Reducing the Inappropriate Prescribing of Antibiotics for Rhinosinusitis

ABSTRACT: The inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics for symptoms of rhinosinusitis is prevalent in the United States. A survey was conducted to explore the difference in perceptions about expectations for an antibiotic prescription between patients presenting with rhinosinusitis symptoms to urgent care clinics and the health care providers at the clinics. When urgent care providers were surveyed, 100% of them believed that patients with sinusitis symptoms expected antibiotics. In the same setting, a survey was given to adult patients presenting with symptoms of sinusitis asking whether they thought antibiotics were needed that day. Of these patients, 76% believed that they needed an antibiotic for the symptoms they reported. The difference in expectations about antibiotic prescriptions shows a potential area for providers to improve practice by reducing the inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics.

KEYWORDS: Sinusitis, antibiotics, overprescribing, acute bacterial rhinosinusitis, bacterial resistance, patient perception, prescriber perception

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) affects 1 in 7 adults in the United States, resulting in approximately 31 million individuals receiving the diagnosis each year.1 The annual cost of treatment for ABRS in the United States is approximately $2 billion.2 The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey lists sinusitis as the fifth most common U.S. diagnosis for which an antibiotic is prescribed.3 The problem is not limited to the United States—for example, researchers in the Netherlands found that general practitioners overestimate upper respiratory symptoms and patients’ expectations when prescribing antibiotic therapy in primary care.4 Similarly, U.S. clinicians in 2011 prescribed 262.5 million courses of antibiotics (representing 842 prescriptions per 1000 persons), with family practitioners having prescribed the most antibiotic courses.5

Moreover, the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria is a global public health challenge that has accelerated as a result of the overuse and inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics worldwide.6-11 Numerous studies suggest that antibiotics are overly prescribed and ineffectively prescribed for viral infections rather than bacterial infections.11-13

These and other findings and observations demonstrate a need for more-precise interpretation of symptoms for antibiotic treatment and improved patient-oriented consulting skills to support the prescription of antibiotics.4,5

Patients’ perception of what they need for treatment predisposes them to expectations about the provider’s diagnosis, treatment plan, and prescriptions. Filipetto and colleagues14 found that 70% of 98 patients surveyed thought that viral infections require antibiotic treatment and that 86% to 92% thought that yellow nasal discharge or coughing up yellow mucus requires antibiotic therapy. These perceptions can influence patients’ expectations about treatment. Understanding these perceptions might improve patient and provider communication and decrease the inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics for ABRS.

Clinical Guidelines for ABRS

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery1 and the Infectious Disease Society of America15 have developed separate clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ABRS. These guidelines recommend that any of the 3 following clinical presentations be used to identify patients with ABRS: (1) symptoms lasting for 10 days or more and not improving; (2) symptoms that are severe, including fever of 39°C or higher, nasal discharge, and facial pain lasting 3 to 4 days; or (3) worsening symptoms with new fever, headache, or increased nasal discharge, typically after a viral upper respiratory infection lasting 5 or 6 days after initially seeming to improve. According to all guidelines, the ABRS diagnosis requires the presence of 1 or more of these 3 presentations.

ABRS Treatment

For the otherwise healthy patient, treatment of ABRS consists of symptomatic relief with decongestants, nasal washes, and if necessary, pain control with nonnarcotic analgesics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen.15

The most common organisms that cause bacterial ABRS are Streptococcus pneumoniae (38%), Haemophilus influenzae (35%), and Moraxella catarrhalis (16%).

