Pott Puffy Tumor: A Rare Case Presenting in a 5-Year-Old Child

A 5-year-old boy with a past medical history of asthma and food allergies was referred to our pediatric hospital by his local hospital emergency department (ED) for further management of Pott puffy tumor and intracranial extension of sinusitis with epidural abscess. The boy had initially presented after falling off his bunk bed and hitting his forehead on the steps of the bed. He did not complain of significant pain after the fall, but forehead swelling developed the following day. He was taken to a local hospital, where a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed forehead swelling and sinus disease, but no fracture or bony destruction. A few days later, the boy returned to the hospital with fever and cough and was diagnosed as having pneumonia and sinusitis, prompting his physician to treat him with a course of amoxicillin. Over the next 2 days, he clinically improved, with reduction of the forehead swelling.

However, a few days later, his forehead swelling worsened, and he developed left periorbital soft tissue swelling. He also was febrile and had an unremitting headache. The boy’s pediatrician immediately referred him to the local ED, where he underwent evaluation. The patient’s complete blood count was significant for leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 17,600/µL (reference range, 5000-14,500/µL) with 71% neutrophils (reference range, 40%-80%), and his repeat CT scan was significant for interval development of forehead abscess with associated erosive bone changes and epidural abscess with mass effect. The boy was given a dose of piperacillin/tazobactam and transferred to our tertiary care center.

On initial physical examination at the pediatric tertiary care center, the patient was afebrile. Significant forehead swelling without overlying skin changes was observed. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated, and the results of otoscopic and neurologic examinations were unremarkable. Left periorbital swelling was observed, but extraocular movements were grossly intact.

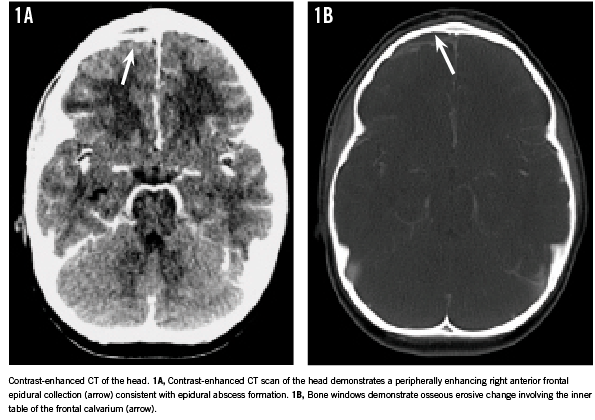

The contrast-enhanced CT of the patient’s head (Figures 1A and 1B) performed at the outside ED revealed opacification of the frontal paranasal sinus with expansion and erosion of the frontal calvarium with intracranial extension evidenced by a peripherally enhancing frontal epidural collection. Extensive soft tissue infiltration was noted in the overlying anterior scalp, with swelling of the left periorbital soft tissues without orbital cellulitis. Paranasal sinus mucosal disease also involved the bilateral maxillary, right sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses.

Laboratory data obtained at our institution confirmed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 17,000/µL (reference range, 5000-14,500/µL), and the patient was mildly anemic with hemoglobin of 10.6 g/dL (reference range, 11.5-15.5 g/dL). Blood culture was obtained but remained sterile. C-reactive protein level was elevated at 156 mg/L (reference range, < 9 mg/L), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased to 62 mm/h (reference range, < 10 mm/h).

