Peer Reviewed

Pitfalls of Interstitial Lung Disease

Authors:

Chinh T. Phan, DO, and Samuel Louie, MD

Citation:

Phan CT, Louie S. Pitfalls of interstitial lung disease. Consultant. 2015;54(2):120-124.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) has a history of baffling clinicians for several reasons—2 of those being confusing terminology and classification, which continue to thwart clinicians’ ability to establish a clear diagnosis. Additionally, despite promising advances in drug treatment to delay progression to fibrosis, many patients are being treated with older methods that are ineffective in improving survival, particularly for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Continued use of the term ILD can be blamed on the inflammatory changes that occur in the lung interstitium sandwiched between the alveolar epithelium and the capillary endothelium. Alveolar capillaries and peripheral small airways (traction bronchiectasis) can be involved in the disease process. Histopathological changes of “fibrosing alveolitis” cause physiological changes that can be detected by pulmonary function testing (uniformly smaller than expected lung volumes resulting in restrictive lung disease and a low carbon monoxide diffusing capacity or DLco), chest x-ray imaging, and high-resolution CT scan (HRCT) of the chest that display thickening of the lung interstitium.

It helps to remember that ILD is not actually a disease, but rather a classification of chronic pneumonias and disorders that primarily inflame and fibrose the alveolar walls. These conditions have no relationship to each other except that they can cause death from progressive pulmonary fibrosis and respiratory failure. The incentive for diagnostic evaluation always begins in the clinic office: To correctly diagnose the specific ILD present, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion, recognize risk factors, maintain contact with patients, and closely monitor changes in clinical histories over time.

DIAGNOSIS

The chief complaints of chronic exertional dyspnea and/or dry cough should not be ascribed to old age. Refrain from ordering tests until a complete and detailed history is taken first. A focused clinical history, which usually provides the greatest amount of information in the briefest amount of time, can help narrow the differential diagnosis and exclude asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cardiomyopathy. Asking about symptoms, their onset, and factors that relieve or agravate them is essential.

Physical examination of the lungs typically reveals few clues in the diagnosis of ILD. Dry crackles are best auscultated at the lungs bases just above the diaphragm posteriorly and suggest pulmonary fibrosis. On the other hand, the remainder of the examination may hint at a systemic disease linked to or associated with ILD. For example, xerostomia in Sjörgen’s syndrome, lupus pernio and erythema nodosum for sarcoidosis, malar rash in systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid nodules in rheumatoid arthritis, clubbing in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and lymphangitic carcinomatosis or mononeuritis multiplex in Churg-Strauss syndrome (also known as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis or allergic granulomatosis), and abdominal pain with bloody diarrhea from inflammatory bowel disease.

Thorough documentation of occupational history, hobbies, underlying medication conditions, and drug use is also imperative in assessing the presence of ILD. HRCT chest scans and lung biopsies may also be necessary to further clarify symptoms, especially as overlapping symptoms makes early diagnoses of ILD so difficult. For example, exertional dyspnea in ILD resembles dyspnea experienced by patients with more common ailments such as asthma, COPD, and heart disease. Though ILD can be short-lived in some cases, the tendency is for it to manifest as chronic and progressive. Prognosis varies considerably depending on whether the ILD in an individual patient has a known or unknown cause or association.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION FROM PATIENT HISTORY

The classic clinical profile of an ILD patient reflects clinicians’ limited ability to suspect and diagnose ILD early. Clinicians must rely on patients and on themselves to be alert to complaints of dyspnea and/or persistent dry cough. Broad association between dyspnea and other symptoms, however, makes delayed diagnosis of ILD all too common. For example, in adult smokers between the age 40 and 70 years, initial diagnosis may be COPD based on the symptoms of cough and dyspnea on exertion. Dyspnea, though, is a very nonspecific symptom; two-thirds of cases are due to asthma, COPD, cardiomyopathy and ILD—a primary “pitfall” of ILD detection.

Patients’ nonspecific signs and symptoms must be serious enough to interfere with daily activities of living and elicit concern, but they, or their family, typically ascribe dyspnea to aging, deconditioning, and even depression. Patients must volunteer a chief complaint or the clinician must be curious enough to begin asking probing questions. A complete history often reveals a known cause for ILD or a systemic disorder associated with ILD before HRCT is done. The acronym “SOURCE”1 is a helpful tool that should be used for an efficient evaluation of ILD. (Table 1)

Symptoms, Occupations, and More >>

SYMPTOMS

Not all ILD patients are elderly (ie, 65 years or older), as it really depends on the underlying condition. But be ready for aging to be a chief complaint. For example, sarcoidosis is an ILD that typically affects young adults (range 20 to 50 years of age), whereas IPF attacks elderly patients without an identifiable known cause of ILD, primarily men in the sixth and seventh decade of life. Look for progressive exertional dyspnea, particularly with exercise, persistent, nonproductive or dry cough, and extrapulmonary symptoms related to a different underlying disease.

