Opioids With Abuse-Deterrent Technologies: What Role Do They Play in Managing Chronic Pain in Older Adults?

Key words: Abuse-deterrent technologies, chronic pain, drug diversion, opioid abuse, opioid analgesics, opioid misuse.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

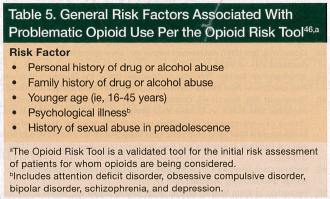

Chronic pain is common in older adults, with studies indicating its presence in up to half of this population.1-3 It is well established that opioid analgesics are an essential component of a multimodal strategy in the management of chronic pain in properly selected older patients,4 but abuse, misuse, and diversion of opioids are a growing problem in the United States (Table). Therefore, the risk of abuse, misuse, and diversion needs to be carefully balanced with the need for adequate pain treatment, keeping in mind that inadequate pain control is associated with adverse outcomes. Abuse may become a concern in patients who use opioids for an extended period of time for pain management or who have a personal, family, or caregiver history of abusing tobacco, alcohol, or other substances.

Chronic pain is common in older adults, with studies indicating its presence in up to half of this population.1-3 It is well established that opioid analgesics are an essential component of a multimodal strategy in the management of chronic pain in properly selected older patients,4 but abuse, misuse, and diversion of opioids are a growing problem in the United States (Table). Therefore, the risk of abuse, misuse, and diversion needs to be carefully balanced with the need for adequate pain treatment, keeping in mind that inadequate pain control is associated with adverse outcomes. Abuse may become a concern in patients who use opioids for an extended period of time for pain management or who have a personal, family, or caregiver history of abusing tobacco, alcohol, or other substances.

Abuse, particularly with long-acting and extended-release (ER) opioids, has been targeted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to the disproportionate safety problem conferred by these formulations compared with short-acting or immediate-release opioids, and the development of opioids with abuse-deterrent technologies (ADTs) has been encouraged.8 The ER opioid products contain a large amount of opioid in each dose, making them appealing products for abusers.9-11 While abuse of opioids often begins with oral ingestion, it can advance to other routes of administration to achieve a quicker onset of action. Abusers often manipulate ER opioid formulations to enable these agents to be snorted, smoked, or injected. Prescription opioid diversion and misuse present additional concerns. It has been postulated that the advent of ADTs may play a role in decreasing the incidence of opioid abuse or misuse.9,10 We examine the prevalence of opioid abuse and misuse among older adults, costs associated with such acts, and the practical implications and challenges of prescribing opioid-based ADTs to this population.

Data on Abuse and Misuse of Opioids Among Elders

Use of substances, including prescription pain medications, among middle-aged and older adults is predicted to increase over time as the baby boomer population (ie, those born from 1946-1964) continues to age.2,12 Data demonstrate that illicit drug use in the United States was rare in the generation that preceded the baby boomer group and that baby boomers have an increased propensity to use illicit drugs.13,14 This information, coupled with the fact that the baby boomer generation is larger than any previous generation, suggests that the prevalence of substance abuse among older adults may increase as this generation ages. When the baby boomers started turning 65 years old in 2011, 10,000 people started turning 65 years of age every day and will continue to do so for the next 20 years.15 All of this age group will be at least 50 years of age in 2020 and at least 65 years of age in 2030.13,14 This means that by 2030, almost one of every five Americans—an estimated 72 million people—will be at least 65 years of age.15

While misuse and abuse may currently be less likely among elders, there is evidence of misuse and abuse in this patient population. In a national survey conducted between 2005 and 2006 that included a representative sample of middle-aged and older adults (aged ≥50 years, with approximately 40% aged ≥65 years), approximately 1.4% of respondents (n=155) reported nonprescription use of prescription pain relievers within the past 12 months of being interviewed.2 A total of 1.9% of respondents aged 50 to 64 years and 0.6% of those aged 65 years and older reported nonmedical use of prescription pain killers. Propoxyphene, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and codeine products were the most commonly used. In the subsample of nonprescription users (n=155), 1.7% met criteria for abuse within the past 12 months.2

