Eosinophilic Esophagitis: An Increasingly Common Condition Among Children

Authors:

Patrice G. Kruszewski, DO, and Elizabeth A. Erwin, MD

ABSTRACT: Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is becoming more common among the US pediatric population. The chronic condition is related to food antigen exposure in the esophagus. The diagnosis is based on symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and increased numbers of eosinophils in the esophagus after other etiologies of esophageal eosinophilia have been ruled out. Treatment includes topical corticosteroids, dietary modifications, or an exclusive elimination diet. Esophageal dilation is needed in cases of esophageal strictures. Complications include esophageal narrowing and strictures related to inflammation and fibrosis. Possible treatment complications include nutritional deficiencies, adrenal suppression, and corticosteroid-related esophageal candidiasis. A multidisciplinary approach to treatment that includes a pediatric gastroenterologist, an allergist, and a nutritionist can help patients and families manage EoE.

KEYWORDS: Eosinophilic esophagitis, pediatrics, dysphagia, food impaction, esophageal dilation, corticosteroids, elimination diet

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic allergic condition that is a result of immune-mediated inflammation of the esophagus. It is now generally accepted that EoE is directly related to food antigens.1 The diagnosis of pediatric EoE is increasing at an alarming rate. It is estimated that EoE affects approximately 4 of every 10,000 children in the United States.2 Recent epidemiologic data indicate that EoE is now a leading cause of dysphagia.2 The rise in incidence of EoE parallels the rise of other atopic diseases. EoE is now found to occur throughout the world.

EoE was first recognized as a distinct diagnosis in 1995 by Kelly and colleagues.3 They observed that 10 children who had severe symptoms similar to gastroesophageal reflux (GER)—vomiting, failure to thrive, and regurgitation—improved after treatment with an elemental formula. These patients were also noted to have elevated eosinophil counts on esophageal biopsies. After 6 weeks of taking an elemental formula, the symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia resolved in all of the children. This study provided the first evidence that foods are causal for EoE. Today it has become increasingly clear that EoE is a food antigen–driven condition.

PRESENTATION

Symptoms of EoE typically vary based on the age of the patient. Younger children tend to experience more difficulties with vomiting and poor weight gain, while adolescents more often present with dysphagia and food impactions. Other less common symptoms include chest pain, abdominal pain, and choking. Nevertheless, Noel and colleagues4 found that dysphagia and vomiting were the most common symptoms of EoE among pediatric patients.

In most cases of EoE, the symptoms are chronic and can last from childhood into adulthood. Analysis of a large pediatric EoE cohort5 found that the symptoms of more than 70% of patients who had pediatric EoE persisted into adulthood, including food impactions (40%), and many of these patients (14%) required therapeutic intervention with esophageal dilation. This study’s results suggest that pediatric EoE is a chronic condition that requires ongoing intervention and management.

There are a number of typical characteristics of patients with EoE. The majority of patients are male. Approximately 70% of patients with EoE also have at least one other concomitant atopic disease such as asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, or food allergies.1 There is also a genetic predisposition for EoE, as evidenced by the increased incidence of EoE in siblings and first-degree relatives.6

Diagnosis

The first clinical consensus guidelines for EoE were published in 2007 and were revised in 2011.1 In order to make the diagnosis of EoE, expert recommendations include the consideration of certain specific criteria, including symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and an increased number of esophageal eosinophils after exclusion of other etiologies of esophageal eosinophilia.

Other possible etiologies of esophageal eosinophilia include a vasculitic process, GER, inflammatory bowel disease, or a parasitic infection.7 GER can be difficult to exclude, given the fact that it is associated with esophageal eosinophilia and can exist concurrently with EoE. Although it does not completely exclude GER, treatment with a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) for at least 8 weeks has been recommended, either prior to endoscopy or as a first treatment after eosinophils have been found in the patient’s esophageal mucosa. Interestingly, some patients seem to experience resolution of eosinophilia with PPI treatment alone. This entity has been labeled PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia.

