Prescribing Error in a Geriatric Outpatient Due to Patient Misidentification

Case Presentation

AG, a 75-year-old Hispanic female, was informed by the receptionist in the waiting room of her primary care clinic that the physician with whom she had an appointment was available to see her. She had been attending this multispecialty teaching clinic regularly and was accustomed to seeing new resident physicians from different specialties. AG was sent to the office of the psychiatry resident who had recently started the clinic rotation and was scheduled to see a patient “AG” that afternoon. The resident had reviewed AG’s chart prior to asking the receptionist to call her, and was prepared to meet with an elderly woman who had been experiencing improvement in a depressive episode in association with antidepressant treatment. AG entered the resident’s office accompanied by her home health aide and a translator, whom the clinic provided because of AG’s limited fluency in English.

The resident introduced herself and explained that she was AG’s new psychiatric resident. The resident inquired about symptoms of depression, and the patient reported that she did not feel depressed and added that she had only come to the clinic for this scheduled follow-up to receive a refill for her “blood pressure medications.” Through the translator, the resident confirmed that AG did not have any side effects related to the antidepressant listed in the chart. Assessment of AG’s cognitive status revealed that she could not recall the precise date and could not name all of the medications that she was taking, but that she was oriented to place and person, and appeared to have relatively intact cognition aside from a mild recent memory deficit.

The resident inquired further about AG’s medications, and then asked to see her medication bottles. AG produced the two nearly empty bottles of her antihypertensive medications and said that she had left the bottles of the other medications she was taking at home. The bottles of antihypertensive medications corresponded to those listed in her chart. AG was asked about the antidepressant that was also noted in the chart, but both AG and her aide stated that they could not recall the names or purposes of her other medications. The psychiatrist then wrote a new prescription for the antidepressant, entered a note in her chart, and scheduled a follow-up appointment. She noted that AG had an appointment later that day to see the clinic internist who was prescribing the medications for hypertension.

The next day, a different patient with the same name of “AG” arrived at the clinic and asked to see the psychiatrist. She told the receptionist that she had had an appointment at the clinic the previous day, but she had arrived late and then left after she became tired of waiting because her name had not been called. She had now returned to obtain a refill of her antidepressant. The second AG was approximately the same age and was taking the same antihypertensive medications as the AG who had seen the psychiatry resident on the previous day. After reviewing the previous day’s list of clinic appointments with the receptionist, the psychiatry resident realized that the AG seen the previous day had had an appointment with her internist on that day and not with the psychiatry resident.

Discussion

The prescription or administration of an incorrect medication is a common form of medication error1 that is associated with a high risk of serious untoward health consequences. Among inpatients, medication error rates as high as 1.5-5.3 per 100 orders have been reported.2,3 Initiatives to assure medication reconciliation have been effective in reducing the frequency of medication errors among hospitalized patients.4,5 Although errors in ambulatory settings are particularly difficult to detect, medication errors in outpatients are more common than in inpatients and are also associated with serious adverse consequences.6,7

The risk for medication errors increases at points of transition between different levels of healthcare.8,9 In contrast to the vertical changes that occur at hospital admissions and discharges, times of resident rotation in teaching clinics are “horizontal transition” points that can lead to prescribing errors unless newly assigned physicians rapidly become knowledgeable about their new patients’ clinical histories and medication regimens. Times of rotation at multispecialty teaching clinics that treat geriatric patients are at particular risk for medication errors because geriatric patients commonly take a large number of medications10 and are frequently treated by multiple physicians from different specialties. Decreased cognitive functioning may further compromise the ability of geriatric patients to remember the names and purposes of the medications that they are taking. Finally, language barriers may add to aging-related factors in causing prescribing errors among older patients seen in multilingual clinics.11 We report an illustrative case in which a combination of these risk factors contributed to patient misidentification, resulting in one patient being prescribed a medication intended for a different clinic patient with the same name.

Patient misidentification was an obvious cause of this medication error. Studies of the frequency of patient misidentification and procedures to minimize the risk have generally focused on inpatients because of the serious consequences of errors in hospital settings. Interventions such as “time-out” procedures, which require re-checking to assure that a specific intervention has been ordered for a particular patient before proceeding, are particularly useful before initiating invasive or high-risk procedures such as transfusions; however, the practicality of systematically applying these safeguards before prescribing to outpatients is uncertain. Although initiatives to reduce misidentification errors by improving the registration process have shown promise in inpatient settings, the approach appears to be less effective in outpatients.12 Moreover, improving the registration process does not address the critical role that doctor-patient communication plays in assuring that medications are prescribed and taken appropriately. The inadequate communication in the case reported is illustrated by the resident’s not resolving the discrepancy between AG’s perception that she had come for a refill of her antihypertensive medication, and the resident’s perception that the patient was receiving continued antidepressant treatment for a major depression.

