Peer Reviewed

Gastric Volvulus

A 5-week-old breastfed boy presented to the pediatric gastroenterology office for evaluation of possible gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). He was born full-term via Cesarean delivery with a birth weight of 3376 g. At 9 days of life, he started having painful burps, as well as nonbloody, nonbilious spit up after breastfeeding. With each attempt at feeding, he cried, arched his back, and stiffened his body. At 9 days of life, the boy weighed 3283 g, which was approximately 3% below his birth weight. Due to the ongoing symptoms associated with episodes of spitting up, his pediatrician started him on 4 mg/kg/day of ranitidine at 4 weeks of life.

On physical examination in the gastroenterology office, the boy was awake, alert, and in no acute distress. The results of his abdominal examination were unremarkable, and he did not have any abdominal distension, tenderness on palpation, palpable abdominal masses, or hepatosplenomegaly. The ranitidine was maximized for his weight. Given concern for a possible cow’s milk protein allergy contributing to his symptoms of spitting up, pain with feeds, and initial slow weight gain, the boy was transitioned from breast milk to an extensively hydrolyzed formula.

The boy was seen weekly by his pediatrician for weight checks. At 8 weeks of life, he returned to the gastroenterology office with persisting symptoms, and he was transitioned from ranitidine to lansoprazole. Follow up at 11 weeks of life revealed continued spitting up and worsening failure to thrive with a weight of 4550 g (1.2% of weight for age). He was transitioned to an elemental formula with increased caloric density per ounce of formula. Given his ongoing spit up and poor weight gain, laboratory testing and imaging were performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a transaminitis with alanine aminotransferase of 83 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase of 66 U/L, for which infectious and metabolic evaluations were performed and were negative. Abdominal ultrasonography results were unremarkable. An upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series revealed a horizontally-oriented stomach with inversion of the greater and lesser curvatures, as well as inferiorly-oriented vertical course of the distal stomach suggestive of organoaxial gastric volvulus (Figure 1).

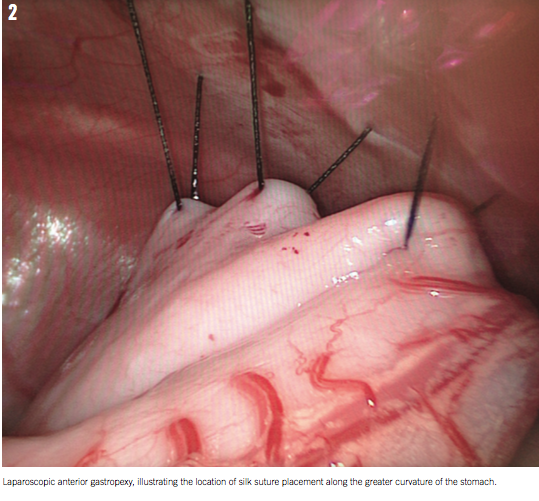

The boy was taken to the operating room, where he underwent laparoscopic gastric detorsion and gastropexy to the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 2). He had an unremarkable postoperative course and was discharged home on postoperative day 4. At follow up, he had improvement in his symptoms, and his oral intake returned to normal with improved weight gain. The transaminitis subsequently resolved.

DISCUSSION

Gastric volvulus presents in both acute and chronic forms. Although gastric volvulus is a rare condition,1-4 the diagnosis should be considered in pediatric patients in the appropriate clinical setting. Presenting symptoms are nonspecific and resemble those of more common pediatric diagnoses, and delay in diagnosis has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1,5

The stomach is normally fixed in the abdominal cavity by 4 ligaments: gastrocolic, gastrohepatic, gastrophrenic, and gastrosplenic. Abnormalities including agenesis, elongation, or disruption of any of these 4 ligaments can predispose patients to the development of primary gastric volvulus. Secondary gastric volvulus can result from gastric, splenic, or diaphragmatic abnormalities that predispose an individual to volvulus. The most common anomalies predisposing to secondary gastric volvulus include diaphragmatic eventration, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, paraesophageal hernia, intestinal malrotation, wandering spleen, asplenism, and hiatal hernia. It is estimated that 69% of cases of acute gastric volvulus have an associated pathologic abnormality.1

Gastric volvulus can be acute or chronic, with some cases presenting as acute gastric volvulus with history suggestive of chronic gastric volvulus. Acute gastric volvulus can be life-threatening and requires a heightened suspicion for diagnosis.5 Common presenting symptoms include nonbilious emesis, abdominal distension, retching, and pain. Delay in intervention can lead to strangulation, gastric ischemia, and necrosis, which can result in significant morbidity and mortality. Patients with chronic gastric volvulus are more likely to present with feeding difficulties, growth failure, recurrent emesis, respiratory infections, and/or abdominal distension.1,6 The symptoms common to gastric volvulus are similar to the symptoms associated with many other pediatric diagnoses such as GERD and cow’s milk protein allergy. These similarities may lead to delayed diagnosis.

