A Review of Diaper Dermatitis: Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Management

ABSTRACT: While most eruptions in the diaper area are secondary to an irritant contact dermatitis, the differential diagnosis of diaper dermatitis includes many other inflammatory and infectious skin conditions. It is important to consider a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating an infant with diaper dermatitis. Severe or recalcitrant presentations may suggest a serious underlying systemic disease, such as zinc deficiency or Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Clues to correct diagnosis include morphology and distribution of lesions in the diaper area, cutaneous involvement of other body sites, and systemic manifestations. This article reviews the clinical features, diagnosis, and management of the various types of diaper dermatitis.

Diaper dermatitis is a general term that refers to an inflammatory skin eruption in the diaper area. It is the most common dermatologic disorder of infancy, accounting for 1 million outpatient visits per year.1

An estimated 25% of infants are affected with diaper dermatitis at any given time, with peak incidence occurring at 9 to 12 months of age.1,2 With greater than 90% of cases being managed in primary care,1 it is critical that providers in this setting receive proper education in the diagnosis and management of diaper dermatitis.

Irritant Contact Diaper Dermatitis

Irritant contact diaper dermatitis (ICDD) is the most common cause of diaper dermatitis. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial. The moist environment created by chronic occlusion and urine retention causes maceration of the skin, disrupting its barrier function and subsequently increasing its permeability to local irritants and microorganisms. Furthermore, maceration makes the skin more susceptible to frictional injury from contact with the diaper.3 Retained urine and feces in the diaper area work synergistically to further damage macerated skin. As a result, the risk of diaper dermatitis is much higher in infants with diarrhea.

Fecal urease-producing microorganisms break down urea in urine to release ammonia, which increases the pH. The higher pH stimulates fecal proteases and lipases that cause skin breakdown.4,5 Furthermore, the abnormal pH promotes the growth of microorganisms, including Candida, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.6 The lower stool pH in breastfed infants may explain their lower incidence of diaper dermatitis compared with formula-fed infants.2,7,8

ICDD affects the convex surfaces that are in direct contact with the diaper, including the buttocks, thighs, lower abdomen, and genitalia, with sparing of the skin folds. It presents as shiny, erythematous patches and plaques with or without scale (Figure 1).9-11

Figure 1. Irritant contact diaper dermatitis, featuring erythematous patches on the mons pubis, scrotum, and medial thighs with sparing of the inguinal creases.

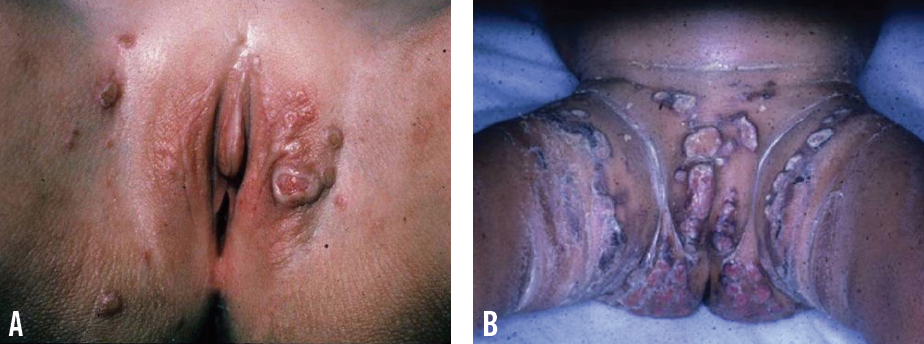

Granuloma gluteale infantum (GGI) and Jacquet erosive dermatitis are severe variants of ICDD. GGI features numerous, asymptomatic, violaceous or reddish brown papules and nodules that range in size from 0.5 cm to 4 cm. Lesions are located on the convexities and run parallel to the skin folds. Many factors have been proposed in its pathogenesis, including longstanding ICDD, high-potency fluorinated topical corticosteroids, and Candida infection.10-12 Jacquet erosive dermatitis is a severe form of ICDD characterized by well-demarcated erosions and punched-out ulcers with elevated margins (Figure 2).10,13 It occurs in the setting of urinary incontinence, diarrhea, and infrequent diaper changes.14,15

Figure 2. Jacquet erosive dermatitis, featuring discrete, ulcerated, reddish purple nodules on the vulva and inguinal creases (A) and welldemarcated, erythematous plaques with erosions and punched-out ulcers on the convexities (B).