Results from large-scale patient surveys13 and direct observational studies14 document that physicians commonly fail to discuss the names of newly prescribed medications with their patients or specify how the medications should be taken. The Institute of Medicine’s goal of increasing healthcare literacy argues that doctor-patient communications should extend beyond focused assessments of treatment responses and side effects.15 The application of computerized record systems and checklists to assure that outpatient medication reconciliation occurs can reduce prescribing errors, but does not address the larger goal of increasing patients’ participation in their care.

AG’s case highlights factors that should alert clinicians to the particular need to assure that the information communicated to patients has been understood. AG’s cognitive deficits and needs for a home health aide and a translator indicated potential barriers to AG’s full participation in her treatment. Assuring that she was the “correct” AG was only the first step in a process that should enhance AG’s collaboration in her treatment. Evidence for limited patient understanding of the need for relapse prevention and for nonadherence to antidepressant maintenance among older patients in primary care settings16 underscores the need for greater attention to patient education at times of antidepressant renewals. Thus, patient education and collaboration is particularly relevant to the maintenance treatment of chronic conditions such as depression, diabetes, and hypertension because the absence of current symptoms does not bear on the need for continued pharmacotherapy.

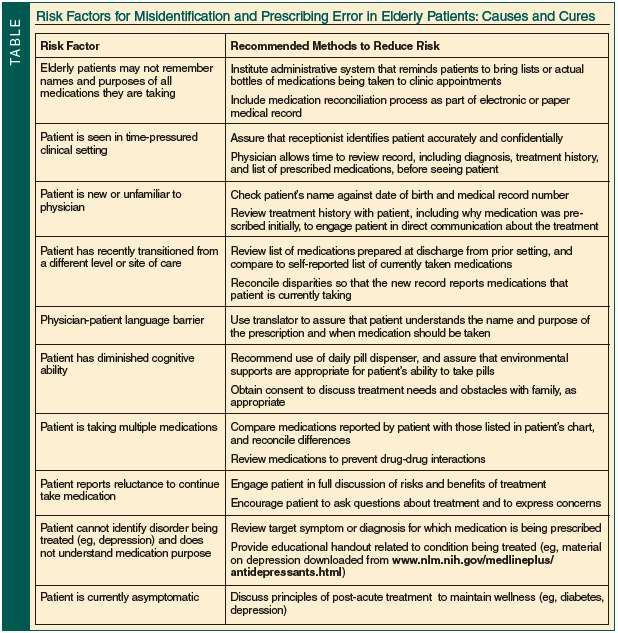

This unusual case illustrates factors beyond the coincidence of identical names that may contribute to misidentification prescribing errors. These include residents serving as psychiatric consultants in primary care clinics, lack of familiarity between patients and their physicians at times of residents’ rotations in teaching clinics, physician-patient language barriers, and factors specific to consulting on geriatric patients. The incident demonstrates one unusual, untoward consequence of a physician inquiring about current symptoms and potential side effects without assuring that the patient fully understands the treatment prescribed. The Table, which was developed as a result of the incident with AG, presents a list of common factors that increase the risks for misidentification and prescribing errors and methods to reduce these events. Recommended approaches range from such concrete techniques as double-checking the identities of unfamiliar patients to methods designed to improve communication and engage patients’ participation in their treatments. Educational handouts such as materials from the National Institute of Mental Health (which can be downloaded at www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/antidepressants.html) both provide patients with additional information about the diagnosis and treatment and continue the doctor-patient communication beyond the time of the appointment. The significance of assuring that physician-patient communication is adequate is particularly relevant to the long-term management of patients with chronic conditions such as depression that require continued adherence to treatment at times when patients are asymptomatic.

Outcome of the Case Patient

Fortuitously, the misidentification error was recognized when the second AG arrived at the clinic. The error was corrected by asking the “first” AG to return to the clinic, retrieving the antidepressant medication, and having her antihypertensive medications refilled after her blood pressure had been checked. The same psychiatry resident reviewed the names of AG’s medications and the reasons for taking them with the patient and her home health aide. AG and the aide were advised to keep a list of AG’s current medications and to bring the list to future appointments with physicians. The second AG had her antidepressant medications refilled after the medications that she was taking had been reviewed with her. Neither patient had taken a dose of an incorrect medication or had suffered harm as a result of the misidentification. The clinic medical director was informed about the situation, and meetings were scheduled to inform the clinic staff and house offices of the incident and to discuss initiatives to reduce the risk of patient misidentification in the future.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Mendoza is from Columbia University Medical School, New York State Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry, New York, NY; and Dr. Meyers is Professor of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York-Presbyterian Hospital – Westchester, White Plains, NY. Dr. Lantz is Chief of Geriatric Psychiatry, Beth Israel Medical Center, First Ave @ 16th Street #6K40, New York, NY 10003; (212) 420-2457; fax: (212) 844-7659; e-mail: mlantz@chpnet.org.