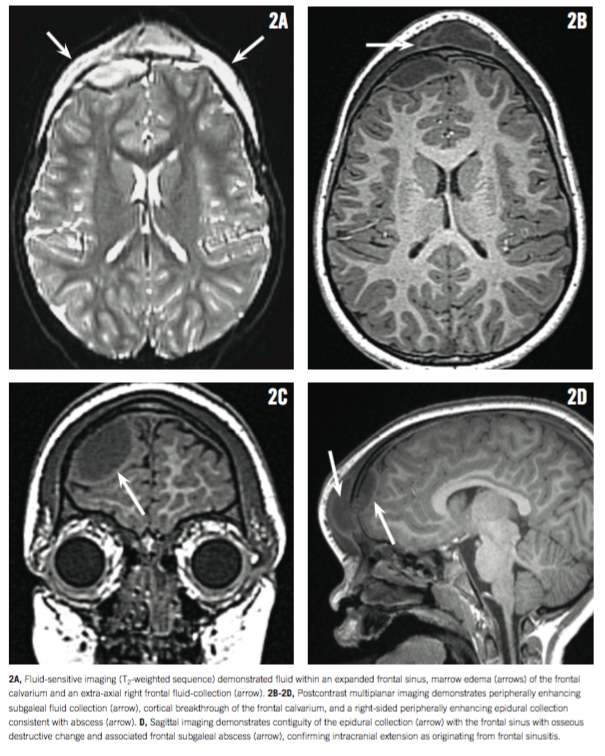

Otolaryngology and neurosurgery were consulted, and an otolaryngologist unsuccessfully attempted to aspirate fluid from the boy’s swollen forehead. Neurosurgery requested magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the child’s head (Figures 2A and 2B), and the results of the MRI revealed frontal paranasal sinus disease with marrow edema involving the frontal calvarium, consistent with frontal bone osteomyelitis. Intracranial extension was demonstrated, with a predominantly right-sided anteriofrontal peripherally enhancing epidural collection, consistent with frontal epidural abscess. A large subgaleal abscess was also identified in the midline frontal scalp. Left periorbital soft tissue edema without orbital cellulitis was observed.

The patient was admitted to our pediatric intensive care unit and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic coverage was initiated, including vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, and metronidazole. A few hours later, a neurosurgeon performed drainage of the subgaleal abscess and craniotomy in the right frontal bone for drainage of the epidural abscess. Subgaleal fluid and epidural pus were sent for anaerobic and aerobic cultures, which later grew Streptococcus intermedius.

The boy was discharged from our hospital 9 days after surgery and was treated by our infectious disease division using intravenous penicillin treatment with continued outpatient management. His clinical condition and inflammatory markers continued to normalize without evidence of epidural abscess recurrence. While this child presented to our institution with a tentative diagnosis of Pott puffy tumor on the basis of contrast-enhanced CT imaging obtained at an outside ED, MRI further confirmed the presence of frontal bone osteomyelitis and characterized the previously identified epidural abscess, prompting successful neurosurgical intervention.

DISCUSSION

Pott puffy tumor is a relatively rare clinical entity in the modern era that has become more frequently reported in the medical literature.1-3 It is defined as an abscess of involving the periosteum with associated osteomyelitis of the frontal bone that manifests as focal swelling of the forehead.4 Antibiotic usage for uncomplicated sinusitis paired with earlier presentation of patients for clinical management has reduced the incidence of this process. In addition, improvement in and increased access to diagnostic imaging, as well as physicians’ increased awareness of the condition, has also led to a decrease in intracranial complications of sinusitis.1 Without early identification leading to appropriate antibiotic therapy and surgical management when necessary, serious complications, including meningitis, intracranial abscess, cerebritis, and venous sinus thrombosis can occur.5

Pediatric generalists should have a high index of suspicion for Pott puffy tumor in patients who present with recent trauma or sinus disease and progressive forehead swelling. A meta-analysis of published cases from 1950-2010 revealed that the mean age of patients with Pott puffy tumor, with orbital involvement, was approximately 17 +/- 12 years.1 This broad age distribution is related to the wide range of normal development and pneumatization of the frontal sinus, which occurs at 7 years of age on average, but development often continues until complete pneumatization occurs in late adolescence.6

Our patient experienced significant forehead trauma prior to presentation; in the pediatric age group, trauma is a predisposing factor in 14% of Pott puffy tumor cases.7 Different mechanisms of head injury as a predisposing factor to this illness have been postulated.8 When our patient was diagnosed as having pneumonia and sinusitis upon his return to the ED at an adult hospital, amoxicillin was initiated. Failure to have very close outpatient follow-up to determine treatment success may have contributed to the spread of his infection.9 Jafri and colleagues reported a case similar to ours, in which an 11-year-old girl was treated for sinusitis with amoxicillin with signs of clinical improvement but went on to develop Pott puffy tumor with S intermedius as the identified pathogen.10