Management and prevention focuses on keeping the skin as dry as possible, avoiding prolonged occlusion, and minimizing contact with urine and feces. This is accomplished with frequent diaper changes, superabsorbent disposable diapers, topical barrier agents, and appropriate skin care.

Diapers should be changed every 3 to 4 hours or as soon as soiling occurs.8,16 If feasible, we recommend letting the skin air-dry by leaving the diaper off for as long as possible after the infant has urinated or defecated. It is also beneficial to let the infant sleep with the diaper left open. Drying the diaper area with a hair dryer, however, should be avoided, because it can result in chapping or burns.8,17

Superabsorbent disposable diapers have an absorbent gelling material in their core, which allows them to absorb fluid many times their weight. This minimizes skin wetness and prevents the mixing of urine and feces. Additionally, the buffering capacity of these diapers maintains the skin’s normal pH.18,19 Recent advances in superabsorbent disposable diapers have further reduced the incidence and severity of diaper dermatitis. The addition of a “breathable” outer diaper cover that is permeable to air and water vapor but impermeable to liquid has been shown to decrease the incidence of irritant and candidal diaper dermatitis.20 Moreover, a novel superabsorbent disposable diaper has been engineered to continuously deliver a petrolatum and zinc oxide based formulation to the skin.21

Over-the-counter barrier pastes and ointments containing zinc oxide and/or petrolatum protect the skin from urine and feces by creating an impermeable barrier and promoting recovery of the skin’s natural barrier.10 These should be applied liberally with diaper changes and after bathing.8,16

The diaper area should be cleansed gently with lukewarm water with each diaper change. If soap is necessary (eg, to remove feces), a mild fragrance-free soap can be used. Nevertheless, because even mild soaps can be irritating, we recommend limiting their use. Scrubbing and harsh soap should be avoided, because they can further damage the skin.8,17 While older baby wipes containing alcohol caused skin irritation, modern baby wipes that are nonwoven and free of alcohol are generally well-tolerated.8,16,22 We believe that plain water is preferable to baby wipes for cleaning the diaper area, but in situations in which water alone is not an option, parents should choose wipes that are free of fragrances and preservatives to avoid allergic sensitization.

Although mild cases of ICDD can resolve with the prevention strategies discussed here, moderate to severe cases may require the addition of a low-potency topical corticosteroid such as 1% hydrocortisone. The corticosteroid should be applied 2 times per day during diaper changes for 2 weeks.8,16 If a secondary candidal infection is suspected, it should be treated as well.

Combination agents containing mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids (eg, combination nystatin and triamcinolone, combination clotrimazole and betamethasone dipropionate) commonly are prescribed by primary care providers for diaper dermatitis.1 These agents must be avoided due to the risk of skin atrophy, striae, GGI, and systemic absorption when mid- to high-potency corticosteroids are applied to the thin skin of the diaper area under occlusion.8

Candidal Diaper Dermatitis

Superimposed Candida infection is the most common complication of untreated ICDD. Approximately 40% to 75% of children with diaper rashes lasting longer than 3 days are colonized with Candida albicans.6 The moist, warm environment of the diaper area in the setting of increased pH and disrupted skin barrier lead to yeast overgrowth and infection. The source of Candida is the infant’s gastrointestinal tract; thus, risk factors for candidal diaper dermatitis include diarrhea and recent antibiotic use, which alters gut flora.

Patients present with discrete papules and pustules that coalesce into beefy red plaques with peripheral scale and satellite lesions. Involvement of the skin folds and the presence of satellite papules and pustules distinguish candidal diaper dermatitis from ICDD (Figure 3). The oral cavity should be inspected for the presence of thrush. Persistent or recurrent candidal diaper dermatitis may be a sign of diabetes mellitus type 1 or immune deficiency.

