An Intriguing Granulomatous Uveitis Case

A 29-year-old Indian female with a past medical history of right cervical tuberculosis (TB) lymphadenitis was referred to our clinic from ophthalmology for worsening uveitis. The patient had previously presented with a swelling on the right side of her neck of 2-week duration. At that time, she was 26 weeks pregnant and had no other symptoms except for constipation.

Physical Examination

The physical examination was remarkable for tender and indurated swelling on the right side of her neck below the mandibular angle; the size not given. Fetal echocardiogram was normal. The complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin clavulanate and lactulose, and was advised to return to clinic if the swelling persists.

The swelling did persist for 1-month despite antibiotics.

Figure 1. Caseating granuloma in tuberculosis.

Laboratory Tests

An ultrasound of the neck was ordered, and it showed a hypoechoic lesion with cystic component in the right submandibular region measuring 1.36 cm x 4.42 cm, suggesting an enlarged lymph node. The thyroid was normal. However, a CT scan was suggested for better evaluation.

The general surgery team was consulted, and they recommended for infectious disease evaluation and biopsy of the lesion. An HIV, hepatitis, and rapid plasma reagin panel were all negative. CBC, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and urinalysis were normal. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) showed a mixed population of lymphocytes with clusters of histiocytes; the giant cells were suggestive of granulomatous inflammation. FNA was negative for malignancy. The pathologist could not rule out TB with this FNA, so an excisional biopsy of the lymph node was advised.

In the meantime, the patient developed upper respiratory symptoms including sore throat, nasal congestion, sputum production, and mild cough, but no hemoptysis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was found to be elevated at 52 mm/hr. She was prescribed cefuroxime. Sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smears and culture were sent, all of which came back negative.

Surgery

The patient was scheduled for lymph node excision surgery. The surgeon found matted lymph nodes along with a collection of purulent materials that were questionable for a cold abscess. The pathology report noted potential epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells with small central areas of necrosis, granulation tissue, and fibrosis; the occasional AFB cell was identified, but there was no evidence of malignancy. During this time, the patient was about 35 weeks into her pregnancy, and the pulmonary and infectious disease teams agreed to start the patient on anti-TB therapy—isoniazid 300 mg/d, rifampin 600 mg/d, ethambutol 1200 mg/d, and pyridoxine 40 mg/d.

In mid-July, the patient had a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. Post-delivery, she was confirmed as having TB. A chest x-ray showed clear lungs, no extensive lymphadenopathy, and no cavitary granulomatous lesions. No purified protein derivative test was done, and the patient was asked to continue her anti-TB treatment for 9 months duration.

The patient missed about 6 months of her rifampin treatment, but otherwise continued to do well and finished the anti-TB therapy in late February the following year.

Seven months later, she developed a productive cough, vomiting, decreased appetite, significant weight loss (15 kg), pedal edema, and elevated blood sugars. Her hemoglobin A1c was elevated at 7.5%, and the patient was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. She was started on metformin and given multiple antibiotics.

Ophthalmology Clinic

In late September, during follow up in the internal medicine clinic, the patient was found to have redness in her eyes. She complained of blurry vision, photophobia, and pain in both eyes. The patient was referred to ophthalmology.

The slit lamp exam showed keratoconjunctivitis, sicca (not specified as Sjögren syndrome) and bilateral anterior uveitis. No evidence of diabetic retinopathy. The patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids and antibiotic eye drops, but that did alleviate her pain. She was seen another 4 times in the ophthalmology clinic the following month due to her worsening course and development of choroiditis patches in the periphery.

Bilateral granulomatous uveitis—and now choroiditis, probably of TB etiology—was suspected. Topical corticosteroid potency was increased, atropine was added, and systemic corticosteroids were considered; since immunosuppression can reactivate TB, this option was not taken. The patient was restarted on anti-TB therapy. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), and other labs were sent. The patient was referred to a specialized uveitis center in Kerala, India.

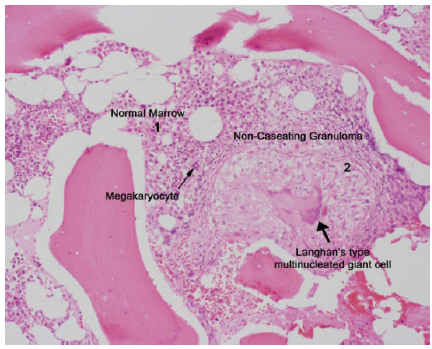

Figure 2. Noncaseating granuloma in sarcoidosis.

Specialized Uveitis Center

The patient developed diffuse joint pains and had some intermittent swelling in the ankles. She also complained of fatigue, weight loss, dry eyes, dry mouth, and had swelling of both parotids. She reported no rashes, photosensitivity, or oral ulcers. Cranial nerves exam was normal.