The most appropriate antibiotics for initial therapy are amoxicillin-clavulanate (500 mg/125 mg orally 3 times a day, or 875 mg/125 mg orally twice a day) or doxycycline (100 mg orally twice a day, or 200 mg orally once a day) for 5 to 7 days.15 If antibiotic resistance is present, or if the treatment fails, the agents of choice are levofloxacin (500 mg orally once a day), moxifloxacin (400 mg orally once a day), or amoxicillin-clavulanate (2000 mg/125 mg orally twice a day) for 10 days.15 Macrolides (eg, clarithromycin, azithromycin) are not recommended for empiric therapy due to high rates of resistance among S pneumoniae (30%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is not recommended for empiric therapy due to high rates of resistance among both S pneumoniae and H influenzae (30% to 40%).15 The use of second-generation and third-generation oral cephalosporins is no longer recommended for empiric monotherapy of ABRS owing to variable rates of resistance among S pneumoniae. However, these agents are a good alternative for pregnant women.16

Provider and Patient Surveys

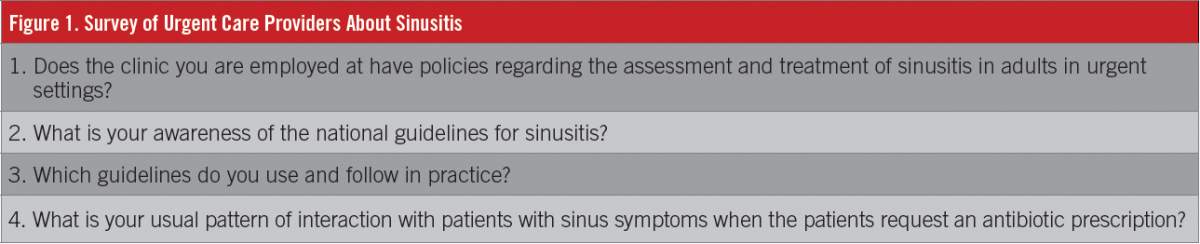

In 3 urgent care practices in 3 medium size cities in New York’s Hudson Valley, 11 health care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners [NPs], and physician assistants) were surveyed about their awareness of ABRS clinical guidelines and whether they thought patients presenting with sinusitis symptoms expected antibiotics (Figure 1). All providers were aware of the current clinical guidelines, and all answered that they believed that patients with these symptoms expected an antibiotic prescription. For patients presenting with ABRS symptoms, all providers stated that they would give an antibiotic prescription. Some of the reported reasons included a lack of time to explain why antibiotics are not needed, a provider perception that patients wanted an antibiotic, and a desire to please patients.

In the same setting, 115 adult patients presenting with sinusitis symptoms were given a survey about whether they thought antibiotics were needed for their symptoms (Figure 2). The sample comprised 42 men and 73 women, mostly white, between the ages of 31 and 40 years, and most with an undergraduate educational status. The most important finding was that 76% (n = 73) of patients surveyed indicated that they thought they needed an antibiotic for their symptoms that day (Figure 3).

Survey answers showed no significant difference across age, gender, ethnicity, and education level, with 2 exceptions. On the question, “Do antibiotics today not work as well as in the past?” women strongly agreed (mean, 5.12 [standard deviation (SD), 2.22]) compared with men (mean, 5.86 [SD, 2.57]), which was statistically significant (P = .055, 1-tailed test). On the question, “Do infections caused by viruses require an antibiotic?” women strongly disagreed (mean, 6.18 [SD, 2.72]) compared with men (mean, 4.95 [SD, 2.91]), and the difference was statistically significant (P = .013, 1-tailed test).

Patients also were asked about alternative treatment options for sinusitis symptoms. All told, 27% (n = 31) wanted decongestants, 15% (n = 17) wanted cough medication, 13% (n = 15) wanted antihistamines, 8% (n = 10) wanted pain relief, 3% (n = 4) wanted natural remedies, 1% (n = 2) wanted corticosteroids, and 0.08% (n = 1) wanted advice and eardrops.

Patients were asked about their symptoms and what their perceptions were if an antibiotic were needed. In total, 21% (n = 24) believed that coughing up yellow or green mucus that was running down the back of the throat required an antibiotic, 18% (n = 18) believed that having yellow or green mucus discharge from the nose required an antibiotic, 22% (n = 25) agreed that antibiotics do not work as well today as they did in the past, and 45% (n = 52) reported that they wait 4 to 6 days before they seek medical care when they have green or yellow mucus from their nose.