Figure 3. Candidal diaper dermatitis, featuring erythematous papules that coalesce into beefy red plaques with satellite papules and pustules and peripheral scale on the convexities and skin folds.

The diagnosis is generally clinical and can be confirmed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation testing of the peripheral scale or a pustule demonstrating pseudohyphae and spores. Treatment is the same as for ICDD but with the addition of a topical antifungal such as nystatin, miconazole, ketoconazole, or clotrimazole applied 2 times per day with diaper changes. Oral nystatin may be used if there is concurrent thrush or if candidal diaper dermatitis is recurrent. A low-potency topical corticosteroid may be added to decrease inflammation.9-11

Allergic Contact Diaper Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is uncommon in the diaper area. The allergy is typically to the rubber components found in the elastic sidebands used to secure the diaper. As a result, this dermatitis has been called “Lucky Luke” or “cowboy holster” dermatitis, because it affects the lateral buttocks and hips in a distribution reminiscent of a cowboy’s gun belt holster (Figure 4).10,23

Figure 4. Allergic contact diaper dermatitis with erythema in the distribution of a cowboy’s gun belt holster.

Disperse dyes in diapers also have been implicated as allergens inducing a contact dermatitis.24 The lesions of ACD are pruritic, scaly, erythematous papules and plaques with vesicles. It often is difficult to clinically distinguish ICDD from ACD. Patch testing can be used to determine which allergens the infant is allergic to. Treatment is with avoidance of the allergen and application of a low-potency topical corticosteroid.10,23

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis most commonly begins between 3 weeks to 3 months of age. It is characterized by erythematous papules and plaques with greasy, yellow scale on the scalp (“cradle cap”), eyebrows, nasolabial folds, retroauricular areas, trunk, flexures, intertriginous areas, and diaper area. Due to the moist environment of the diaper and intertriginous areas, lesions in these locations often lack the greasy scale and have a glistening, erythematous appearance (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Seborrheic dermatitis, featuring erythematous patches on the face, trunk, flexures, and diaper area with extensive involvement of the skin folds.

In the diaper area, seborrheic dermatitis involves the skin folds but, unlike with candidal dermatitis, pustules and satellite lesions are not seen. Treatment is with a low-potency topical corticosteroid applied 2 times per day with diaper changes with or without a topical azole.9-11

Napkin Psoriasis

Psoriasis involving the diaper area is also known as napkin psoriasis. While psoriasis overall is uncommon in infants, the diaper area is the site most commonly affected due to repetitive irritation from the diaper, urine, and feces (ie, Koebner phenomenon).8 The peak age of incidence is 6 to 18 months. Napkin psoriasis is characterized by well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques that involve the skin folds (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Napkin psoriasis, featuring well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with satellite lesions and involvement of the folds (A). Note the linear arrangement of lesions on the lower abdomen (B), illustrating the Koebner phenomenon.

As with seborrheic dermatitis, the classic scale (silvery white in psoriasis) usually is absent in the diaper and intertriginous areas due to the moist environment.8-10,25 Like candidal diaper dermatitis, napkin psoriasis can have satellite papules, but pustules are absent. Clues to the diagnosis include a family history of psoriasis, possible nail changes, and the presence of psoriatic lesions with the classic silvery white scale in other areas of the body. Psoriasis often is resistant to 1% hydrocortisone, requiring more potent topical corticosteroids such as 2.5% hydrocortisone or 0.05% desonide.8-10,25

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) presents in the first year of life. The diaper area usually is not affected, because the moist environment protects against a primary eczematous eruption and environmental allergens. Nevertheless, infants with AD still can develop ICDD or ACD. AD generally affects the face (particularly the cheeks), trunk, and extensors of the extremities in infants. There may be a family history of AD, asthma, or allergic rhinitis.