In a retrospective cohort study that included outpatients aged 65 years and older who were newly started on an opioid for chronic noncancer pain (n=33), a total of 3% of patients displayed behaviors consistent with abuse or misuse.16 Another study that assessed opioid misuse in community-dwelling older adults (≥65 years of age) found that higher levels of pain severity, presence of depressive symptoms, and lower physical disability scores were significantly associated with increased risk of opioid misuse.17 This study defined misuse as overuse or inappropriate use (ie, borrowing or hoarding medications, unauthorized dosage increases, early refills, or unintended use for hypnotic effects or to treat anxiety). In 2009, a small pilot study conducted in Wilmington, Delaware, suggested that elders are one of the primary sources of prescription drug medications sold on the street.18

Costs of Abuse and Misuse of Prescription Opioids

There are many costs associated with abuse and misuse of prescription opioids. The cost of drug diversion to insurance plans has been conservatively estimated to reach $72.5 billion per year.19 This estimate includes the price of treating conditions that develop as a result of abusing opioids obtained through diversion, but it does not include the costs of abuse and misuse that result from overdoses that require emergency department (ED) visits. These costs are bound to be quite high, as demonstrated by the following data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention20,21 and the US Department of Health and Human Services22:

• Of the 20,044 deaths that occurred from prescription drugs in 2008, 14,800 (73.8%) involved opioid analgesics.20 Opioid analgesic overdose death rates were highest among persons aged 35 to 54 years.

• In 2008, the age-adjusted death rate for opioid analgesic overdose was 1.0 per 100,000 for persons 65 years of age and older versus 4.8 per 100,000 for all age groups combined.20

• In 2009, opioid analgesics accounted for 31.7% of ED visits involving nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals, with 7.7% of these cases occurring in patients aged 65 years and older.22

• The estimated number of ED visits involving nonmedical use of opioid analgesics increased from 144,644 in 2004 to 342,628 in 2009, representing a 137% increase.21,22 In 2009, ED visits for opioid analgesics were highest for oxycodone (148,449), hydrocodone (86,258), and methadone (63,031).22

Government Action

Prescription drug abuse has been identified as the most rapidly escalating drug problem in the United States.8 Because of the high risk of death associated with abusing prescription opioids, these agents are being more heavily regulated by the FDA. While the FDA strives to ensure that patients with a need for prescription opioids continue to have appropriate access to them, the goal is to minimize the potential for individuals to abuse and misuse these agents. To balance the benefits and risks of opioids, enabling patients suffering from pain to receive relief while reducing the opportunity for inappropriate use and diversion, the FDA developed a Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan.23,24 This plan focuses on four areas to decrease opioid abuse: education, monitoring, proper disposal, and enforcement. It also encourages manufacturers to develop opioid products with abuse deterrents.

The education initiative of the Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan includes information on the opioid risk evaluation and mitigation strategy to train prescribers on appropriate opioid use. Prescriber education includes information on weighing the risks and benefits of opioid therapy, choosing patients appropriately, monitoring patients, and counseling patients on the safe use of these drugs.23,24 In addition, prescribers are educated on how to recognize evidence of and potential for opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction. To track and monitor opioid abuse, many states have developed prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).8 These programs are authorized by the legislature of the respective states and are able to monitor opioid prescriptions dispensed statewide. Although these programs have the potential to assist with identification of fraud and diversion, the role of PDMPs is still evolving. Because many patients have opioid prescriptions at home that are unwanted or unneeded, these medications may be diverted into the community and used inappropriately; therefore, initiatives are underway to establish proper methods for disposal of unused and expired prescription medications. Law enforcement will continue to play a role in fighting opioid abuse.