Until now, the sputum cultures, 3 AFB smears, and cultures were all negative, although the CBC was remarkable for elevated platelets at 506 × 109/L. A comprehensive metabolic panel was remarkable for elevated calcium at 2.73 mmol/L. ESR was elevated at 35 mm/hr and C-reactive protein levels were recorded at 25 mg/L.

Rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibody, and ANCA levels were negative. Complement C3 and C4 normal. Vitamin D was low at 23.8 ng/mL. Iron studies were remarkable for low iron at 3.2, low transferrin at 19.5, and elevated ferritin at 364 ng/mL. Quantiferon gold test was negative. The patient had already been treated with 1.5 anti-TB drug cycles, but continued to lose her vision.

Figure 3. Granulomatous uveitis.

Diagnosis

The causes of uveitis include connective tissue diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematous, Behcet’s disease), spondyloarthropathies (eg, ankylosing spondylitis), inflammatory bowel disease (eg, Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis), sarcoidosis infections (eg, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, herpes, TB, West Nile virus), cancers (eg, lymphoma), trauma, or an idiopathic etiology of uveitis.1,2 In this case, the patient presented with granulomatous uveitis. Ophthalmic characteristics of granulomatous uveitis include keratitic precipitating over the endothelium (in granulomatous pathologies, these are large) and mutton fat nodules that are visible over the corneal endothelium.3,4 Busacca nodules are present over surface of iris, while Koeppe nodules located at pupillary border.5

A chest CT is more sensitive than a chest x-ray for detecting hilar lymphadenopathy and, in this case, it confirmed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and an increased number of small mediastinal and axillary lymph nodes.3 The CT also showed patchy diffuse distributed areas with ground glass opacity, interlobular, nodular, and irregular septal thickening, mild central bronchiectasis, and small areas with fibrotic interstitial changes in both recesses.

ACE came back elevated at 221 U/L (normal: 12-68 U/L). Serum protein electrophoresis and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 were both normal. Extractable ANA panel, HLA-B27, and anticyclic citrullinated peptides (prior RF) were negative, and the EKGs were unremarkable.

We referred the patient back to the pulmonary team for a bronchoscopy. Endobronchial and transbronchial biopsy showed non-necrotizing granulomas and foreign body type multinucleate giant cells; the Zeihl-Neelsen stain was negative for AFB. The pathology report confirmed that the nuclear morphological type of granuloma with sarcoidal.

Treatment

The patient was started on high-dose corticosteroids and has responded very well.6.7 Her vision improved tremendously and her other symptoms have mostly resolved.

This case highlights the importance of making the right diagnosis. The patient had been treated for TB, but her uveitis was getting worse. Questioning the initial diagnosis and reassessing the work-up, pathology slides, and ophthalmic findings were necessary to best treat the patient.

Acknowledgements

The pathology slide was provided by Dr. Deepa Dutta from the pathology department at The Sinai Hospital of Baltimore. Some of the material was presented as a poster at the Endocrine Society meeting in San Diego in June 2010.

Samer Nuhaily, MD, is a consultant rheumatologist and chief of service at Universal Hospital, in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Babar Navid, MD, is a consultant pulmonologist at Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Ramzi Ghanem, MD, is a consultant ophthalmologist at Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Rani Jacob, MD, is a specialist ophthalmologist at Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Zujajah Hassan, MD, is a consultant internist at Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Mustafa Al Maini, MD, is a consutant rheumatologist at Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Shabeer Nellikode, MD, is a neurologist and managing director at Universal Hospital in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Asim Abbasi, MD, MPH, is an attending physician at Excel Care in Houston, TX.

References:

1.Szepessy Z. Uveitis in sarcoidosis. Orv Hetil. 2013;154(45):1798-1801.

2.Pan J, Kapur M, McCallum R. Noninfectious immune-mediated uveitis and ocular inflammation. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(1):409.

3.Caspers LE, Ebraert H, Makhoul D, et al. Broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) for the diagnosis of sarcoidosic uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(2):102-109.

4. Sungur G, Hazirolan D, Bilgin G. Pattern of ocular findings in patients with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis in Turkey. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(6):455-461.

5.Fieß A, Frisch I, Halstenberg S, Steinhorst U. Three cases—one diagnosis: ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2013;230(5):530-535.

6.Jamilloux Y, Bonnefoy M, Valeyre D, et al. Elderly-onset sarcoidosis: prevalence, clinical course, and treatment. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(12):969-978.

7. Sánchez-Cano D, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Ríos-Fernández R, Ortego-Centeno N. Off-label uses of anti-TNF therapy in three frequent disorders: Behçet's disease, sarcoidosis, and noninfectious uveitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:286857.