In the rare cases in which AD involves the diaper area, an acute dermatitis with excoriations or chronic lichenification is seen. Secondary infection with Staphylococcus aureus is a frequent complication. Treatment is with low-potency topical corticosteroids and emollients. An oral antistaphylococcal agent, such as cephalexin or dicloxacillin, may be necessary if signs of infection are present.9-11

Bacterial Infections

Impetigo is a superficial skin infection most commonly caused by S aureus.26 The nonbullous form is more common and is characterized by 1 to 2 mm papules and vesicles that progress to pustules, which subsequently rupture to leave a thick, honey-colored crust. Due to the moisture in the diaper area, this crust may be absent, leaving only superficial erosions.

The bullous form is caused by a specific strain of S aureus that produces the exfoliative toxin. It presents as large, flaccid, turbid bullae that easily rupture to leave erosions (Figure 7).9,26 Diagnosis of impetigo is generally clinical but can be confirmed with culture of a pustule or blister. Localized bullous and nonbullous impetigo can be treated with mupirocin 2% ointment, reserving oral antibiotics for widespread or complicated cases.8

Figure 7. Bullous impetigo, featuring discrete, turbid bullae on the buttocks and thighs.

Perianal cellulitis is caused primarily by group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, although a recent study has shown a possible shift to S aureus as the causative agent.27 The infection is characterized by tender, brightly erythematous perianal skin, possibly with fissures (Figure 8). Patients can have associated pruritus, pain with defecation, and blood-streaked stools. A positive culture test result confirms the diagnosis. Treatment is with oral antibiotics directed against the cultured agent, along with mupirocin 2% ointment.28

Figure 8. The shiny, brightly erythematous skin of perianal cellulitis.

Viral Infections

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in neonates is due to vertical transmission from genital lesions in the mother. Infection most commonly is with HSV-2 and presents as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base with ulcerations.11,13 In older infants, anogenital HSV should raise suspicion for child abuse.11 Tzanck smear, direct fluorescent antibody testing, and viral polymerase chain reaction testing of scrapings taken from the base of a vesicle are used for diagnosis.13 Due to the risk of disseminated disease, especially to the central nervous system, neonates with suspected HSV infection should be given intravenous acyclovir while waiting for confirmatory test results. This is followed by suppression therapy with oral acyclovir for 6 months.29

Human papillomavirus infection of the anogenital region (ie, condyloma acuminata or genital warts) presents as flesh-colored to pink, verrucous papules and nodules (Figure 9). In children younger than 3 years of age, infection is most commonly due to vertical transmission from the mother. Sexual abuse should be considered in all young children, especially those older than 3 years of age.10

Figure 9. Anal warts, featuring pink, verrucous papules and plaques on the perianal skin.

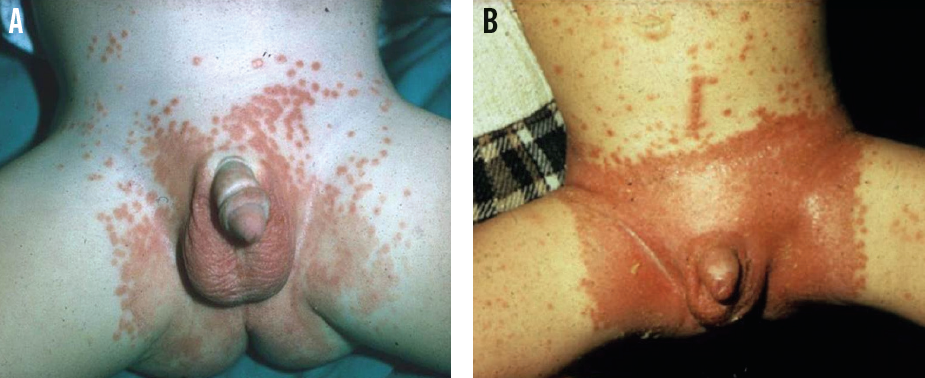

Molluscum contagiosum presents as discrete, flesh-colored to pink, dome-shaped papules with central umbilication (Figure 10). It can occur anywhere on the body, including the diaper area. In a subset of patients, primarily those with atopy, a perilesional eczematous reaction may occur.10

Figure 10. The pink, dome-shaped papules of molluscum contagiosum on the scrotum and medial thighs.