Abuse-Deterrent Technologies

The purpose of ADTs is to ensure that patients with a valid medical need have access to opioids, while at the same time preventing these agents from being used illicitly.25 In the literature, terms such as tamper-resistant, abuse-resistant, and abuse-deterrent have been used to label opioid formulations that employ methods for preventing abuse and misuse; however, these terms have not been applied uniformly. In Guidance for Industry: Assessment of Abuse Potential of Drugs,25 the FDA defined the concept of abuse deterrence as a formulation with “limits or impediments to abuse.” Therefore, for the purpose of this article, abuse-deterrent opioids will be used as a general term to define any change in the formulation designed to limit abuse or misuse of the respective opioid drug. Examples of abuse-deterrent products include those that have a physical or chemical barrier that prevents tampering, are agonist-antagonist combination products, or contain noxious substances (Table 2). Other ADTs, including prodrugs, are in development. Most opioids that use ADTs are submitted for approval based on previous evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of the opioid, with additional supporting data for the ADT.26 Thus far, the FDA has not allowed any claims of abuse resistance or abuse deterrence to be used in the product labeling of any opioid products implementing an ADT.26 Nevertheless, the FDA continues to encourage the development of abuse-deterrent opioid products.26,29 Any change in the labeling of opioid products to indicate ADT effectiveness is dependent upon long-term epidemiological studies demonstrating these products to reduce the incidence of abuse. Long-term community-based results are not yet available. In the meantime, the FDA does allow manufacturers to include data on the drug labeling information that support an individual opioid’s resistance to manipulation.30 The label also includes factual information about studies that relate to the agent’s abuse liability (ie, the propensity of a particular psychoactive substance to be susceptible to abuse), such as diversion.

As shown by Table 2, an assortment of strategies have been applied or are in development with regard to abuse-deterrent opioid formulations. A physical barrier can be used to overcome manipulation of the opioid formulation, making tampering with the product’s dosage difficult.9 This strategy was employed when oxycodone ER was reformulated in 2010 to create a pill that is bioequivalent to the original formulation, but more resistant to abuse and misuse due to tampering via chewing, crushing, cutting, or otherwise breaking the tablets.31 The reformulated oxycodone tablets contain polyethylene oxide; thus, when the tablets are dissolved in liquid, a viscous substance is formed that makes it too thick to snort or inject.31,32

As shown by Table 2, an assortment of strategies have been applied or are in development with regard to abuse-deterrent opioid formulations. A physical barrier can be used to overcome manipulation of the opioid formulation, making tampering with the product’s dosage difficult.9 This strategy was employed when oxycodone ER was reformulated in 2010 to create a pill that is bioequivalent to the original formulation, but more resistant to abuse and misuse due to tampering via chewing, crushing, cutting, or otherwise breaking the tablets.31 The reformulated oxycodone tablets contain polyethylene oxide; thus, when the tablets are dissolved in liquid, a viscous substance is formed that makes it too thick to snort or inject.31,32

Agonist-antagonist combinations have been developed to decrease the incidence of tampering via chewing and swallowing or by crushing and snorting or injecting an opioid.10,26 In these combination products, an opioid acts as the agonist, and an opioid antagonist (eg, naloxone, naltrexone) is added to regulate use of the product. If the opioid antagonist is released from the dosage form or is otherwise activated, the antagonist binds to the opioid receptors and does not allow the patient to experience the desired effect from the opioid (eg, euphoria). This concept was used with Talwin Nx and Suboxone, which added naloxone to pentazocine and buprenorphine, respectively.29,33 Naloxone only has activity when injected; therefore, it only deters abuse by neutralizing the effect of these opioids when they are crushed and injected. More recently, an ER morphine formulation with a sequestered inner core of naltrexone (Embeda) was approved.29,34 When these ER capsules are swallowed whole or administered as a sprinkle, morphine is released over 24 hours and the naltrexone remains sequestered in the inner core33,34; however, if an attempt to tamper with the dosage form is made (eg, by crushing), naltrexone and morphine are released, and if the tampered product is ingested, naltrexone competitively binds at the µ-opioid receptors and blocks the euphoric effect of morphine.35 In an opioid-tolerant person, opioid withdrawal may occur.34

It has been theorized that abuse may be deterred if a noxious substance is added to an opioid.10,26 The thought is that the opioid and noxious substance combination is less likely to be abused due to adverse effects suffered as a result of consuming excess quantities of the noxious substance when the opioid is taken other than as directed.10 Niacin has been evaluated in combination with immediate-release oxycodone (Acurox) for this purpose. Each Acurox tablet contained subtherapeutic levels of niacin and was designed so that patients taking more than the prescribed number of tablets would experience adverse effects, such as flushing, due to the consumption of niacin.32 This formulation did not receive FDA approval because the addition of niacin was found to have minimal abuse-deterrent potential. However, Acurox contained other compounds that deterred abuse, including sodium lauryl sulfate, which causes burning and irritation of the nasal passageways if crushed and snorted, and polyethylene oxide, which deters use via intravenous injection or snorting because it forms a viscous substance when dissolved in liquid.32,36 In June 2011, a reformulated version of Acurox that did not contain niacin was approved by the FDA under the tradename Oxecta.36,37

Prodrugs are also under development.27 These products require activation in the gastrointestinal tract; therefore, an abuser would not experience euphoria if the prodrug is tampered with and then injected, smoked, or snorted. Additionally, many other opioid products are in development using a variety of technologies in an attempt to make the respective opioid products less appealing for abusers. Table 3 provides a list of select opioid products using ADTs that have been developed or are under development.