CONCLUSION

It is important to rely on clinical examination skills for suspicion and diagnosis because cases of Pott puffy tumor can occur even in the setting of negative cultures from various specimen sources.11 Obtaining MRI of our patient’s head was helpful to confirm the extent of intracranial disease and demonstrate any intracranial or orbital involvement that could be less conspicuous on CT (eg, meningeal involvement).12 MRI, including postcontrast sequences, should be considered in all cases of suspected Pott puffy tumor. MRI affords improved detection of intracranial infections in general with greater sensitivity for complications encountered in Pott puffy tumor, including intracranial abscess formation, meningitis, and osteomyelitis.13 Moreover, in the pediatric population, MRI is preferred in avoiding exposure to ionizing radiation encountered with CT. While CT remains more accessible and easier to perform in the community, short-duration MRI protocols and pediatric sedation available at tertiary care centers can increase access to MRI for children with suspected intracranial infections.

Patients with recent head trauma who develop signs and/or symptoms suggestive of sinusitis should be treated aggressively and closely followed. This case illustrates that even in children who may be too young to have developed frontal sinuses, infection of the frontal sinus with extension is possible and should be considered, especially in cases with soft forehead swelling. Adult emergency medicine providers should promptly refer patients like this to pediatricians for management. Recognition of new symptoms such as fever, headache, and changes in serial neurologic and physical examination results in patients with risk factors in the setting of sinusitis can serve to potentially initiate earlier and more aggressive management to prevent the development of intracranial extension as seen in Pott puffy tumor.

Waleed H. Kurtom, MD, is with the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Neonatology, at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida.

Andrew J. Degnan, MD, is with the Department of Radiology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and with Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, both in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Randall G. Fisher, MD, is with the Department of Pediatrics at Eastern Virginia Medical School and with Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters, both in Norfolk, Virginia.

References

1. Nisa L, Landis BN, Giger R. Orbital involvement in Pott’s puffy tumor: a systematic review of published cases. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(2):e63-e70.

2. Parida PK, Surianarayanan G, Ganeshan S, Saxena SK. Pott’s puffy tumor in pediatric age group: a retrospective study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(9):1274-1277.

3. Blumfield E, Misra M. Pott’s puffy tumor, intracranial, and orbital complications as the initial presentation of sinusitis in healthy adolescents, a case series. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18(3):203-210.

4. Kombogiorgas D, Solanki GA. The Pott puffy tumor revisited: neurosurgical implications of this unforgotten entity. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(2 suppl):143-149.

5. Salomão JF, Cervante TP, Bellas AR, et al. Neurosurgical implications of Pott’s puffy tumor in children and adolescents. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30(9):1527-1534.

6. Cherry JD, Mundi J, Shapiro NL. Rhinosinusitis. In: Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, Steinbach WJ, Hotez P, eds. Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:193.

7. Skomro R, McClean KL. Frontal osteomyelitis (Pott’s puffy tumour) associated with Pasteurella multocida: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Infect Dis.1998;9(2):115-121.

8. Tudor RB, Carson JP, Pulliam MW, Hill A. Pott’s puffy tumor, frontal sinusitis, frontal bone osteomyelitis, and epidural abscess secondary to a wrestling injury. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9(6):390-391.

9. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):e72-e112.

10. Jafri L, Farooq O. Pott’s puffy tumor. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(2):250-251.

11. Urík M, Machač J, Šlapák I, Hošnová D. Pott’s puffy tumor: a rare complication of acute otitis media in child: a case report. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(9):1589-1591.

12. Hoxworth JM, Glastonbury CM. Orbital and intracranial complications of acute sinusitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Amer. 2010;20(4):511-526.

13. Nickerson JP, Richner B, Santy K, et al. Neuroimaging of pediatric intracranial infection—part 1: techniques and bacterial infections.

J Neuroimaging. 2012;22(2):e42-e51.