Infants and toddlers will put just about anything into their mouths. Each year in this country, between 100,000 and 200,000 incidents of foreign-body ingestions are reported to poison control centers.1,2 The large majority of ingestions are accidental. (In adolescents, ingestions are usually intentional.) The most commonly ingested objects are coins, toy parts, sharp objects, and batteries. Management depends on the object that has been ingested, its location, and the patient's age and size. ---- John Harrington, MD New York Medical College |

Coin Ingestion

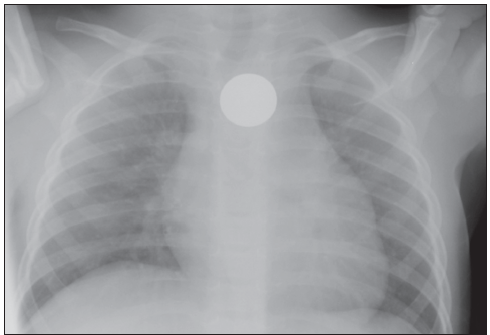

These radiographs show a penny lodged in the upper to mid esophagus of a 13-month-old. Because the coin triggered drooling and pain, its removal was required.

When a foreign body is lodged in a patient's esophagus, prompt evaluation is indicated. Respiratory symptoms, esophageal erosions, and (rarely) esophageal-aortic fistulas with exsanguinations and death may be among the consequences.

Swallowed coins are usually found in the proximal esophagus at the region of the thoracic inlet; the middle esophagus, at the region of the carina; or the distal esophagus, proximal to the gastroesophageal junction.

Studies suggest that if an esophageal coin causes no symptoms, the patient may be observed for up to 16 hours1,2:

•If the ingestion occurred within the previous 24 hours.

•If there are no underlying esophageal or tracheal abnormalities.

Approximately 25% to 30% of coins pass into the stomach--particularly in older children and in those with a coin in the distal esophagus.

Endoscopic removal under general anesthesia with Magill forceps is the common treatment of choice when a coin remains lodged in the esophagus longer than 24 hours.

REFERENCES

1. Soprano JV, Fleisher GR, Mandl KD. The spontaneous passage of esophageal coins in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1073-1076.

2. Waltzman ML, Baskin M, Wypij D, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:614-619.

(Case and radiographs courtesy of John Harrington, MD, of New York Medical College and Maria Fareri Children's Hospital in Valhalla, NY.)

A 14-year-old boy was brought to the emergency department after he had swallowed a pushpin. He had been chewing on the pin when the family cat startled him. Initially, he gasped and started choking and coughing. Thereafter, he complained of intermittent cough; he had no respiratory distress or stridor.

His medical history was significant for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Immunizations were up-to-date, and he had no drug allergies.

The patient was alert, cooperative, and in no acute distress. Heart rate was 88 beats per minute; respiration rate, 16 breaths per minute; blood pressure, 107/72 mm Hg; and pulse oximetry, 98% on room air. Mild, bilateral expiratory wheezes were heard on chest auscultation; no chest wall retractions were noted. The remaining physical examination findings were normal.

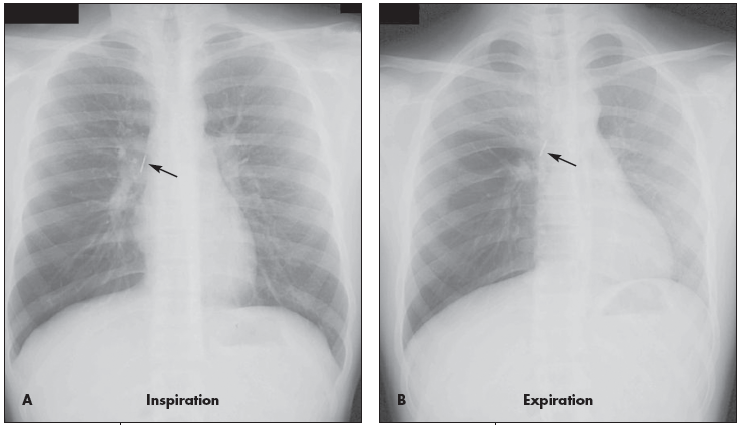

Inspiratory (A), expiratory (B), and lateral (C) chest radiographs confirmed the diagnosis of an endobronchial foreign body. Bronchoscopy revealed a blue pushpin obstructing the right bronchus intermedius and facing proximally into the large airways (D). The larynx, trachea, carina, and left main bronchus were not affected.

The pin was grasped with optical peanut-grabber forceps, it was dropped in the oropharynx and retrieved with McGill forceps and then removed with the bronchoscope. Repeated bronchoscopy showed a completely normal airway without scratches, abrasions, or punctures. The patient recovered well and was discharged later that day.