Patent Implications of Abuse-Deterrent Technologies

Branded drugs that use ADTs have additional patent protection on the technologies being implemented to prevent abuse; thus, these products have an increased cost over their generic equivalents.43 The patent on an ADT is valid for up to 20 years from the date it is filed. Therefore, any generic formulation using an ADT must demonstrate interchangeability with the respective branded opioid via a technology that does not infringe upon the branded drug’s patent. Eventually, the FDA may develop guidance for manufacturers to follow to prove tamper- or abuse-deterrence, but even if such guidance is eventually provided, it is likely that it will remain costly for manufacturers to develop ADTs. In addition, it is probable that manufacturers will have to continue to navigate through the various patents on opioids, a difficult and time-consuming endeavor. As a result, immediate widespread prescribing of opioids that use ADTs would be expected to result in higher drug costs compared with the use of currently available generic opioid products (see cost comparison in Table 4). These increased costs would be incurred without any expectation of increased pain relief for patients or any epidemiological data to support the abuse-deterrent effects of new products manufactured with abuse deterrents.27 While abuse-deterrent opioids are of potential value for patients who are suspected of or at high risk of tampering or diversion (Table 5), the benefit is unclear in many elderly patients who are not at risk of opioid abuse, misuse, or diversion.4

Guidelines

Numerous published guidelines and statements from state medical boards mention the use of opioid analgesics for the management of pain and provide guidance on assessing and monitoring patients with chronic pain for appropriate opioid use.4,46-58 However, the most recent guidelines on pain management from the American Geriatrics Society (AGS; updated in 2009),4 American Pain Society (updated in 2008),47 the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (updated in 2010),48 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (updated in 2011)49 do not mention abuse-deterrent formulations in their pain management recommendations. The AGS guidelines do address opioid use specific to the elderly population, noting that while opioid misuse and abuse is less likely to occur in these patients, clinicians should prescribe opioids with caution to all patients, as the potential of diversion, misuse, or abuse of opioids does not dissipate with age.

Numerous published guidelines and statements from state medical boards mention the use of opioid analgesics for the management of pain and provide guidance on assessing and monitoring patients with chronic pain for appropriate opioid use.4,46-58 However, the most recent guidelines on pain management from the American Geriatrics Society (AGS; updated in 2009),4 American Pain Society (updated in 2008),47 the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (updated in 2010),48 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (updated in 2011)49 do not mention abuse-deterrent formulations in their pain management recommendations. The AGS guidelines do address opioid use specific to the elderly population, noting that while opioid misuse and abuse is less likely to occur in these patients, clinicians should prescribe opioids with caution to all patients, as the potential of diversion, misuse, or abuse of opioids does not dissipate with age.

Conclusion

The FDA is taking an aggressive stance to reduce the abuse, misuse, and diversion of prescription opioids. Although ADTs are a key element in this initiative, and the FDA has approved several opioid products that contain ADTs, it is notable that the FDA has not allowed any of these products to be marketed with claims of abuse-resistance or abuse-deterrence. This is likely because there are no studies yet to show that these formulations conclusively reduce the incidence of abuse, misuse, and deterrence, and because ADTs are currently unable to completely eliminate the potential for these acts. For example, patients may engage in unauthorized dose escalation via oral consumption or divert their medications to others.

Currently, ADTs mainly thwart the ability of individuals to modify opioids into forms that exacerbate the drugs’ effects (ie, snortable, injectable, smokable substances). Therefore, until the benefits of ADTs become known, patient selection for prescribing opioids with abuse-deterrent properties is imperative, including in the elderly population. The use of these agents should be restricted to patients with known risk factors for opioid abuse, misuse, or diversion, including those who have caregivers with known risk factors for opioid abuse or have close contact with individuals known to have engaged in or are suspected of engaging in diversion.

