The Lanolin-Wool Wax Alcohol Update

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can be separated into 2 main categories based on the type of exposure: irritant or allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is the most common cause of contact dermatitis and may occur in anyone who is exposed to the irritant with significant duration or in significant concentrations. Common irritants include chronic or frequent water exposure, abrasive cleansers, detergents, and soaps. It is important to note that ICD can at times precede or be a concomitant diagnosis with ACD.1,2

The most common sites of ACD are those with the most common contact with the allergen-containing topical products or source, such as the hands, face, and scalp, though any body region may preferentially develop an ACD reaction, or ICD for that matter. At times, another primary dermatosis is present and an ACD occurs as a secondary phenomenon due to symptomatic treatment with a myriad of topical products, as can occur with lanolin.

Confirmatory diagnosis of ACD is through the use of the epicutaneous patch test procedure. Once a patient’s spectrum of allergy is defined, education regarding their specific set of chemicals and products to avoid is of the utmost importance. Although ACD is not “curable,” many individuals will achieve complete remission with assiduous avoidance. ICD, on the other hand, does not have a specific diagnostic procedure, but it is “curable” through complete avoidance of the inciting agent(s). Correct identification of ACD and/or ICD is essential for successful long-term management of dermatitis. This article highlights ACD and explores top relevant allergens, regional-based dermatitis presentations, topic-based dermatitis presentations, as well as clinical tips and pearls for diagnosis and treatment.

Focus on Lanolin

The history of “wool wax” dates back several thousand years to the ancient Greeks, who were the first to recognize that water in which wool had been washed contained a valuable oilated substance. That substance, wool wax, derived from the sebaceous glands of sheep was found to be an outstanding emollient. It was referred to by several names including Hyssopus, Oesypum, and the most common form, Oesypus.

Over time, refining methods for “purifying” lanolin were developed. Early on, the extraction process of wool wax was simply a version of the modern foam flotation process. The wool washings were poured from a height into a receptacle, so that the wool wax formed as a froth-foam that could then be skimmed off and allowed to collapse, separating the wool wax to the surface. Technical advancements included acid cracking, which destabilized and separated the wax into a lower sludge state that could be filtered, and a method based on the addition of metals in the trivalent state to cause wax coagulation. It was the centrifugal separator that brought the extraction procedure into the new millennium, which has remained the preferred modern method of extraction.3

How It Is Used

Lanolin is routinely found in a wide range of products from metal lubricants and rust preventers to skincare emollient, wound care products, and a vehicle for topical therapeutics (Table 1). This has lead to lanolin making the “A-List” for top allergens.4,5

Sensitization And Testing

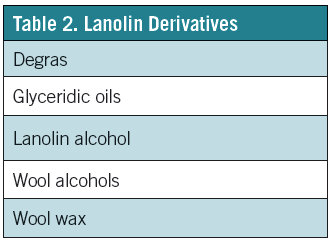

Lanolin continues to be a significant sensitizer. Specifically, there is a high prevalence of delayed-typed hypersensitivity to lanolin in patch tested pediatric populations.6 Also, there are a number of factors, which can affect the ability to properly gauge the frequency of sensitization. One factor is that lanolin is a bio-product whose lipid composition may vary based on the origin of the product; for example, the type of sheep and their habitat.7 Furthermore, several lanolin derivatives exist which further confound the difficulty in identifying the responsible component (Table 2). False negative reactions may occur on intact skin. Both contribute to what is known as the “lanolin paradox.”4,8

Notably, Matiz et al reported 2 patients who had negative reactions to the commercially prepared lanolin preparations (Thin-layer Rapid-Use Epicutaneous Test [Allerderm] and Allergeaze [Allergens]), but positive reactions to the lanolin 30% in petrolatum attained from Beiersdorf, in addition to the patient’s own Aquaphor healing ointment (AHO) product.9 Testing with the patient’s own products, at the same time as patch testing lanolin 30% in petrolatum and amerchol L101 50% petrolatum may be necessary to rule out lanolin causation of ACD.2

