Pediculosis Diagnosis and Management: Advice for Educating About the Facts of Lice

ABSTRACT: Because lice infestations cause so much anxiety among children, parents, educators, and even health care providers, it is vital for pediatricians to remain calm voices of reason and educate about lice in their communities. Lice infestation management goals include avoiding misdiagnosis, offering inexpensive and effective treatment options, and educating patients, parents, and school officials about a commonsense approach to outbreaks. This article reviews pediculosis epidemiology, pathophysiology and diagnosis, and discusses treatment options, including over-the-counter and prescription medications and nonpharmacologic approaches.

For insects that cause so little harm, head lice engender tremendous anxiety for children, parents, educators, and even health care providers. Many of us have worked with otherwise rational clinical colleagues who will scratch their bodies and scalps for the rest of the day after having seen lice or nits in a child’s hair. Recent reports of resistant “super bug” lice only fuel the fear.

It is vital for pediatricians and other primary care providers to remain the calm voices of reason and education in their communities. Avoiding misdiagnosis, offering inexpensive and effective treatment options, and continuing to fight “no nits” policies in schools are the goals of pediculosis management.

Epidemiology

Pediculus humanus capitis, better known as head lice, are found worldwide but cost the citizens of the United States an estimated $1 billion annually. Head lice most often infest children in preschool and elementary school, causing an estimated 6 million to 12 million infestations per year in this age group. In 1998 alone, 12 million to 24 million school days were lost due to policies that forbid children with observed nits from attending school. While industrialized countries typically have a 1% to 3% prevalence of lice, elementary schools can have a prevalence of up to 25%.

In contrast to body lice infestations, head lice infestations transcend socioeconomic boundaries. The louse most commonly is transmitted from direct hair-to-hair contact between an infested person and an uninfested person, although lice in rare cases can be transmitted via indirect contact by the sharing of hats or hair accessories. Lice seem to prefer fine, straight hair, although the insects can infest persons with all hair types. The direct contact is important: Head lice cannot fly or jump, they only can crawl. Moreover, they do not transmit other infectious diseases, and humans are their only host, so lice never are transmitted to people by pets or other animals.1-4

Pathophysiology

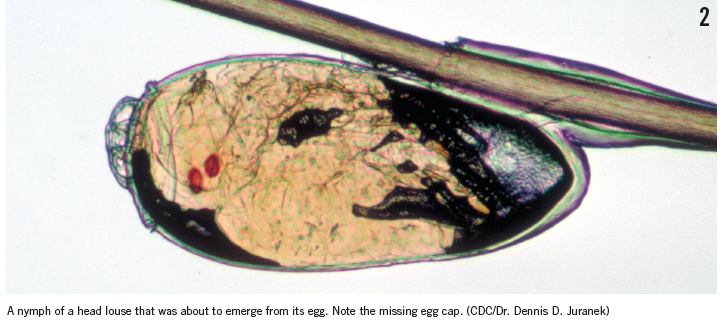

Knowing the basics about the louse’s life cycle helps parents and health care providers understand the treatment protocols for infestations. Newly laid eggs, called nits (Figures 1 and 2), take 7 to 10 days to hatch, during which time they must remain warm. Viable eggs are laid about 6 mm from the scalp on the hair shaft, although in extremely warm climates, nits may survive further away from the scalp. Generally, nits that are found more than 6 mm from the scalp either are empty egg cases or are nonviable (dead) eggs. After hatching, the young nymphs (which are the size of a pinhead) must feed on the blood of their host several times per day for 7 to 10 days and undergo 3 molts as they grow.

The larger adult lice (Figure 3) are about the size of a sesame seed, avoid the light, and move very quickly. They can be very hard to spot. Adult lice can stay alive on a human head for up to 30 days, and a single female louse can lay 8 to 10 nits per day. Interestingly, the adult louse’s color depends on its host’s hair color: Dark-haired hosts have darker lice, and light-haired hosts have lighter lice. Lice cannot survive for more than 2 days once separated from a host. Even if lice are still alive after that time, they are too weak to cause infestation.1,3,5

Symptoms often are absent until infestation is fairly heavy. The scratching that may bring attention to the problem often does not begin until the patient has been sensitized to the saliva the lice have injected into the scalp to aid in feeding, which takes 4 to 6 weeks for a new host. By then, hundreds of live lice may be present on one head. The scratching is more harmful to the patient than is the presence of lice, since resultant excoriations may become secondarily infected with bacteria.