To prevent the unnecessary prescribing of opioids with ADTs, prescribers should carefully assess patients for risk factors that may predispose them to abusing opioids (Table 5). They should also ascertain which opioids and analgesics patients are currently using and how they are using them. This is especially important because opioids that incorporate ADTs have increased treatment costs, yet have no added benefit when prescribed to elderly patients who do not abuse, misuse, or divert these agents. In addition, increased costs may result in patients discontinuing treatment, leading them to experience uncontrolled pain. Balancing pain control while preventing abuse is imperative, and to achieve this objective, clinicians must continue to use their clinical judgment on a case-by-case basis.

References

1. Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR, Turner BJ, et al. Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1353-1369.

2. Blazer DG, Wu LT. Non-prescription use of pain relievers among middle aged and elderly community adults: national survey on drug use and health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1252-1257.

3. Pergolizzi J, Böger RH, Budd K, et al. Opioids in the management of chronic severe pain in the elderly: consensus statement of an international expert panel with focus on the six clinically most often used World Health Organization step III opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone). Pain Pract. 2008;8(4):287-313.

4. American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. Pain Med. 2009;10(6):1062-1083.

5. Budman SH, Grimes Serrano JM, Butler SF. Can abuse deterrent formulations make a difference? Expectation and speculation. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6:8.

6. Katz N. Abuse-deterrent opioid formulations: are they a pipe dream? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10(1):11-18.

7. Webster L, St Marie B, McCarberg B, et al. Current status and evolving role of abuse-deterrent opioids in managing patients with chronic pain. J Opioid Manag. 2011;7(3):235-245.

8. Epidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. Office of the President of the United States. 2011. www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/rx_abuse_plan.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

9. Webster L. Update on abuse-resistant and abuse-deterrent approaches to opioid formulations. Pain Med. 2009;10(suppl 2):S124-S133.

10. Tolliver JM; US Food and Drug Administration. Premarketing assessment of abuse deterrent formulations. October 21, 2010. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM233240.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

11. Sloan P, Babul N. Extended-release opioids for the management of chronic non-malignant pain. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3(4):489-497.

12. Kalapatapu RK, Sullivan MA. Prescription use disorders in older adults. Am J Addict. 2010;19(6):515-522.

13. Colliver JD, Comptom WM, Gfroerer JC, Condon T. Projecting drug use among aging baby boomers in 2020. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(4):257-265.

14. Gfroerer J, Penne M, Pemberton M, Folsom R. Substance abuse treatment need among older adults in 2020: the impact of the aging baby-boom cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69(2):127-135.

15. Alliance for Aging Research. Preparing for the silver tsunami. 2006. www.aging

research.org/content/article/detail/826. Accessed June 6, 2012.

16. Reid MC, Henderson CR, Papaleontious M, et al. Characteristics of older adults receiving opioids in primary care: treatment duration and outcomes. Pain Med. 2010;11(7):1063-1071.

17. Park J, Lavin R. Risk factors associated with opioid medication misuse in community-dwelling older adults with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(8):647-655.

18. Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Beard RA. Prescription opioid abuse and diversion in an urban community: the results of an ultra-rapid assessment. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):537-548.

19. Mahon WJ; Coalition Against Insurance Fraud. Prescription for peril: how insurance fraud finances theft and abuse of addictive prescription drugs. December 2007. www.insurancefraud.org/downloads/drugDiversion.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers–United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs–United States, 2004-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(23):705-709.

22. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; US Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2009: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. 2011. www.samhsa.gov/data/2k11/DAWN/2k9DAWNED/PDF/DAWN2k9ED.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

23. US Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers: FDA requires a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for long-acting and extended-release opioids. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251752.htm. Published April 19, 2011. Accessed June 6, 2012.

24. US Food and Drug Administration. List of long-acting and extended-release opioid products required to have an opioid REMS. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251735.htm. Updated November 4, 2011. Accessed June 6, 2012.

25. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: assessment of abuse potential of drugs [draft guidance]. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM198650.pdf. Published January 2010. Accessed June 6, 2012.

26. Rappaport BA; US Food and Drug Administration. Regulatory issues in reviewing and approving opioid analgesics. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM163692.pdf. Published February 10, 2009. Accessed June 6, 2012.