Patient Perceptions: The Literature

Filipetto and colleagues14 found that 70% of patients with symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection thought that viruses require antibiotic treatment, and that 90% of patients thought that yellow nasal discharge or coughing up yellow mucus required treatment with an antibiotic. This patient misconception may influence patient expectations about treatment, whether the illness is viral or bacterial. Akkerman and colleagues4 found that a shared perspective between patient and provider is positively associated with several factors, including resolution of problems and symptoms and patient satisfaction with the provider and the clinical encounter. Other factors included patient trust in and endorsement of the provider’s recommendations, adherence to treatment, and the patient’s assessment of self-management and self-efficacy. The providers’ perceptions of patients’ expectations play an important role when prescribing antibiotics that are not indicated according to published ABRS guidelines.

The results of one multicenter study17 of 3402 patients and 387 health care providers showed clear evidence that patient expectations and hopes for antibiotics, and especially clinician perceptions of these views, are independent predictors of antibiotic prescribing. Patients expecting antibiotics and hoping for them were prescribed antibiotics more frequently than those who were not, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.08 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.48, 2.93) for those expecting them and an OR of 2.48 (95% CI, 1.73, 3.55) for those hoping for them. There was no statistically significant association between patients asking for antibiotics and having been prescribed them (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.36, 1.04). Clinician perception that patients wanted an antibiotic significantly influenced antibiotic prescribing (OR, 12.18; 95% CI, 8.31, 17.84). Patient perception was not associated with illness severity; therefore, patient perception is a poor predictor for prescribing antibiotics. These findings showed that clinicians were not correctly assessing patient views on the use of antibiotics.17

Adverse Effects of Antibiotics

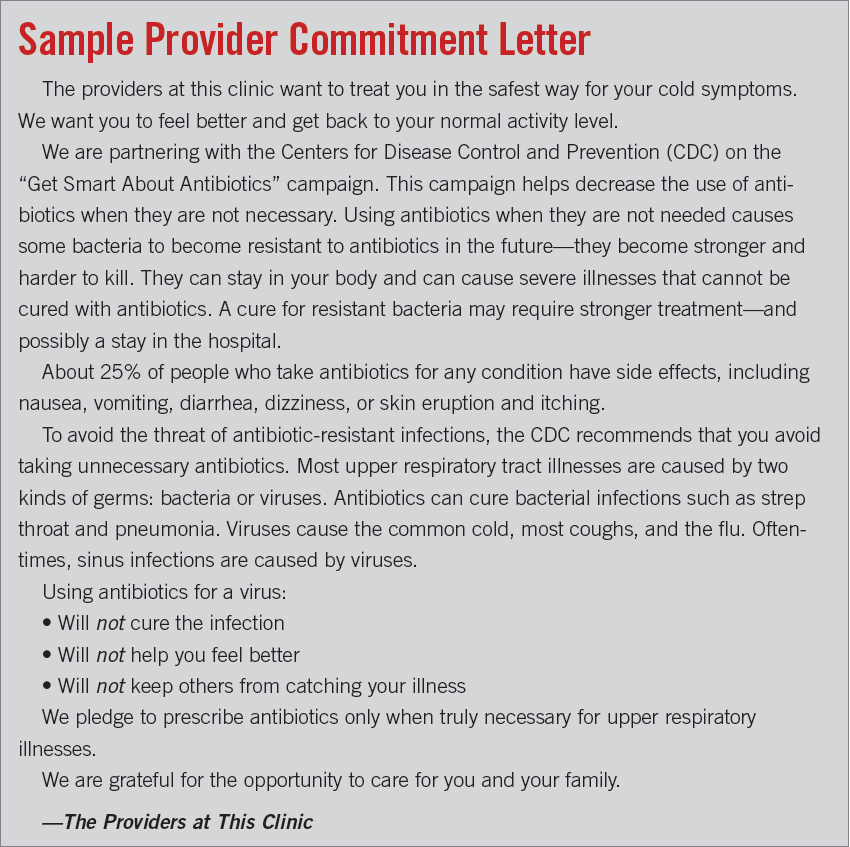

Approximately 1 in 4 people who take antibiotics for any condition experience adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, and skin eruption and itching. Severe reactions could lead to anaphylaxis, severe systemic reactions, acute laryngeal edema, severe bronchospasm, and death.6

Two meta-analyses enrolling a combined total of 6424 participants reported on the adverse effects of antibiotic treatment for acute sinusitis. Adverse effects, primarily diarrhea, were 80% more common in the antibiotic groups compared with the placebo groups and were reported among 30% to 74% of patients treated with antibiotics.18,19 Other commonly reported adverse effects included cutaneous eruption, vaginal discharge, headache, dizziness, and fatigue.