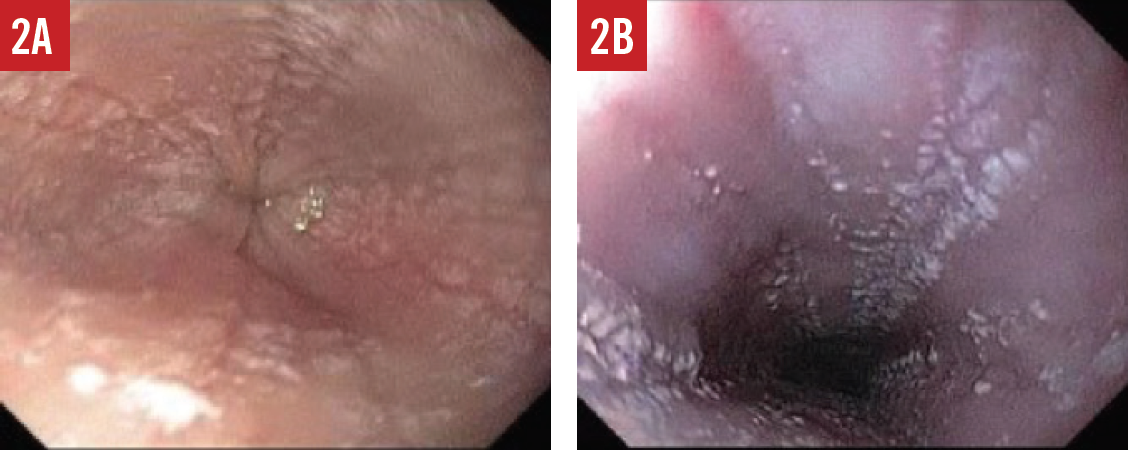

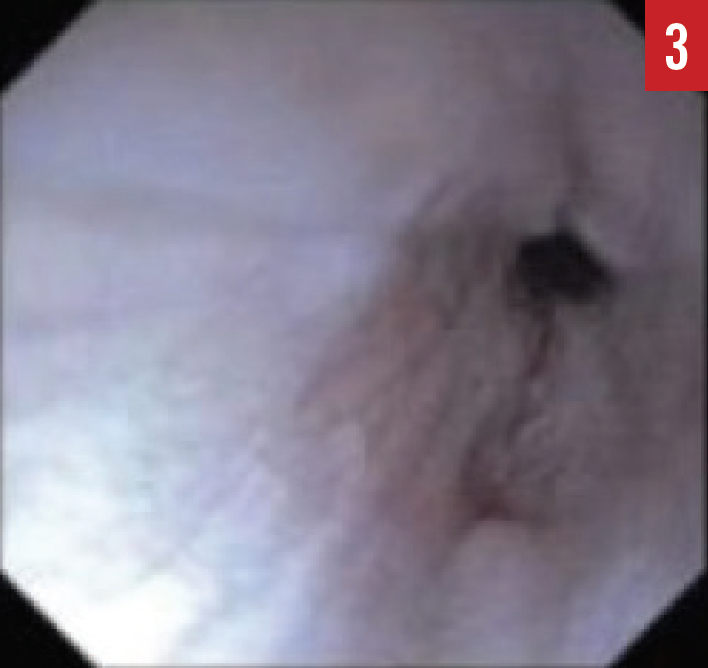

When the presence of EoE is suspected, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) must be performed by a pediatric gastroenterologist. During the EGD, biopsies are taken from various areas of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. A number of endoscopic features are common in patients with EoE, including esophageal edema, rings or strictures, esophageal furrowing, or white exudates (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1. An EGD image of a normal esophagus with smooth pink mucosa.

Figure 2. Endoscopic features of EoE include esophageal furrowing with lines directed downward (A) and exudates that are clusters of many eosinophils (B).

Figure 3. An EGD image of an esophageal stricture.

NEXT: Treatment, Referral, Complications

TREATMENT

Once a patient receives a diagnosis of EoE, the available treatment options should be discussed with the patient and family. Treatment for EoE consists of medications, dietary changes, and esophageal dilation.