The innate tendency of young children to explore with the mouth, their narrow airways, and immature protective mechanisms place youngsters at relatively high risk for foreign-body aspiration.1 The  incidence is high in toddlers, especially those between 24 and 36 months of age.2 Signs of airway obstruction (eg, choking, coughing, stridor) and respiratory distress/arrest may be apparent on presentation. One study showed that only 15.7% of patients presented with the clinical triad of concomitant cough, localized wheezing, and decreased breath sounds; a high positive predictive value with poor sensitivity was noted in all clinical findings.2 Symptoms may resolve despite the presence of a foreign body, depending on its size, chemical composition, and location in the tracheobronchial tree.3 The absence of respiratory distress does not rule out an endobronchial foreign body.

incidence is high in toddlers, especially those between 24 and 36 months of age.2 Signs of airway obstruction (eg, choking, coughing, stridor) and respiratory distress/arrest may be apparent on presentation. One study showed that only 15.7% of patients presented with the clinical triad of concomitant cough, localized wheezing, and decreased breath sounds; a high positive predictive value with poor sensitivity was noted in all clinical findings.2 Symptoms may resolve despite the presence of a foreign body, depending on its size, chemical composition, and location in the tracheobronchial tree.3 The absence of respiratory distress does not rule out an endobronchial foreign body.

Chest radiographs may demonstrate air trapping, atelectasis, or consolidation and are suggestive of a radiopaque foreign body.4 In older children like this patient, chest radiographs should be obtained during inspiration and expiration. Fluoroscopy may be needed in young children. In a 10-year retrospective study, plain chest radiographs revealed a foreign body in only 23.56% of patients.5 In another retrospective study, chest radiographs were normal in 56% of children with tracheal foreign bodies.6

A reliable history dictates the need for bronchoscopy, even when symptoms are minimal and radiographic findings are inconclusive. A rigid bronchoscope with or without grasping forceps can be used.5 Complications include airway injury, barotrauma (pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum), laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, infection, and cardiopulmonary arrest.2,5,6 The most commonly retrieved non- radiopaque foreign bodies are peanuts, carrots, apple slices, popcorn, beads, pearls, pegs, and small toys. The most common radiopaque foreign bodies are pins.5 Aspirated foreign bodies are found in both the right and left bronchial tree, despite the anatomic predilection for the right side.5

A reliable history dictates the need for bronchoscopy, even when symptoms are minimal and radiographic findings are inconclusive. A rigid bronchoscope with or without grasping forceps can be used.5 Complications include airway injury, barotrauma (pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum), laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, infection, and cardiopulmonary arrest.2,5,6 The most commonly retrieved non- radiopaque foreign bodies are peanuts, carrots, apple slices, popcorn, beads, pearls, pegs, and small toys. The most common radiopaque foreign bodies are pins.5 Aspirated foreign bodies are found in both the right and left bronchial tree, despite the anatomic predilection for the right side.5

When a young child presents with acute respiratory symptoms, consider an aspirated foreign body in the differential diagnosis and maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion.

REFERENCES:

1. Johnson DG, Condon VR. Foreign bodies in the pediatric patient. Curr Probl Surg. 1998;35:271-379.

2. Midulla F, Guidi R, Barbato A, et al. Foreign body aspiration in children. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:663-668.

3. Tokar B, Ozkan R, Ilhan H. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children: importance of accurate history and plain chest radiography in delayed presentation. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:609-615.

4. Swischuk LE. Chapter 1: Chest. In: Emergency Radiology of the Acutely Ill or Injured Child. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

5. Sersar SI, Rizk WH, Bilal M, et al. Inhaled foreign bodies: presentation, management and value of history and plain chest radiography in delayed presentation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:92-99.

6. Ciftci AO, Bingol-Kologlu M, Senocak ME, et al. Bronchoscopy for evaluation of foreign body aspiration in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1170-1176.

(Case and photographs courtesy of Manu Madhok, MD, MPH, and Jose M. Jimenez-Vega, BHS, of Children's Hospitals of Minnesota in Minneapolis.)

Figures A, B, and C track the course of a 1½-inch tack traversing the GI tract of a 2-year-old. With the exception of straight pins, sharp foreign bodies increase the complication rate associated with ingestions from less than 1% to about 25%. Straight pins usually follow a benign course, unless multiple pins have been ingested.

Figures A, B, and C track the course of a 1½-inch tack traversing the GI tract of a 2-year-old. With the exception of straight pins, sharp foreign bodies increase the complication rate associated with ingestions from less than 1% to about 25%. Straight pins usually follow a benign course, unless multiple pins have been ingested.

In this patient's case, serial abdominal radiographs followed the tack along a predictable path. It was expelled with no complications within 24 hours.

(Case and radiographs courtesy of John Harrington, MD, of New York Medical College and Maria Fareri Children's Hospital in Valhalla, NY.)