27. Pain Live. Abuse-deterrent technologies in opioid medications: a new weapon in the fight against misuse and abuse. www.painlive.com/publications/pain-management/2011/december-2011/Abuse-deterrent-Technologies-in-Opioid-Medications-A-New-Weapon-in-the-Fight-against-Misuse-and-Abuse. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed June 6, 2012.

28. KemPharm Inc. Ligand activated therapy. www.kempharm.com/lat.html. Accessed June 6, 2012.

29. Lapteva L; US Food and Drug Administration. Regulatory history of development of abuse-deterrent formulations. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM233240.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

30. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Division of Anesthesia and Analgesia. Advisory committee meeting background package. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM209141.pdf. Published April 22, 2010. Accessed June 6, 2012.

31. Purdue Pharmaceuticals. FDA Advisory Committee on Reformulated OxyContin. Public session September 24, 2009. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM249272.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

32. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new formulation for OxyContin [news release]. www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm207480.htm. Published April 5, 2010. Accessed June 6, 2012.

33. Pucino F; US Food and Drug Administration. History of “abuse-deterrent” combination opioids. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM210854.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

34. Embeda [package insert]. Bristol, TN: King Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2009.

35. Mehta H; US Food and Drug Administration. Outpatient drug utilization patterns for oxycodone-containing products in the US, years 2005-2009. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM210854.pdf. Published April 2010. Accessed June 6, 2012.

36. Oxecta [package insert]. Bristol, TN: King Pharmaceuticals Inc; June 2011.

37. Oxecta [data on file]. Bristol, TN: King Pharmaceuticals Inc; Received July 11, 2011.

38. Talwin Nx tablets [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; February 2011.

39. Suboxone sublingual tablets [package insert]. Richmond, VA: Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012.

40. Embeda. Important information for patients and prescribers. 2011. www.embeda.com. Accessed June 6, 2012.

41. Opana ER tablets [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2011.

42. Exalgo extended release tablets [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt; 2010.

43. Brushwood DB, Rich BA, Coleman JJ, Bolen J, Wong W. Legal liability perspectives on abuse-deterrent opioids in the treatment of chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010;24(4):333-348.

44. Clinical Pharmacology [online database]. Tampa, FL: Elsevier Gold Standard; 2012. www.clinicalpharmacology-ip.com/default.aspx. Accessed July 10, 2012.

45. First Databank [online database]. San Francisco, CA: FDB Solutions; July 6, 2012. www.fdbhealth.com. Accessed July 10, 2012.

46. Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) Assessment instrument. www.opioidrisk.com/node/887. Accessed July 11, 2012.

47. American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. 6th ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2008:18-52.

48. Rosenquist RW, Benzon HT, Connis RT, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on chronic pain management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(4):810-833.

49. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. www.nccn.org. Accessed April 17, 2012.

50. Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States Inc. Model policy for the use of controlled substances for the treatment of pain. www.fsmb.org/pdf/2004_grpol_Controlled_Substances.pdf. Published May 2004. Accessed June 6, 2012.

51. Trescot AM, Helm S, Hansen H, et al. Opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians’ (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2008;11(suppl 2):S5-S62.

52. American Pain Society. Guideline for the Management of Pain in Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis and Juvenile Chronic Arthritis. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: American Pain Society; 2002.

53. Miaskowski C; American Pain Society. Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Children. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2005.

54. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(2):137-162.

55. Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow VK, et al; Clinical Efficacy Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(3):247-248]. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491.

56. American Pain Society. Guideline for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. www.ampainsoc.org/pub/pdf/Opioid_Final_Evidence_Report.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

57. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al; American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113-130.

58. Webster L. Opioid risk tool. www.partnersagainstpain.com/printouts/Opioid_Risk_Tool.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012.

Article series summary:

This is the first article in a continuing series on pain management in older adults. Subsequent articles in this series will discuss pain management for elders with advanced illness, management of musculoskeletal pain in elders, and palliative care in older adults with acute and chronic cancer pain. These articles will be published in future issues of Clinical Geriatrics®.

Disclosures:

All authors are employed by and have stock ownership in Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefit manager. The series editor reports no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Andrew Behm, PharmD, CGP

Express Scripts

6625 West 78th Street

Bloomington, MN 55439

andrew.behm@express-scripts.com