Resolution of ABRS Symptoms

Lemiengre and colleagues20 investigated 10 trials enrolling 2450 adult participants to assess the effect of antibiotics on clinically diagnosed rhinosinusitis in primary care settings. In the antibiotic treatment groups, 47% of participants were cured after 7 days and 71% after 14 days. Antibiotics can shorten the time to cure, but only 5 more participants per 100 will improve more quickly at any point between 7 and 14 days if they receive antibiotics instead of placebo. The authors concluded that there is no role for antibiotics in clinically diagnosed, uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

Smith and colleagues21 compared 4 meta-analyses enrolling a total of 9744 patients, published within the last 10 years and summarizing the results of randomized controlled trials comparing the effects of antibiotics with placebo for acute sinusitis. The included trials selected patients using inclusion criteria that increased the likelihood of bacterial sinusitis rather than viral sinusitis, such as more-severe signs and symptoms, longer duration of symptoms, and abnormal findings on radiographs or computed tomography scans. At 7 to 15 days after beginning treatment, cure or improvement was statistically significantly higher in the antibiotic groups compared with placebo groups, but the differences between the groups were small. Rates of cure or improvement in the placebo groups ranged from 64% to 80%, compared with 71% to 90% in the antibiotic groups. The difference in cure or improvement rates between the placebo and antibiotic groups ranged from 7% to 14% higher in the antibiotic groups. The rate of complications and recurrence did not differ between groups.

The authors of another meta-analysis22 found that older patients, those with more severe ABRS signs and symptoms, and those who reported a longer duration of symptoms took longer to cure but were no more likely to benefit from antibiotic treatment than were patients in other populations.

Results from a multimethod comparative case study12 including patients (children and adults) and clinicians in 18 family practices in a Midwestern state found that antibiotics were prescribed in 68% of outpatient visits (n = 298) for acute respiratory tract infections. According to current guidelines, 79% were determined to be unnecessary. A major finding revealed that patients pressured providers for antibiotic prescriptions during the clinic visit. The main reasons for prescribing antibiotics in this study included a direct request from the patient, a diagnosis suggested by the patient, a set of symptoms specifically indexing a particular diagnosis, portraying severity of illness, appealing to life-world circumstances, and previous use of antibiotics by the patient for similar symptoms. Providers rationalized their antibiotic prescriptions by reporting medically acceptable reasons such as the presence of yellow mucus in patients.12

Prescribing Across Provider Types

Ladd completed a cross-sectional retrospective review of data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 1997 to 2001.13 Data were collected on a national probability sample of 506 NPs and 13,692 medical doctors (MDs). The visits were with patients with nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection, viral pharyngitis, and bronchitis.

Bivariate analysis found no significant differences in antibiotic prescribing for viral upper respiratory tract infections by NPs (50.4%) and MDs (53%). Broad-spectrum antibiotics accounted for 36.6% of the NP antibiotic prescriptions and for 33.2% of the MD antibiotic prescriptions. Multivariate analysis identified several clinical and nonclinical factors that are associated with NP antibiotic prescribing. The author concludes that the excessive use of antibiotics for upper respiratory infections of viral etiology by both NPs and MDs suggests the continuing need for the use of education tools to educate patients, as well as increasing involvement by both groups of providers in the dissemination of clinical guidelines and system-based quality assurance programs.

