rodat O, Moreau A, Brisseau JM, Clarke JP. Sarcoidosis diagnosed in elderly subjects: retrospective study of 30 cases. Chest. 2004;126(5):1423-1430.

- Alhamad EH, Alanezi MO, Idrees MM, et al. Clinical characteristics and computed tomography findings in Arab patients diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(6):454-459.

- Conant EF, Glickstein MF, Mahar P, Miller WT. Pulmonary sarcoidosis in the older patient: conventional radiographic features. Radiology. 1988;169(2):315-319.

- Nunes H, Brillet PY, Valeyre D, Brauner MW, Wells AU. Imaging in sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(1):102-120.

- Lieberman J, Sastre A. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme: elevations in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(6):825-826.

- Allen RK. A review of angiotensin converting enzyme in health and disease. Sarcoidosis. 1991;8(2):95-100.

- Belfer MH, Stevens RW. Sarcoidosis: a primary care review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(9):2041-2050, 2055-2056.

- Rizzato G. Clinical impact of bone and calcium metabolism changes in sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1998;53(5):425-429.

- Goldstein RA, Israel HL, Becker KL, Moore CF. The infrequency of hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 1971;51(1):21-30.

- Falk S, Kratzsch J, Paschke R, Koch CA. Hypercalcemia as a result of sarcoidosis with normal serum concentrations of vitamin D. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(11):133-136.

- Bevilacqua M, Dominguez LJ, Gandolini G, et al. Vitamin D substrate-product relationship in idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;113(1-2):3-8.

- Yoshida T, Iwasaki Y, Kagawa T, et al. Coexisting primary hyperparathyroidism and sarcoidosis in a patient with severe hypercalcemia. Endocr J. 2008;55(2):391-395.

- Asakura K. Renal involvement in sarcoidosis. Intern Med. 2002;41(12):1088-1089.

- Rizzato G, Colombo P. Nephrolithiasis as a presenting feature of chronic sarcoidosis: a prospective study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1996;13(2):167-172.

- Chapman JT, Mehta AC. Bronchoscopy in sarcoidosis: diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9(5):402-407.

- de Hemricourt E, De Boeck K, Hilte F, et al. Sarcoidosis and sarcoid-like reaction following Hodgkin’s disease. Mol Imaging Biol. 2003;5(1):15-19.

- Brincker H. Sarcoid reactions in malignant tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 1986;13(3):147-156.

- Lenner R, Schilero GJ, Padilla ML, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis presenting in patients older than 50 years. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2002;19(2):143-147.

- Hunninghake GW, Gilbert S, Pueringer R, et al. Outcome of the treatment for sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(4 pt 1):893-898.

- Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison, J et al. Population-based assessment of adverse events associated with long-term glucocorticoid use. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(3):420-426.

- Boumpas DT, Chrousos GP, Wilder RL, Cupps TR, Balow JE. Glucocorticoid therapy for immune-mediated diseases: basic and clinical correlates. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(2):1198-1208.

- Lynch JP 3rd, McCune WJ. Immunosuppressive and cytotoxic pharmacotherapy for pulmonary disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(2):395-420.