Fatal Pulmonary Toxicity After a Short Course of Amiodarone Therapy

Key words: Amiodarone, antiarrhythmic medications, corticosteroids, pulmonary toxicity.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Amiodarone, a commonly used antiarrhythmic medication, is the treatment of choice for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and for preventing the recurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmias. Although amiodarone has many potential adverse effects, these typically develop in the setting of long-term treatment. Acute pulmonary toxicity (APT) is of particular concern and correlates with total cumulative dose; toxicity is unlikely with short-duration amiodarone treatment.

Two mechanisms are thought to be involved in the development of APT related to amiodarone therapy: direct cytotoxicity and hypersensitivity reactions. APT is more common in men, older persons, and patients with lung disease.1,2 It has been suggested that race may increase susceptibility to pulmonary toxicity, with one report showing a higher prevalence among individuals of Japanese descent.3 Finally, exposure to supplemental oxygen, alone or combined with mechanical ventilation, may also potentiate APT in the setting of amiodarone therapy.

We report the case of a patient who developed severe pulmonary toxicity leading to death after only 50 days of low-dose amiodarone therapy, despite withdrawal of amiodarone and the administration of corticosteroids. This case adds to the literature demonstrating that acute APT can develop even with low doses and short courses of amiodarone therapy. Physicians should evaluate the risk-to-benefit ratio of amiodarone treatment and be vigilant even when prescribing low doses, especially in patients at higher risk of developing this complication.

Case Report

An 87-year-old Vietnamese man who was in good health except for hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia underwent elective aortic valve replacement because of severe aortic stenosis. The patient had never smoked and had no known underlying lung disease or allergies. Four days later, he developed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate of 160 beats per minute. Two 150-mg intravenous bolus doses of amiodarone resulted in conversion to sinus rhythm. Oral amiodarone therapy was started, and the patient was discharged to home with a prescription for amiodarone 200 mg once daily to be taken for a total duration of 3 months. Before discharge, a routine postoperative chest radiograph showed small bilateral effusions in the lungs.

On day 49 of amiodarone therapy, the patient was readmitted to the hospital because of severe acute dyspnea with occasional bloody sputum. On physical examination, he was afebrile but tachypneic, with an oxygen saturation of 91% while breathing room air. Arterial blood gas measurements showed respiratory alkalosis and severe hypoxemia, with a pH of 7.52 (normal, 7.35-7.45), a Po2 of 40 mm Hg (normal, 73-103 mm Hg), a Pco2 of 26 mm Hg (35-45 mm Hg), and an HCO3 of 23.6 mEq/L (normal, 22-26 mEq/L). The complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. He had a C-reactive protein of 97 mg/L (normal, <10 mg/L) and an NT-proBNP of 2093 ng/L (normal, <738 ng/L).

A repeated chest radiograph now revealed diffuse bilateral infiltrates in the lungs (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan was undertaken and showed thickened alveolar septa and ground glass opacities in both lungs, which were most apparent in the upper lobes (Figure 2). Blood and sputum cultures were obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated to treat a potential underlying pulmonary infection. Amiodarone was discontinued at the same time.

A repeated chest radiograph now revealed diffuse bilateral infiltrates in the lungs (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan was undertaken and showed thickened alveolar septa and ground glass opacities in both lungs, which were most apparent in the upper lobes (Figure 2). Blood and sputum cultures were obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated to treat a potential underlying pulmonary infection. Amiodarone was discontinued at the same time.

Despite antibiotic treatment, the patient’s severe hypoxemia persisted. Noninvasive ventilation was initiated, but the patient refused orotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation. A transthoracic echocardiography was performed and showed normal functioning of the left ventricle and of the prosthetic aortic valve. The function of the right ventricle was normal as well, and the systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 45 mm Hg. Results of blood and sputum cultures were negative for bacteria and for mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage were performed, which showed an increased percentage of lymphocytes (64%) and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (30%). The cultures of both the bronchoalveolar lavage and the bronchial washings were negative. Prednisone 1 mg/kg (40 mg) daily was started. The patient’s clinical condition continued to worsen despite corticosteroid therapy, and palliative care was initiated. The outcome was rapidly fatal.

Discussion

This case documents a death related to severe pulmonary toxicity after a short course of low-dose amiodarone treatment, at a cumulative dose of 10 g in less than 2 months. Although APT usually occurs after many months of treatment with high cumulative doses, several other case reports have also demonstrated that APT can happen at any time, even with low-dose amiodarone therapy.3-8

The incidence of amiodarone-induced APT ranges between 5% and 13%, and mortality rates from APT range from 10% to 23%.9 Risk factors for the development of APT from amiodarone therapy include a high cumulative dose (101-150 g), a daily dose >400 mg, duration of therapy exceeding 2 months, older age, and underlying lung disease. In a report by Ernawati and colleagues,1 only the patient’s age (>60 years) and the duration of therapy significantly affected the risk of APT.

Several pulmonary disorders may occur in patients treated with amiodarone: chronic interstitial pneumonitis (the most common form), organizing pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and, atypically, development of a solitary pulmonary fibrotic mass. Patients with these disorders usually have a nonproductive cough and dyspnea, with some patients also having a fever on presentation.