Diagnosis of infestation

Visualization of head lice in the hair of a patient is diagnostic for infestation. If no lice are visualized, the presence of nits within 6 mm of the base of hair shafts is suggestive but not diagnostic of an active lice infestation. A Wood lamp may help easier visualize nits, which will fluoresce light blue. If no lice are seen, and nits are more than 6 mm from the hair shaft, the patient is not currently infested. However, a visual inspection alone is not sensitive enough for a definitive diagnosis.6 If infestation is suspected but no lice are visualized, either wet combing or dry combing with a fine-tooth comb is recommended to look for live lice.2 No head-to-head studies have shown wet or dry combing techniques as superior.3,6

The technique for parents or health care providers to detect or rule out an active lice infestation includes the following:

Remove all tangles from the hair first. Use an appropriate detection comb the teeth of which are between 0.2 and 0.3 mm apart. Name-brand combs can be relatively expensive, and a less-expensive flea-and-tick comb from a pet store meets this criterion and may be used. Place the detection comb near the crown until it lightly brushes the scalp, then firmly comb down to the ends of the hairs. After each stroke, inspect the comb for lice. Repeat this process systematically until all scalp hair has been combed through at least twice.3,4,6 Parents can place trapped lice in a sealed plastic bag and bring it to the clinic for confirmation. Most lice combed out of the hair in this fashion get damaged to the point of being nonviable.5

Treatment

Head lice are not a health hazard. Do not recommend pharmacologic treatment unless live lice have been identified. Neither the suspicion of live lice nor the presence of nits alone are indications for medical treatment. It is unwise to recommend treatment to parents over the phone, without having examined the child. Dandruff, lint, and hair casts can be misidentified as lice or nits, even by physicians.4

Nits are hard to remove and may be present for months following successful pharmacotherapy; their presence does not represent treatment failure. Once a person has been identified as having an active infestation head lice, advice about treatment can be offered for the person, as well as for the person’s bed partners and other members of the household who have been found to have live lice or nits within 1 cm of the scalp. All members of a household should be treated simultaneously to prevent reinfestation.

It is reasonable to simultaneously cleanse the fomites in the patient’s home to decrease risk of reinfestation. Only items that have been in extensive contact with the patient’s head in the prior 48 hours need to be cleaned. Hats and headgear, combs and brushes, hair accessories, bed linens, and bath towels are the most important items to clean. Temperatures greater than 54.5°C kill lice and nits, so washing the items in hot water in a washing machine, or soaking them in hot water for 5 to 10 minutes, or a 10-minute spin in a clothes dryer on high heat are generally effective. Dry cleaning also can be effective.

Vacuuming rugs and furniture where the patient plays frequently, as well as car seats, may be of some benefit, although lice do not remain viable for a significant time off their host. It probably is unnecessary, but a worried parent can seal anything that is not washable in a trash bag for 2 weeks, which is more than ample time to kill unhatched nits.3,7 Educate parents that nits do not hatch at room temperature, and that even if they did, the nymphs would have to find a host quickly or die.

The most important advice to a parent, regardless of the medication chosen, is to follow the treatment instructions precisely. The instructions for use may differ among different products. Moreover, fully saturating long, thick hair may require large amount of product. If parents have trouble understanding the medication’s package insert, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Web site offers application instructions for all of the lice treatments that have been cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).3 The accompanying Table2 summarizes the head lice treatments available in the United States.

Inform parents that most treatments cause some itching or burning of the scalp, particularly when the scalp is excoriated from scratching, but the discomfort only lasts for days and is not an indication for retreatment. This adverse effect can be treated with antihistamines or topical hydrocortisone if needed.

Retreatment always is necessary if the medication is only a pediculicide (ie, kills lice) but not an ovicide (ie, kills eggs). All patients need to be inspected with either wet combing or dry combing 7 to 9 days after treatment. Retreatment at 9 days generally is accepted as optimal for pediculicides if live lice are found at that point.