Furthermore, Miest et al discuss the fact that “the exact frequency of adverse reactions to lanolin in the general population is difficult to assess because most individuals with such reactions simply discontinue use of the suspected trigger and seldom consult physicians. In addition, proponents of lanolin as a relevant allergen suspect that contact allergy to lanolin is underdiagnosed because clinicians are not testing with the appropriate type or number of lanolin derivatives.”7

Practicals of Patch Testing

Practicals of Patch Testing

As discussed, patch testing is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of ACD and to identify the relevant allergen(s) responsible. Screening patch test trays isolate the most common chemicals and offer the provider clues for potential sources. The American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) North American Standard Series includes allergens from several different categories, which are available to healthcare providers;10 however, supplemental trays are also available.11

The idea behind using supplemental allergens is that by including constituents and cross-reactors of the allergen in question, the chance of demonstrating a relevant positive reaction is greater.12 In summary, these chemicals and products may overcome a threshold for reactivity.

Pearls of Treatment: Every Dose Counts

A person might be exposed to and subsequently sensitized to a contact allergen (eg, a fragrance) for days to years before demonstrating the clinical picture of ACD. With each exposure, there is an increased risk of reaching a point at which the immune system meets its metaphorical “threshold” and subsequent exposures can lead to elicitation of a cutaneous response.13 Just as repeated contact over time led to this immune response, repeated avoidance of the majority of exposures over time will be required to induce remission.

Avoidance of specific allergens in personal care products can prove to be a tedious task; however, there are programs available to aid in this endeavor. Both the Contact Allergen Management Program, a service offered through the ACDS,14 and the Contact Allergen Replacement Database, developed by Mayo Clinic,15 allow for a provider to enter a patient’s known contact allergens and produce a “shopping list” of products void of those particular chemicals. The programs also can exclude cross-reactors. Additionally, education for patients can be accessed through online programs, such as mypatchlink.com16,17 and through the ACDS website. ■

This article originally ran in the February 2014 issue of The Dermatologist.

Susan Jacob, MD, is a pediatric contact dermatitis specialist at Rady Children’s Hospital–UCSD in San Diego, CA.

References:

1. Nijhawen RI, Matiz C, Jacob SE. Contact dermatitis: from basics to allegodromes. Pediatr Annals. 2009;38(2):99-108.

2. Militello G, Jacob SE, Crawford GH. Allergic contact dermatitis in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(4):385-390.

3. Hoppe U. The Lanolin Book. Hamburg, Germany: Beiersdorf AG; 1999.

4. Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19(2):63-72.

5. Pasche-Koo F, Piletta PA, Hunziker N, Hauser C. High sensitization rate to emulsifiers in patients with chronic leg ulcers. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31(4):226-228.

6. Zug KA, McGinley-Smith D, Warshaw EM, et al. Contact allergy in children referred for patch testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2004. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(10):

1329-1336.

7. Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chung YH, Singh N. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24(3):119-123.

8. Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192(3):198-202.

9. Matiz C, Jacob SE. The lanolin paradox revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):197.

10. allergEAZE Allergens website. www.allergeaze.com/allergens.aspx?ID=Series. Accessed January 28, 2014.

11. Patch Test Products 2011. Chemotechnique Diagnostics 2011. www.chemotechnique.se. Accessed on January 30, 2014.

12. Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE. Patch testing: the whole in addition to the sum of its part is greatest. Dermatitis. 2009;20(1):58-59.

13. Jacob SE, Herro EM, Taylor J. Contact dermatitis: diagnosis and therapy. In: Elzouki AY, Harfi HA, Nazer HM, Bruder Stapleton F, Oh W, Whitley RJ, eds. Textbook of Clinical Pediatrics. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2012.

14. ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis website. www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed January 28, 2014.

15. Contact Allergen Replacement Database website. http://www.preventice.com/card/. Accessed January 28, 2014.

16. Wool Alcohols (Lanolin). MyPatchLink website. www.mypatchlink.com/pdf/wool_ alcohol.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2014.

17. Lanolin (Wool Wax Alcohols). MyPatchLink website. www.mypatchlink.com/allergen.aspx?ID=19. Accessed January 28, 2014.