Diagnosis of genital warts and molluscum contagiosum is clinical. These infections resolve after months to years on their own, making the decision to treat optional. Generally, warts and molluscum can be treated with topical agents such as imiquimod 5% cream or podofilox 0.05% gel, or by destructive methods such as cryotherapy, laser ablation, and electrodessication.30,31

Many other topical agents have been used to treat molluscum, including salicylic acid, topical retinoids, and cantharidin.11 In the diaper area, however, the use of any of these topical agents can be fraught with complications. Similarly, destructive methods tend to be painful and are best avoided in infants and young children. Consequently, we recommend expectant management and that parents be reassured about the benign and self-limited nature of these infections.

Lichen Sclerosus

Children younger than 13 years of age account for 15% of cases of lichen sclerosus (LS), but occurrence during infancy is uncommon.10,11,32 LS has a female predominance and presents as shiny, atrophic, ivory colored patches and plaques in the anogenital region (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Lichen sclerosus, featuring an atrophic, white, sclerotic patch on the vulva. Note the fissures in the interlabial sulci and obliteration of the labia minora.

Involvement of the vulvar and anal openings creates the classic “figure of eight” appearance. Occasional findings include erosions, fissures, and hemorrhagic bullae. Patients may have pruritus, vulvar and/or rectal bleeding, pain, and constipation.

If left untreated, LS may result in scarring, adhesions, and atrophy with obliteration of anogenital structures.10,11 In uncircumcised boys, LS may affect the tip of the foreskin, leading to phimosis (inability to retract the foreskin) and, less commonly, urethral stenosis with urinary obstruction.

Diagnosis is generally clinical, although skin biopsy is confirmatory.10,11,33 Treatment with a 6- to 8-week course of high-potency topical corticosteroids, such as betamethasone, is effective in children with LS, but close follow-up is necessary.10,11,34

Zinc Deficiency

Zinc deficiency presents as well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaques that can evolve into crusted and eroded vesiculobullous and pustular lesions affecting the perineal, perioral, and acral areas (Figure 12). There is associated failure to thrive, developmental delay, diarrhea, and alopecia.13,16

Figure 12. Acrodermatitis enteropathica, featuring erythema with erosions, bullae, and peripheral hemorrhagic crust on the hands, feet, and genital area.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a hereditary form of zinc deficiency caused by an autosomal recessive defect in the intestinal zinc-binding ligands, which leads to zinc malabsorption. Other causes of zinc deficiency include prematurity, low levels of zinc in maternal breast milk, malabsorption syndromes, and prolonged parenteral nutrition without zinc supplementation.9-11,13 Diagnosis is confirmed by a low serum zinc level; however, a normal level does not exclude zinc deficiency. Treatment with oral zinc supplementation provides rapid improvement.11

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare but possibly life-threatening hematologic disorder with peak incidence at 1 year of age.13 Experts disagree as to whether it is a reactive or neoplastic process.35 Cutaneous lesions present as yellowish brown, scaly papules and plaques, often with petechiae, purpura, atrophy, erosions, and/or ulcerations (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, featuring discrete, hemorrhagic papules and petechiae on the lower abdomen and inguinal folds (A), and erosive erythema on the labia (B). LCH also may feature yellow-brown, erythematous papules and plaques with overlying crust on the scalp (C).