OTC Medications

Over-the-counter (OTC) treatments for head lice include permethrin and pyrethrins.

Permethrin. Permethrin cream, 1% (Nix), remains the pharmacologic treatment of choice. It is a well-studied pediculicide and is the least toxic to humans, and it is FDA-approved for children 2 months of age and older. Permethrin is a synthetic pyrethroid; parents who are concerned about exposing their children to artificial chemicals can be reminded that permethrin is an imitation of a chemical that occurs naturally in the chrysanthemum flower, but with the advantage that it does not cause an allergic reaction in those with plant sensitivities.7 Another of permethrin’s advantages is its relatively low cost.

Permethrin is neurotoxic to the hatched louse. It is not ovicidal. The medication clings to the washed hair shaft and thus also kills newly hatching nymphs over ensuing days. But because most other shampoos contain conditioners or silicone, this effect is diminished, and retreatment still is needed at 9 days to kill hatching nymphs.

Lice that have a DNA sequence with 2 specific genetic mutations, called the knockdown resistance–like or kdr gene, may be resistant to permethrin, and recent research suggests that kdr is a marker of treatment failure.8 However, the reliability of kdr as a marker of treatment failure is controversial. Researchers in Germany9 found that 93% of lice samples from across that country possessed the kdr gene; still, 93% of children whose lice carried kdr were treated successfully with permethrin lotion, 0.5%—a concentration half that of the permethrin cream sold in the United States. This finding suggests that the fear of widespread permethrin-resistant lice might be unfounded.

Prescription-strength permethrin, 5%, is FDA-approved as an anti-scabies medication, but it offers no increase in efficacy over the 1% concentration for the treatment of lice7 and is not FDA-approved for the indication.

Pyrethrins. Pyrethrins (chrysanthemum extract) also are neurotoxic to lice.2 Like permethrin, they are relatively inexpensive and have low toxicity to humans. Introduced in 1980s, pyrethrins are combined with piperonyl butoxide, which can potentiate the effect of pyrethrin and possibly impede the development of drug-resistant lice. There is some suggestion that certain formulations of the same pyrethrins are more effective in treating lice than others (eg, A-200 brand vs RID brand).1,7 Package labels warn against the use of pyrethrins in persons who are allergic to chrysanthemums or ragweed.1,7 Of note, pyrethroid-impregnated nets have been shown to reduce head lice incidence in refugee populations, in whom the mechanism of spread is thought to be family members sleeping in close proximity to each other.1

Some communities have higher reported rates of pyrethrin-resistant lice.10 Like permethrin, pyrethrins are not ovicidal and require at least 1 retreatment 9 days after the initial treatment.

Prescription Medications

A number of prescription-only topical head lice medications also are available, including benzyl alcohol, ivermectin, malathion, and spinosad. Lindane is no longer recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics due to central nervous system toxicity.2

Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol lotion, 5%, marketed in the United States as Ulesfia, works by asphyxiating live lice (but not nits). Benzyl alcohol forces louse spiracles open, allowing the inactive ingredients of the lotion to infiltrate them and induce suffocation.

Benzyl alcohol was FDA-approved in 2009 for the treatment of head lice in persons 6 months of age and older. In phase 3 clinical trials, it has been shown to be up to 76% effective 14 days after the final treatment.11,12 Retreatment is necessary if live lice are seen 7 to 9 days after the initial treatment.

Because this medication is not a pesticide, it has a niche for families with an aversion to pesticides and who can afford it. It is comparatively expensive, especially since a second treatment often is needed. And because its use has been associated with neonatal gasping syndrome, it should not be used in neonates.

Ivermectin. Ivermectin lotion, 0.5%, marketed as Sklice in the United States, is a frequently-used anthelmintic agent that acts to hyperpolarize chloride-ion channels in muscle cells, leading to the paralysis and death of live lice and the paralysis of oral feeding muscles in hatching nymphs, who then become nonviable and starve. It was FDA-approved in 2012 for the treatment of head lice in persons 6 months of age and older. Advantages include that only a single treatment is necessary. In 2 multisite, randomized, double-blind trials, a single topical application of ivermectin, 0.5%, was found to be approximately 74% effective 15 days after application.13 Ivermectin is a comparatively expensive lice treatment.