Productive cough and hemoptysis are not typical symptoms of ILD, but can be a part of an exacerbation of ILD or a complication, for example, pulmonary embolism, lung cancer, bacterial pneumonia, or heart failure. However, both fever and weight loss can present intermittently in ILD.

Best practice is to determine the chronologic course of the patient’s complaint. Older, less active patients may have difficulty recalling the onset of dyspnea. They may remember more readily if you question them about small changes in their performance of everyday tasks, such as walking the dog, showering, getting the mail or taking out the garbage, going to church, or anything that involves walking.

OCCUPATIONS

OCCUPATIONS

A lifetime occupational history is invaluable in the diagnosis of many pulmonary diseases, especially ILD. Automotive repair workers, pipe fitters, electricians, and patients with military service may have been exposed significantly to asbestos. Heavy metal workers and those involved with flux may be at risk for ILD. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) to organic chemicals or matter, animals, grains, and wood dust may be mistaken for asthma and clues can emerge from the occupational history if the patient is a farm worker or bird breeder. Remember, patients with occupational related HP may report a lessening of symptoms during weekends and holidays then subsequent aggravation upon returning to work.

Figure 1. (Right) Flow-volume loop consistent with restrictive lung disease. Note the inspiratory and expiratory high flow

(L/sec) and the narrow shape of both the inspiratory limb and expiratory limb of the flow-volume loop giving the appearance of a doorstop. Remember, the flow volume loop may appear “normal” in the very early stages of ILD before lung volumes fall below 80% of predicted.

UNDERLYING MEDICAL CONDITIONS AND DRUGS

Seek a history of connective tissue disease (CTD) and malignancies such as breast cancer or melanoma. Besides occupational and environmental agents, medicinal agents such as Chinese herbs, can lead to the development of ILD. Drugs such as nitrofurantoin for chronic prophylaxis of urinary tract infections can cause acute pneumonitis as well as chronic and progressive ILD with pulmonary fibrosis years after administration. Amiodarone is notorious for causing ILD as is methotrexate for RA. Whether there is a direct link between a drug or agent and inflammatory lung injury leading to ILD is unclear, unlike bleomycin lung toxicity when patients are exposed to oxygen. Most often the toxic reaction to the drug is labeled idiosyncratic.

RELIEVING AND AGGRAVATING FACTORS

Factors that relieve or aggravate symptoms are important to document. Paying attention to worsening of symptoms at the job site or at home is particularly helpful when evaluating possible HP.

CONTACTS

Personal contacts, use of illicit drugs, and use of nutritional supplements can potentially provide clues to why a patient may have ILD. The resurgence of talc-diluted heroin will increase the occurrence of talc granulomatosis of the lung and smoking crack cocaine can cause bronchiolitis obliterans. Exposure to people with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and respiratory viruses, (eg, influenza or respiratory syncytial virus) tend to cause acute interstitial pneumonias and may persist in some cases.

EXTRAPULMONARY SYMPTOMS

Do not overlook dry eyes and mouth (Sjögren’s syndrome), dysphagia (systemic sclerosis), or sinusitis with epistaxis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis). Palpitations, syncope, dysesthesias, erythema nodosum, and sore shins may be manifestations of sarcoidosis.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Crackles on auscultation of the chest are very often a late finding indicative of pulmonary fibrosis but does not conclude the examination. Look for evidence of uveitis, skin and joint findings typical of CTDs, and chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Order a 6-minute walk to measure exercise tolerance and detect hypoxemia on exertion, another sign of more severe ILD.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

A normal chest x-ray does not rule out ILD. Gather all the old past images to review. Pulmonary function testing (PFT), including spirometry, lung volumes, and DLco should be done on every patient suspected of ILD to evaluate the degree of pulmonary impairment. A restrictive pattern (forced vital capacity [FVC]) and total lung capacity less than 80% predicted in early ILD, or a mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern, may accompany restriction in sarcoidosis, eosinophilic granuloma, HP, or lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). A low DLco (less than 80% predicted) may suggest ILD and concomitant pulmonary vascular disease such as pulmonary vasculitides.

HRCT of the chest is highly sensitive in detecting patterns and distributions consistent with ILD though not very specific. HRCT should be ordered in patients only after clinical history, PFTs, and chest x-ray provide insufficient evidence of a specific ILD.4 It is not necessary for all cases of ILD to have HRCT, for example, in pulmonary sarcoidosis where diagnosis can be confirmed without HRCT. Evidence from HRCT may help narrow the differential diagnosis and allow the clinician to contemplate the need for fiberoptic bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsies or surgical lung biopsy typically by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. It is appropriate to remember Murin’s Rule here: “The higher your level of suspicion of a disease or the worse the potential consequences of missing the diagnosis, the higher the level of evidence you should require in order to exclude that disease from your differential.”

To biopsy or not to biopsy is the question that should not be asked until a thorough evaluation without lung biopsy is completed, including consultation with a pulmonologist. Tissue diagnosis may be necessary to begin treatment specific for a particular ILD, such as fibroblastic foci in IPF. Classic HRCT findings of honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and peripheral bibasilar reticular abnormalities without ground glass opacities is typically enough to make the clinical diagnosis of IPF without surgical lung biopsy.