The medications that are used to treat EoE are those used for asthma therapy, but they are administered differently for the treatment of EoE. Topical corticosteroids that have been studied for treatment of EoE include fluticasone and budesonide. Both have been shown to be effective in 50% to 90% of patients.8-10 Symptoms and histology typically improve with daily use of the medications. However, since EoE is chronic, patients tend to have relapse of their symptoms or histologic changes after the medications have been discontinued. It is difficult for children to continue daily medications on a chronic basis. There also are concerns about the chronic use of corticosteroids, including the risk of adrenal suppression, growth restriction, and esophageal candidiasis.1,11,12

Dietary therapy has also been proven to be effective therapy for EoE. It has also shown to be effective in reversing esophageal fibrosis in patients with EoE.13 The dietary treatments that have been studied include an elemental diet, specific food avoidance based on skin-prick testing (SPT) and patch testing, and empiric food elimination diets. An exclusive elemental diet is an amino-acid based formula, and it offers the best response of all therapies (medications and dietary modification). Approximately 96% of patients on an elemental diet have remission of EoE.14 A significant barrier to this therapy is that it is not palatable and therefore may be difficult to recommend without a gastrostomy tube. Furthermore, it may be difficult to maintain for an extended period and significantly alters the patient’s quality of life.

Elimination diets for EoE treatment have included allergy test–directed elimination or empiric elimination. Kagalwalla and colleagues treated pediatric EoE patients with the 6-food elimination diet (6FED) and found that 74% of patients had significant clinical and histologic improvement.15,16 The 6FED is based on the removal from the diet of foods containing the 6 most common food allergens: dairy, soy, egg, wheat, fish and shellfish, and peanuts and tree nuts. The 6FED is followed for 6 to 8 weeks, after which another endoscopy is done. Among the advantages of the 6FED is that it is not as restrictive as the elemental diet. However, it may not be nutritionally complete, and it may not identify the allergenic food. Also, multiple endoscopies are required—a patient undergoes endoscopy after each food has been reintroduced into the diet.

Another type of empiric diet that may be used focuses on the most common food allergens associated with EoE. Kagalwalla and colleagues found that cow’s milk (75%) and wheat (26%) were the most common food triggers of EoE.16 Studies investigating the removal only of cow’s milk from the diet have found that approximately 62% of patients who do so have resolution of EoE symptoms and mucosal changes.17,18 Empiric elimination of cow’s milk alone generally is a much easier diet for patients to follow, it does not require as many endoscopies, and it can be nutritionally complete. It also has its disadvantages, given the fact that cow’s milk may not be the sole allergen responsible for EoE and that it may not be the etiology of EoE for some patients.

Another dietary therapy that has been studied for EoE is a diet based on eliminating foods that are positive by allergy SPT or patch testing. The allergy SPT technique is based on having immunoglobulin E (IgE) bound to mast cells in the skin and is positive in patients with IgE-mediated allergies. Patch testing focuses on non-IgE–mediated reactions, which may be more relevant for EoE patients. Several studies in children and adults have reported the results of these tests and their use in planning treatment for EoE.19 Spergel and colleagues20 successfully treated 77% of their patients by removing cow’s milk as well as foods with positive results on SPT and patch testing. It is important to note that for the best outcomes using dietary treatment, cow’s milk must be removed regardless of the results of SPT or patch tests because of the low negative predictive value for milk testing (44%), even when both testing methods are used.21 Interestingly, a proportion of patients have negative SPT and atopy patch test results, and these patients may still improve with dietary restrictions.

REFERRAL

Dietary therapy is aimed at removal of the food allergens that trigger the development of EoE. As more foods are eliminated from their diet, patients may become deficient in micronutrients and macronutrients. Therefore, patients on dietary therapy for EoE may benefit from nutrition consultation in order to make sure they are receiving complete nutrition. A nutritionist can ensure that the patient is receiving adequate calories for growth and can help families prepare meals and adapt to the diet modification. Other challenges of dietary therapy include the expense and palatability. Some patients require a gastrostomy tube for formula administration. The quality of life of patients following dietary modification may be affected, as well.

Because EoE is an atopic disease, patients with it should also be managed by an allergist.1,22 The role of the allergist is to help manage the other atopic diseases such as asthma, food allergies, and eczema that occur frequently in patients with EoE. An allergist will be able to identify a patient’s potential aeroallergen and/or food triggers. Patients with EoE are increasingly managed in a multidisciplinary clinic by both a gastroenterologist and an allergist so that they can collaborate closely on the care of the patient.

Given the fact that many patients with EoE experience decreased quality of life, it may also be helpful to offer access to a pediatric psychologist.