Malathion. Available in the U.S. market as Ovide, malathion lotion, 0.5%, is pediculicidal and ovicidal and has the highest infestation cure rate after a single treatment. It is an organophosphate insecticide, a cholinesterase inhibitor that is neurotoxic, causing paralysis and death of live lice and hatching nymphs.1 When used as directed, malathion is safe and effective14 and has been shown to have no impact on plasma or red blood cell cholinesterase concentrations.15

The malathion formulation prescribed in the United States differs from the one used for decades in other countries, particularly the United Kingdom, where some areas of high resistance among lice have been reported. Therefore, resistance rates reported for other countries are not applicable to the U.S. population. In the U.S. formulation, malathion is compounded with terpineol, dipentene, and pine needle oil, which have pediculicidal activity, with the hope that the formulation will delay the development of resistant lice. Malathion is FDA-approved for the treatment of head lice only in persons 6 years of age and older. It is contraindicated in persons younger than 2 years of age.

Parents who express concern about the neurologic impact of organophosphates can be assured that the concerns related to agricultural organophosphates likely do not apply to prescription malathion.15 While it is possible that any organophosphate could cause respiratory suppression if the medication is actually ingested, there have been no reports of this.5 Retreatment is required if live lice are seen on days 7 through 9 after the initial treatment with malathion

Malathion is comparatively expensive and is flammable (no smoking nearby).

Spinosad. The FDA in 2011 approved Spinosad suspension, 0.9% (Natroba), for the treatment of head lice. Spinosad is a combination of spinosyn A and spinosyn D, which are naturally fermented derivatives of the soil bacteria Saccharopolyspora spinosa.16 Spinosad was first developed as a broad-spectrum garden pesticide; it may or may not reassure parents to know that spinosad is given orally to cats and dogs to treat fleas. Spinosad induces neuronal hyperexcitation of both live lice and nits, leading to their death.

Spinosad is FDA-approved for the treatment of head lice in persons 6 months of age and older. No nit combing is necessary, and one treatment may suffice. Other advantages include that it has low mammalian toxicity, low rates of topical irritation, and low absorption through skin.

Two large phase 3, multicenter trials evaluated the efficacy of spinosad compared with that of permethrin. Success rates for spinosad—defined as a person being lice-free 14 days after the final treatment—were 84.6% in one study and 86.7% in the other, compared with 43% and 45%, respectively, for permethrin.2,17 While these study results are promising, the relatively very high cost of spinosad may be prohibitive.

Alternative Treatments

Occlusive agents. Many parents believe that certain alternative regimens are as effective as traditional pharmacotherapy for eliminating lice. These home remedies include mayonnaise, hair pomades, vinegar, and olive oil. While these treatments certainly are harmless, none have any true pediculicidal effect, although they may be useful in slowing down the lice to allow them to be carefully combed out, followed by manual removal of nits. It is worth noting that lice can live without oxygen for hours; during this time, they show no movement of any musculature, including respiratory muscles.1 It is likely that this total paralysis has led people to believe incorrectly that these treatments kill the lice.

A well-known occlusive home remedy, referred to as the Nuvo method, was developed by dermatologist Dale Pearlman, MD. Detailed instructions for this method of treatment can be found readily on the Internet. In essence, Cetaphil skin cleanser and a regular blow dryer are used presumably to smother and then desiccate the lice.18 Dimethicone, one of the ingredients in Cetaphil, has been demonstrated to have pediculicidal effect.19 Two uncontrolled studies conducted by Pearlman showed 96% efficacy in eliminating louse infestation after 3 weekly treatments. This method is not FDA-approved, but anecdotally, parents have used this method successfully. Encourage parents to consider an evidence-based, FDA-approved treatment if the Nuvo method is not successful, especially if the child is being held out of school because live lice or nits still are present.