Three types of gastric volvulus are described in the literature: organoaxial, mesenteroaxial, and combined type. The type of volvulus is classified by the axis upon which the stomach rotates. In organoaxial volvulus, the stomach rotates on a longitudinal axis and is more likely to present in a chronic manner. In mesenteroaxial volvulus, the stomach rotates on an axis perpendicular to its longitudinal axis and is more likely to present acutely with greater associated morbidity and mortality.1,5

When the diagnosis of gastric volvulus is suspected, patients should undergo prompt evaluation with a UGI series to evaluate the position of the stomach. In organoaxial volvulus, the stomach may appear to be “upside-down” and lies in a horizontal orientation. In mesenteroaxial volvulus, the stomach lies in a vertical plane and the pylorus and antrum may be found superior to the gastroesophageal junction.1,7

Once diagnosed, initial steps in management of gastric volvulus include hemodynamic stabilization when necessary, and gastric decompression followed by surgery,7,8 either via laparotomy or laparoscopy. Surgical intervention is the preferred treatment for both acute and chronic gastric volvulus in North America. Surgical management consists of gastric detorsion, resection, and repair of areas of perforation, as well as gastric fixation. Fixation can be performed by anterior gastropexy, fundic gastropexy, or via gastrostomy tube placement.6

The risk of recurrent gastric volvulus is increased if coexisting defects go unrepaired.1 Thus, when there are associated diaphragmatic abnormalities, they should be repaired at the time of surgery. Consideration can also be given to attempting medical management in cases of chronic gastric volvulus. Medical management is more commonly used outside of the United States. Nonoperative management includes infant positioning right-side down or prone with the head elevated above the torso after feeding. This position may facilitate keeping the dependent portion of the stomach inferior to the lesser curvature, which may decrease the risk of volvulus.1

The prognosis of gastric volvulus depends on the type and whether surgical intervention is delayed. More than two-thirds of deaths associated with both acute and chronic gastric volvulus are attributed to delays in diagnosis and surgical intervention.1 In a study of 581 patients by Cribbs and colleagues, 23% of patients with acute gastric volvulus presented with an acute, life-threatening event that required lifesaving resuscitative measures. The mortality rate in patients presenting with acute gastric volvulus was 6.7%. The mortality rate in patients requiring resuscitation at presentation was 6.9%, and the overall operative mortality rate was 5.3%. It was determined that 12 of 17 deaths may have been prevented with more timely and effective surgical intervention. In patients with chronic gastric volvulus, the overall mortality rate was found to be 2.7%.1

CONCLUSION

The morbidity and mortality associated with both acute and chronic gastric volvulus necessitates the need for heightened suspicion and prompt management of the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting. In our patient, who did not respond to initial acid suppression with ranitidine and elemental formula, imaging could have been considered earlier before introducing lansoprazole and thickening formula. This may have led to earlier diagnosis and allowed for surgical intervention.

This case illustrates the importance of considering alternative diagnoses such as pyloric stenosis and hiatal hernia, as well as less common diagnoses such as gastric volvulus, when a patient fails to respond to conventional management for more commonly encountered conditions.

Lesley Small-Harary, MD, is a clinical fellow in the Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

Demetri J. Merianos, MD, is an assistant professor of surgery in the Division of Pediatric Surgery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

Elaine Barfield, MD, is an assistant professor of pediatrics in the Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

REFERENCES

1. Cribbs RK, Gow KW, Wulkan ML. Gastric volvulus in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):752-762.

2. Gourgiotis S, Vougas V, Germanos S, Baratsis S. Acute gastric volvulus: diagnosis and management over 10 years. Dig Surg. 2006;23(3):169-172.

3. Basaran UN, Inan M, Ayhan S, et al. Acute gastric volvulus due to deficiency of the gastrocolic ligament in a newborn. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(5):288-290.

4. Duman L, Savas MC, Büyükyavuz BI, Akcam M, Sandal G, Aktas AR. Early diagnostic clues in neonatal chronic gastric volvulus. Jpn J Radiol. 2013;31(6):401-404.

5. Oh SK, Han BK, Levin TL, Murphy R, Blitman NM, Ramos C. Gastric volvulus in children: the twists and turns of an unusual entity. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(3):297-304.

6. Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011.

7. Garel C, Blouet M, Belloy F, Petit T, Pelage JP. Diagnosis of pediatric gastric, small-bowel and colonic volvulus. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(1):130-138.

8. Miller DL, Pasquale MD, Seneca RP, Hodin E. Gastric volvulus in the pediatric population. Arch Surg. 1991;126(9):1146-1149.

1. Godshall D, Mossallam U, Rosenbaum R. Gastric volvulus: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:837-840.

2. Cozart JC, Clouse RE. Gastric volvulus as a cause of intermittent dysphasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43; 1057-1060.

3. Green J, Stein, M. Gastric volvulus. EMedicine. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/radio/topic296.htm. Accessed August 15, 2007.