One factor that may have contributed to APT in our patient was his recent aortic valve replacement surgery. ARDS has been reported in patients treated with amiodarone who have undergone surgery.5,8,10 It has been hypothesized that amiodarone may sensitize patients to high concentrations of inspired oxygen fraction, which could explain the development of ARDS following cardiac or pulmonary surgery. However, it is precisely for these conditions that amiodarone is largely used and necessary.

The Vietnamese ethnicity of our patient may have played a role in his development of APT. Yamada and colleagues3 showed a relatively high incidence of pulmonary toxicity in Japanese patients in the setting of low-dose amiodarone therapy. This finding suggests that race might influence drug side effects, with a potential association between genetic factors and APT. More research in this area might be warranted to determine which races may be most susceptible to amiodarone-induced APT.

Diagnosis

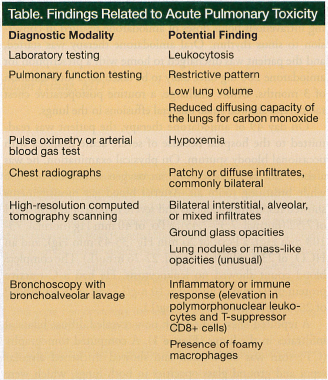

In the absence of a lung biopsy, which is the only diagnostic modality that provides a definitive diagnosis, APT is diagnosed based on the patient’s symptoms, clinical examination, chest radiographs, pulmonary function tests, high-resolution CT scanning, and bronchoalveolar lavage (Table).

In the absence of a lung biopsy, which is the only diagnostic modality that provides a definitive diagnosis, APT is diagnosed based on the patient’s symptoms, clinical examination, chest radiographs, pulmonary function tests, high-resolution CT scanning, and bronchoalveolar lavage (Table).

Treatment

The treatment of amiodarone-induced APT consists of discontinuing amiodarone therapy. Corticosteroids (prednisolone 0.75-1.0 mg/kg daily) should be given when hypoxemia is present or extensive involvement of the lungs is apparent on imaging, as these agents may help accelerate recovery and minimize the likelihood of lung fibrosis. In addition, because amiodarone has a long half-life (around 50 days), it persists in the lungs and requires a prolonged course of corticosteroid therapy to avoid relapse. When clinical improvement and clearing of pulmonary opacities occur within a few months after discontinuing the drug, the prognosis is usually favorable; however, if pulmonary fibrosis is present or develops or if ARDS develops, the mortality rate is substantial.

Before amiodarone is started, the patient must undergo pulmonary evaluation with chest radiographs and pulmonary function testing, including assessment of the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, to provide baseline lung function information. Early detection of APT may improve the prognosis, so patients should be encouraged to report pulmonary symptoms, and clinical follow-up every 3 to 6 months is necessary. Repeated chest radiographs and lung function tests are indicated if the patient develops new symptoms.11

Conclusion

Whenever possible, low-dose amiodarone should be used as briefly as possible because there are no adequate predictors of pulmonary toxicity with this agent’s use. Amiodarone should not be used in patients with significant pulmonary disease. An alternative antiarrhythmic drug, such as a beta-blocking agent or calcium channel blocker, should be used instead. Close clinical follow-up to detect early signs of pulmonary involvement is strongly recommended.

References

1. Ernawati DK, Stafford L, Hughes JD. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):82-87.

2. Camus P, Martin WJ 2nd, Rosenow EC 3rd. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25(1):65-75.

3. Yamada Y, Shiga T, Matsuda N, Hagiwara N, Kasanuki H. Incidence and predictors of pulmonary toxicity in Japanese patients receiving low-dose amiodarone. Circ J. 2007;71(10):1610-1616.

4. Pourafkari L, Yaghoubi A, Ghaffari S. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(5):465-466.

5. Kaushik S, Hussain A, Clarke P, Lazar HL. Acute pulmonary toxicity after low-dose amiodarone therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(5):1760-1761.

6. Ott MC, Khoor A, Leventhal JP, Paterick TE, Burger CD. Pulmonary toxicity in patients receiving low-dose amiodarone. Chest. 2003;123(2):646-651.

7. Kharabsheh S, Abendroth CS, Kozak M. Fatal pulmonary toxicity occurring within two weeks of initiation of amiodarone. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(7):896-898.

8. Ashrafian H, Davey P. Is amiodarone an underrecognized cause of acute respiratory failure in the ICU? Chest. 2001;120(1):275-282.

9. Oyama N, Oyama N, Yokoshiki H, et al. Detection of amiodarone induced pulmonary toxicity in supine and prone positions. High-resolution computed tomography study. Circ J. 2005;69(4):466-470.

10. Van Mieghem W, Coolen L, Malysse I, Lacquet LM, Deneffe GJ, Demedts MG. Amiodarone and the development of ARDS after lung surgery. Chest. 1994; 105(6):1642-1645.

11. Schwaiblmair M, Berghaus T, Haeckel T, Wagner T, von Scheidt W. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity: an under-recognized and severe adverse effect? Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99(11):693-700.

Disclosures:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Magali-Noëlle Pfeil, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois

Rue du Bugnon 21

CH-1011 Lausanne, Vaud, Switzerland