The distribution of lesions is similar to that of seborrheic dermatitis, affecting the scalp, retroauricular, diaper area, and intertriginous areas.9,13 As a result, LCH should be considered in patients with what appears to be recalcitrant seborrheic dermatitis. In the diaper area, LCH affects the folds, genitalia, and perianal region.9

Additional findings in cases of LCH include lytic bone lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and, less commonly, pulmonary or central nervous system involvement.35 Diagnosis is made via skin biopsy. Cutaneous LCH is treated with topical nitrogen mustard, and systemic chemotherapy is necessary for internal organ involvement.10,11,35

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease (KD), also called mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, is an acute febrile systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology. KD is most common in Japanese children younger than 5 years of age and has a peak incidence from 6 to 11 months.36

The disease presents with prolonged fever, conjunctivitis, oropharyngeal changes, cervical lymphadenopathy (usually unilateral and greater than 1.5 cm), rash, and peripheral extremity changes. The conjunctivitis is bilateral and nonexudative, predominantly involving the bulbar conjunctivae with sparing of the limbus. Oropharyngeal changes include erythema, fissuring or cracking of the lips, diffuse erythema of the oropharynx, and/or a “strawberry tongue.”36

The rash in KD first involves the diaper area, where it presents as an erythematous, desquamating eruption. It then generalizes to the trunk and extremities as a widespread polymorphous exanthem.10 Additionally, KD has been reported to trigger a psoriasiform skin eruption in children without previous history of psoriasis.37,38 Peripheral extremity changes include erythema of the palms and soles and indurated edema of the hands and feet, followed by periungual desquamation after 1 to 2 weeks.36

The most feared complications of KD are coronary artery aneurysms, which develop in 20% of untreated patients, typically 1 to 2 weeks after the onset of fever. Consequently, all patients with KD should be evaluated with echocardiography at the time of diagnosis, at 2 weeks, and at 6 to 8 weeks after disease onset.

In addition to coronary artery aneurysms, patients with KD may develop myocarditis, pericarditis, valvular involvement, arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure.36

Other possible systemic findings include arthralgia or arthritis, aseptic meningitis, anterior uveitis, gastrointestinal disturbance, urethritis, and hydrops of the gallbladder.36

Diagnosis of KD is made clinically based on established diagnostic criteria. The patient must have unexplained fever for 5 or more days and at least 4 of 5 other specific features (Table). It is important to exclude other diseases with similar findings, including infections, rheumatologic conditions, and drug reactions.10,36

Treatment is with 2 g/kg of intravenous immunoglobulin and high-dose aspirin at 80 to 100 mg/kg/d within 10 days of the onset of fever. This combination has been shown to substantially decrease the prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms. Aspirin is decreased to a maintenance dose of 3 to 5 mg/kg/d once the patient has been afebrile for 48 to 72 hours. This low-dose aspirin can be discontinued if the patient has a normal echocardiogram after 6 to 8 weeks.36 n

Julia G. Gosis, MD, is a graduate of the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville.

Amy L. Gagnon, MD, is a resident physician in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Kenneth E. Greer, MD, is a professor in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Barbara B. Wilson, MD, is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

1. Ward DB, Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Krowchuk DP. Characterization of diaper dermatitis in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(9):943-946.

2. Jordan WE, Lawson KD, Berg RW, Franxman JJ, Marrer AM. Diaper dermatitis: frequency and severity among a general infant population. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3(3):198-207.

3. Berg RW. Etiology and pathophysiology of diaper dermatitis. Adv Dermatol. 1988;3:75-79.

4. Berg RW, Buckingham KW, Stewart RL. Etiologic factors in diaper dermatitis: the role of urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3(2):102-106.

5. Buckingham KW, Berg RW. Etiologic factors in diaper dermatitis: the role of feces. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3(2):107-112.

6. Leyden JJ, Kligman AM. The role of microorganisms in diaper dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(1):56-59.

7. Prasad HR, Srivastava P, Verma KK. Diaper dermatitis—an overview. Ind J Pediatr. 2003;70(8):635-637.

8. Shin HT. Diaper dermatitis that does not quit. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(2):124-135.

9. Singalavanija S, Frieden IJ. Diaper dermatitis. Pediatr Rev. 1995;16(4):142-147.

10. Camilleri MJ, Calobrisi SD. Skin eruptions in the diaper area. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1999;11(6):211-244.