COMPLICATIONS

Possible complications of EoE include esophageal fibrosis and the development of esophageal strictures. It is well documented that food impaction can occur in patients with EoE secondary to esophageal stenosis.5 As a consequence, patients with EoE may require medical intervention such as esophageal dilation and endoscopic removal of the food impaction. At this time, clinicians have not been able to identify which EoE patients will develop these severe manifestations of the condition. Research has shown that symptoms and histology correlate poorly.1,23 Therefore, there is concern that undertreatment of individuals who have ongoing inflammation may lead to these complications. Straumann and colleagues24 observed 30 untreated adult EoE patients for approximately 7 years; almost all continued to have dysphagia, and one-third required esophageal dilation.

Another possible complication of EoE is a lower health-related quality of life. A study completed by investigators at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center25 found that approximately 70% of EoE patients at their center had some type of psychological dysfunction. EoE patients may experience anxiety related to meals if they cannot follow the same diet as their peers; they may need to use gastrostomy feeding tubes if it is difficult for them to swallow. Other stressors that lead to anxiety or depression include frequent endoscopies, frequent physician office visits, and the need to use daily medication. In a study that compared oral fluticasone to cow’s milk elimination for the treatment of pediatric EoE,18 patients had a greater improvement in quality of life while following the cow’s milk elimination compared with fluticasone use. The quality of life of pediatric patients with EoE may be assessed using the validated PedsQL EoE Module.25

Patrice G. Kruszewski, DO, is a pediatric gastroenterologist in the Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Emory University/Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Georgia.

Elizabeth A. Erwin, MD, is a pediatric allergist/immunologist at the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

REFERENCES:

- Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3-20.e6.

- Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):589-596.e1.

- Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(5):1503-1512.

- Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):940-941.

- DeBrosse CW, Franciosi JP, King EC, et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):132-138.

- Spergel JM. New genetic links in eosinophilic esophagitis. Genome Med. 2010;2(9):60.

- Mehta P, Furuta GT. Eosinophils in gastrointestinal disorders: eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel diseases, and parasitic infections. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35(3):413-437.

- Aceves SS, Bastian JF, Newbury RO, Dohil R. Oral viscous budesonide: a potential new therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2271-2279.

- Faubion WA Jr, Perrault J, Burgart LJ, Zein NN, Clawson M, Freese DK. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with inhaled corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27(1):90-93.

- Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, Bastian J, Aceves S. Oval viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(2):418-429.

- Harel S, Hursh BE, Chan ES, Avinashi V, Panagiotopoulos C. Adrenal suppression in children treated with oral viscous budesonide for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(2):190-193.

- Golekoh MC, Hornung LN, Mukkada VA, Khoury JC, Putnam PE, Backelijauw PF. Adrenal insufficiency after chronic swallowed glucocorticoid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr. 2016;170:240-245.

- Lieberman JA, Morotti RA, Konstantinou GN, Yershov O, Chehade M. Dietary therapy can reverse esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a historical cohort. Allergy. 2012;67(10):1299-1307.

- Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(4):777-782.

- Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1097-1102.

- Kagalwalla AF, Shah A, Li BU, et al. Identification of specific foods responsible for inflammation in children with eosinophilic esophagitis successfully treated with empiric elimination diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(2):145-149.

- Kagalwalla AF, Amsden K, Shah A, et al. Cow’s milk elimination: a novel dietary approach to treat eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(6):711-716.

- Kruszewski PG, Russo JM, Franciosi JP, Varni JW, Platts-Mills TA, Erwin EA. Prospective, comparative effectiveness trial of cow’s milk elimination and swallowed fluticasone for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29(4):377-384.

- Wechsler JB, Schwartz S, Amsden K, Kagalwalla AF. Elimination diets in the management of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Asthma Allergy. 2014;7:85-94.

- Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):461-467.e5.

- Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Beausoleil JL, Shuker M, Liacouras CA. Predictive values for skin prick test and atopy patch test for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(2):509-511.

- Spergel JM. An allergist’s perspective to the evaluation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29(5):771-781.

- Aceves SS, Ackerman SJ. Relationships between eosinophilic inflammation, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(1):197-211.

- Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, Bucher KA, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(6):1660-1669.

- Franciosi JP, Hommel KA, Bendo CB, et al. PedsQL eosinophilic esophagitis module: feasibility, reliability, and validity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57(1):57-66.