Summary

In summary, despite the evidence that providers are aware of guidelines for ABRS and want to treat patients that present with symptoms of ABRS so they will improve and not prescribe unnecessary antibiotics, providers may overestimate patient expectations for antibiotic prescriptions. Asking a single question, “What kind of treatment are you wanting today?” could increase provider and patient understanding, and give providers options other than antibiotics for ABRS symptoms.

Meagan Soltwisch, DNP, FNP-C, practices urgent care medicine as a family nurse practitioner at Pulse-MD Urgent Care’s locations in New York’s Mid-Hudson Valley.

Nancy Beckham, PhD, FNP-C, is an associate professor at Gonzaga University’s School of Nursing and Human Physiology and practices primary care medicine at the Mann-Grandstaff Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Spokane, Washington.

References:

- Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1-S31.

- Fagnan LJ. Acute sinusitis: a cost-effective approach to diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(8):1795-1802.

- Smith SS, Evans CT, Tan BK, Chandra RK, Smith SB, Kern RC. National burden of antibiotic use for adult rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5): 1230-1232.

- Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, Verheig TJM. Determinants of antibiotic overprescribing in respiratory tract infections in general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(5):930-936.

- Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1308-1316.

- Renaudin J-M, Beaudouin E, Ponvert C, Demoly P, Moneret-Vautrin D-A. Severe drug-induced anaphylaxis: analysis of 333 cases recorded by the Allergy Vigilance Network from 2002 to 2010. Allergy. 2013; 68(7):929-937.

- Albrich WC, Monnet DL, Harbarth S. Antibiotic selection pressure and resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(3):514-517.

- Bronzwaer SLAM, Cars O, Buchholz U, et al; European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. The relationship between antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002; 8(3):278-282.

- Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M; ESAC Project Group. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579-587.

- Hay AD, Thomas M, Montgomery A, et al. The relationship between primary care antibiotic prescribing and bacterial resistance in adults in the community: a controlled observational study using individual patient data. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(1):146-153.

- Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229-241.

- Scott JG, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, Orzano AJ, Jaen CR, Crabtree BF. Antibiotic use in acute respiratory infections and the ways patients pressure physicians for a prescription. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):853-858.

- Ladd E. The use of antibiotics for viral upper respiratory tract infections: an analysis of nurse practitioner and physician prescribing practices in ambulatory care, 1997–2001. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005; 17(10):416-424.

- Filipetto FA, Modi DS, Weiss LB, Ciervo CA. Patient knowledge and perception of upper respiratory infections, antibiotic indications and resistance. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2008;2:35-39.

- Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al; Infectious Disease Society of America. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1651-1672.

- Czeizel AE, Rockenbauer M, Sørensen HT, Olsen J. Use of cephalosporins during pregnancy and in the presence of congenital abnormalities: a population-based, case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(6):1289-1296.

- Coenen S, Francis N, Kelly M, et al; GRACE Project Group. Are patient views about antibiotics related to clinician perceptions, management and outcome? A multi-country study in outpatients with acute cough. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76691.

- Rosenfeld RM, Singer M, Jones S. Systematic review of antimicrobial therapy in patients with acute rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl): S32-S45.

- Falagas ME, Giannopoulou KP, Vardakas KZ, Dimopoulos G, Karageorgopoulos DE. Comparison of antibiotics with placebo for treatment of acute sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(9):543-552.

- Lemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, Young J, De Sutter AIM. Antibiotics for clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD006089. doi:10.1002/ 14651858.CD006089.pub4.

- Smith SR, Montgomery LG, Williams JW Jr. Treatment of mild to moderate sinusitis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(6):510-513.

- Young J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2008;371(9616):908-914.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute pharyngitis in adults: physician information sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-acute-pharyngitis.html. Updated April 17, 2015. Accessed February 4, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get Smart About Antibiotics Week. http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/week/. Updated October 30, 2015. Accessed February 4, 2016.

- Meeker D, Knight TK, Friedberg MW, et al. Nudging guideline-concordant antibiotic prescribing: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174(3):425-431.

- Linder JA, Singer DE. Desire for antibiotics and antibiotic prescribing for adults with upper respiratory tract infections. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):795-801.