Manual removal of lice and nits. This original treatment for head lice obviously is the safest, especially for infants, and still is a good option for those who have the patience and wish to avoid any and all chemicals. Wetting the hair and using a nit comb and a magnifying glass seem to make “nit picking” easier. Three weekly cycles of manual removal are needed. Manual nit removal can be added to any of the other treatment methods and may increase efficacy and reduce the psychosocial impact of infestation by eliminating the visible evidence.

“Natural” products. Encourage parents to be very skeptical of “natural” or herbal products sold online or in stores that are made with long lists of essential oils, plant products, and/or “enzymes” that are claimed to kill the louse or destroy the louse exoskeleton. None of these products are regulated by the FDA. (For example, one product sold online lists 16 different “active ingredients” and touts the fact that it is manufactured in an “FDA-approved lab,” which is misleading.) Herbal remedies are notorious for having highly variable content, and they may cause contact dermatitis or allergic reactions. If they are capable of dissolving the louse exoskeleton or nit glue, they also may dissolve some skin.

Tea tree oil in particular may have significant adverse effects. In pediatric patients, topical application of tea tree oil can lead to local allergic reactions, contact dermatitis, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and idiopathic male prepubertal gynecomastia.20 In the pediatric population, oral poisoning can lead to central nervous system depression, with somnolence and ataxia.

As with other drugs, herbal medications tend to have a greater effect in children than in adults due to children’s relatively lower body weight and more permeable skin.21 One or more of these plant products someday may prove to be a safe, cheap, and effective treatment, but it is best to counsel avoidance until there more controlled data exist.

Akshay Chaku is an MD candidate at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Leigh Ann Lather, MD, is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Virginia Children’s Hospital in Charlottesville, Virginia.

References

1. Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):1-12.

2. Eisenhower C, Farrington EA. Advancements in the treatment of head lice in pediatrics. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26(6):451-461.

3. Head lice. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head. Updated September 24, 2013. Accessed June 16, 2015.

4. Roberts RJ. Head lice. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1645-1650.

5. Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1355-e1365.

6. Mumcuoglu KY, Friger M, Ioffe-Uspensky I, Ben-Ishai F, Miller J. Louse comb versus direct visual examination for the diagnosis of head louse infestations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18(1):9-12.

7. Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):965-974.

8. Yoon KS, Previte DJ, Hodgdon HE, et al. Knockdown resistance allele frequencies in North American head louse (Anoplura: Pediculidae) populations. J Med Entomol. 2014;51(2):450-457.

9. Bialek R, Zelck UE, Fölster-Holst R. Permethrin treatment of head lice with knockdown resistance–like gene. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(4):386-387.

10. Burkhart CG. Relationship of treatment-resistant head lice to the safety and efficacy of pediculicides. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(5):661-666.

11. Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (Pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(1):19-24.

12. Ulesfia [package insert]. Bridgetown, Barbados: Concordia Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2013.

13. Pariser DM, Meinking TL, Bell M, Ryan WG. Topical 0.5% ivermectin lotion for treatment of head lice. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(18):1687-1893.

14. Roberts RJ, Casey D, Morgan DA, Petrovic M. Comparison of wet combing with malathion for treatment of head lice in the UK: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000 Aug 12;356(9229):540-544.

15. Dennis GA, Lee PN. A phase I volunteer study to establish the degree of absorption and effect on cholinesterase activity of four head lice preparations containing malathion. Clin Drug Invest. 1999;18(2):105-115.

16. Natroba [package insert]. Carmel, IN: ParaPRO LLC; 2011.

17. Stough D, Shellabarger S, Quiring J, Gabrielsen AA Jr. Efficacy and safety of spinosad and permethrin creme rinses for pediculosis capitis (head lice). Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e389-e395.

18. Pearlman DL. A simple treatment for head lice: dry-on, suffocation-based pediculicide. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e275-e279.

19. Burgess IF, Brown CM, Lee PN. Treatment of head louse infestation with 4% dimeticone lotion: randomised controlled equivalence trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7505):1423.

20. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, Kazerouni A. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(7):784-790.

21. Hammer KA, Carson CF, Riley TV, Nielsen JB. A review of the toxicity of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44(5):616-625.