11. Ravanfar P, Wallace JS, Pace NC. Diaper dermatitis: a review and update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24(4):472-479.

12. Bluestein J, Furner BB, Phillips D. Granuloma gluteale infantum: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1990;7(3):196-198.

13. Halbert AR, Chan JJ. Anogenital and buttock ulceration in infancy. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43(1):1-8.

14. Rodriguez-Poblador J, González-Castro U, Herranz-Martínez S, Luelmo-Aguilar J. Jacquet erosive diaper dermatitis after surgery for Hirschsprung disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(1):46-47.

15. Hara M, Watanabe M, Tagami H. Jacquet erosive diaper dermatitis in a young girl with urinary incontinence. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8(2):160-161.

16. Humphrey S, Bergman JN, Au S. Practical management strategies for diaper dermatitis. Skin Therapy Lett. 2006;11(7):1-6.

17. Boiko S. Treatment of diaper dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 1999;17(1):235-240.

18. Campbell RL, Seymour JL, Stone LC, Milligan MC. Clinical studies with disposable diapers containing absorbent gelling materials: evaluation of effects on infant skin condition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17(6):978-987.

19. Lane AT, Rehder PA, Helm K. Evaluations of diapers containing absorbent gelling material with conventional disposable diapers in newborn infants. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144(3):315-318.

20. Akin F, Spraker M, Aly R, Leyden J, Raynor W, Landin W. Effects of breathable disposable diapers: reduced prevalence of Candida and common diaper dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18(4):282-290.

21. Baldwin S, Odio MR, Haines SL, O’Connor RJ, Englehart JS, Lane AT. Skin benefits from continuous topical administration of a zinc oxide/petrolatum formulation by a novel disposal diaper. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(suppl 1):5-11.

22. Ehretsmann C, Schaefer P, Adam R. Cutaneous tolerance of baby wipes by infants with atopic dermatitis, and comparison of the mildness of baby wipe and water in infant skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(suppl 1):16-21.

23. Roul S, Ducombs G, Leaute-Labreze C, Taïeb A. “Lucky Luke” contact dermatitis due to rubber components of diapers. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38(6):363-364.

24. Alberta L, Sweeney SM, Wiss K. Diaper dye dermatitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e450-e452.

25. Busch AL, Landau JM, Moody MN, Goldberg LH. Pediatric psoriasis. Skin Therapy Lett. 2012;17(1):4-7.

26. Hedrick J. Acute bacterial skin infections in pediatric medicine: current issues in presentation and treatment. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5(suppl 1):35-46.

27. Heath C, Desai N, Silverberg NB. Recent microbiological shifts in perianal bacterial dermatitis: Staphylococcus aureus predominance. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(6):696-700.

28. Kokx NP, Comstock JA, Facklam RR. Streptococcal perianal disease in children. Pediatrics. 1987;80(5):659-663.

29. Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ, Wan W, et al; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Oral acyclovir suppression and neurodevelopment after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(14):1284-1292.

30. Moresi JM, Herbert CR, Cohen BA. Treatment of anogenital warts in children with topical 0.05% podofilox gel and 5% imiquimod cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18(5):448-450.

31. Hanna D, Hatami A, Powell J, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the efficacy and adverse effects of four recognized treatments of molluscum contagiosum in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):574-579.

32. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(5):803-806.

33. Clouston D, Hall A, Lawrentschuk N. Penile lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans). BJU Int. 2011;108(suppl 2):14-19.

34. Fischer G, Rogers M. Treatment of childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus with potent topical corticosteroid. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14(3):235-238.

35. Abla O, Egeler RM, Weitzman S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: current concepts and treatments. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):354-359.

36. Scuccimarri R. Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59(2):425-445.

37. Eberhard BA, Sundel RP, Newburger JW et al. Psoriatic eruption in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2000;137(4):578-580.

38. Ergin S, Karaduman A, Demirkaya E, Bakkaloğlu A, Özkaya Ö. Plaque psoriasis induced after Kawasaki disease. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51(4):375-377.