Figure 2. Chest x-ray view showing diffuse interstitial markings consistent with chronic interstitial lung disease.

Classification of ILD

The evaluation of ILD should be approached with a practical framework to cover the pertinent features of each category. ILD can be due to 1 of 5 categories of etiologies (known causes, unknown or idiopathic, CTDs, granulomatous diseases, and miscellaneous). The acronym “DOE"2 helps clinicians remember the importance of querying exposures such as drugs, occupational, and environmental. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), which are rare, are based on histological and radiographical criteria. It is important to differentiate usual or interstitial pneumonia (UIP) from other IIPs because UIP has a poorer prognosis than other IIPs. (Table 2).

These 7 pathohistological patterns (remember the mnemonic “NU COP, DARL?) can also be found in other diseases such as CTDs, which is another ILD classification, but is idiopathic when the cause is unknown despite a comprehensive workup. Infectious and noninfectious granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis, GPA, HP, and mycobacterial or fungal infections can also affect the lung interstitium. Lastly, very rare diseases such as LAM, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis fall outside of the aforementioned categories and therefore can be classified into a miscellaneous group. Along with SOURCE, having a simple, yet concise classification system can lead to the correct diagnosis of ILD.

TREATMENT

Refrain from empiric drug treatment(s) until the cause of exertional dyspnea and dry cough is sufficiently clear and other more common causes of exertional dyspnea are eliminated, such as COPD and heart failure. Asthma, COPD, ILD, and cardiomyopathy account for two-thirds of chronic dyspnea cases. The entire evaluation of dyspnea should take less than 3 weeks to complete even for ILD.

The goals of treatment and management of ILD should be identical to asthma and COPD: reduce symptoms and reduce risks, particularly from acute exacerbations and associated complications, including acute pulmonary embolism, acute pneumonia, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and lung cancer, all of which shorten survival. Smoking cessation is imperative, particularly in IIPs such as desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis- associated interstitial lung disease.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is of benefit in ILD by improving quality of life and dyspnea through education, exercise, and emotional support. Palliative care should be instituted promptly concurrent with selected drug treatments. Oxygen therapy should be prescribed if hypoxemia is detected with exercise or persists at rest. Treatment of comorbidities, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and COPD may reduce exacerbations of ILD.

Most importantly, referral and consultation with a pulmonologist is necessary when fiberoptic bronchoscopy is needed to rule out specific diseases, including sarcoidosis or eosinophilic granuloma, and to enroll patients in clinical drug trial for specific ILDs, particularly IPF, which carries a poorer prognosis3. UIP/IPF, unlike other IIPs, carry a poor prognosis with death likely to occur within 10 years after diagnosis if symptoms progressively worsen.

This long-known fact argues for early diagnosis of IPF and referral to a pulmonologist. However, the all-cause mortality is relatively low in patients presenting IPF with mild to moderate impairment of lung function.5 The FVC is the standard metric to follow and can determine eligibility for clinical trials. Indicators of longer survival among patients with IFP include younger age (<50 years), female gender, shorter period (≤1 year) with dyspnea and relatively preserved FVC, presence of ground glass and reticular opacities on HRCT.6

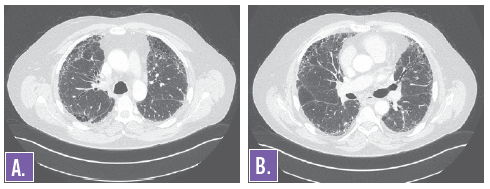

Figures 3A and 3B. HRCT of the chest showing diffuse interstitial markings consistent with chronic interstitial lung disease.

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of ILD should be made after no more than 3 weeks during the evaluation of chronic exertional dyspnea and dry cough. Do not rush to diagnose COPD in patients between the age of 40 and 70 years without confirming COPD with spirometry. Normal spirometry should raise the specter of ILD in patients with chronic, unexplained dyspnea. When considering ILD, obtain lung volumes and DLco when you discover there is little evidence for airway obstruction or FEV1/FVC is >0.70. Consultation with a pulmonologist experienced in the field should be made to confirm the diagnosis and explore new therapies. The clinical course of ILD varies considerably and depends greatly on the underlying condition or cause(s), control of comorbidities, and consideration of clinical drug trials. Prompt and correct classification and diagnosis of the underlying condition is essential to the source of ILD.

Chinh T. Phan, DO, is chief fellow in the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of California, Davis.

Samuel Louie, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, Department of Internal Medicine at the University of California, Davis.

References:

- Marelich GP, Louie S. Interstitial lung disease: what to cover in a brief visit. J Respir Dis. 1997;18:923-932.

- American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. International multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):277-304.

- Spagnola P, Tonelli R, Cocconelli E, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnostic pitfalls and therapeutic challenges. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;7(1):42.

- Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, et al. What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics. 2007;27(3):595-615.

- King TE, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. All cause mortality rate in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Implications for the design and execution of clinical trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(7):825-831.

- American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646-664.