Diagnosis and Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections: A Case-Based Mini-Review

Authors:

Eiyu Matsumoto, MB, and Jennifer R. Carlson, PA-C

Citation:

Matsumoto E, Carlson JR. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections: a case-based mini-review. Consultant. 2017;57(8):464-467.

ABSTRACT: Urinary tract infection (UTI) remains one of the most common indications for prescribing antimicrobial medications in the outpatient setting. Despite the extensive need for treatment of UTIs, the antimicrobial resistance rate has been rising, which has limited the therapeutic options. Application of basic knowledge can not only cure UTIs, but also prevent Clostridium difficile colitis and the development of multidrug-resistant organisms. For these reasons, primary care providers need to be knowledgeable and proficient in the diagnosis and management of UTIs. Three clinical cases, each with their own teaching points, are presented in this review.

KEYWORDS: Urinary tract infection, cystitis, pyelonephritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, antibiotics

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common bacterial infection encountered in the ambulatory care setting in the United States, accounting for 8.6 million visits (84% by women) in 2007.1 Acute cystitis is more common than acute pyelonephritis, with an estimated ratio of 28 cases of cystitis to 1 case of pyelonephritis.2

UTI is classified as either uncomplicated or complicated. In general, uncomplicated UTI refers to an acute illness of cystitis or pyelonephritis in healthy, premenopausal, nonpregnant women with no history to suggest abnormalities of the urinary tract.3 Complicated UTIs are those occurring in patients with a structural or functional abnormality of the genitourinary tract.4 The pathogenesis of UTI starts from periurethral mucosal colonization of pathogens that ascends the urethra to the bladder. Enteric organisms such as Escherichia coli are the most common culprits.

Acute cystitis usually manifests with dysuria, urinary frequency, urgency, suprapubic pain, hematuria, or combinations of these symptoms. Pyelonephritis should be suspected when a patient has fever, chills, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or nausea and vomiting in addition to symptoms of cystitis.5 Pyuria and bacteriuria are diagnostic. Dipstick testing is useful to assess the presence of leukocyte esterase and nitrates. Leukocyte esterase is an enzyme released by leukocytes and representing the presence of pyuria. Nitrates are metabolic products converted from nitrites by enteric organisms (eg, E coli). Of note, Enterococcus and Candida species do not produce nitrates. Urine culture testing is performed to determine the presence of bacteriuria and antimicrobial susceptibility.

Acute uncomplicated cystitis is a benign condition that rarely progresses to severe disease, even if untreated. Thus, the primary goal of treatment is to ameliorate symptoms.4 On the other hand, pyelonephritis can rapidly progress to urosepsis. Although most episodes of acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis are now treated in the outpatient setting, hospital admission should be considered if there is hemodynamic instability or any complicating factor such as diabetes, renal stones, or pregnancy. Other factors to consider for hospital admission include the patient’s inability to tolerate oral medications or a concern regarding nonadherence to treatment.4

Despite the extensive need for treatment of UTIs, the antimicrobial resistance rate has been increasing, which has limited the therapeutic options. For these reasons, primary care providers need to be knowledgeable about and proficient in the diagnosis and management of UTIs.

Case 1

A 45-year-old, community-dwelling, nondiabetic, nonpregnant woman presented with a 2-day history of dysuria, urinary hesitancy, urgency, and suprapubic pain. She denied fever, chills, rigors, back pain, nausea, and vomiting. Laboratory test results recorded 3 weeks previously had shown a serum creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL). She had no known drug allergy. She stated that this was her fourth episode of UTI in the past 8 months. Which antibiotic would be most appropriate in this patient’s case?

Discussion. Acute symptoms of dysuria, urinary hesitancy, urgency, and suprapubic pain are consistent with cystitis. Pyelonephritis is unlikely given the absence of additional symptoms of nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, back pain, or rigors.

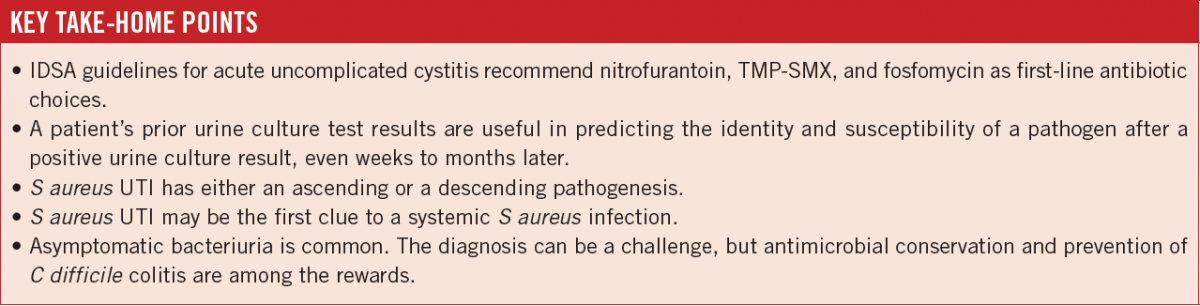

Management of acute uncomplicated cystitis is evolving as a result of increasing antimicrobial resistance.6 Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)7 emphasize the importance of considering ecologic adverse effects of antimicrobial agents (ie, selection for colonization or infection with multidrug-resistant organisms—so-called collateral damage) when selecting a treatment regimen. The IDSA guidelines recommend nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), and fosfomycin as the first-line regimen. All of these agents have good clinical efficacy (approximately 90%) with relatively favorable adverse effect profiles (Table). In patients with decreased renal function (glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min), nitrofurantoin may be a poor choice, since its efficacy diminishes along with declined creatinine clearance. The judicious use of TMP-SMX in a patient with decreased renal function is also recommended, because the antibiotic may induce undesirable hyperkalemia.

Many clinicians traditionally have prescribed fluoroquinolones as first-line agents, but they are no longer recommended as initial treatment for acute cystitis. Although fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin are highly efficacious for acute cystitis, they have propensity for “collateral damage.” For this reason, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for treating conditions other than acute cystitis and should be considered alternative antimicrobials for acute cystitis.7 Ultimately, the choice of antimicrobial agent should be individualized based on the following factors: the patient’s allergy and adherence history, local practice patterns, the prevalence of resistance in the local community, medication availability, and the patient and provider’s threshold for failure. If a first-line antimicrobial agent is not a good choice on the basis of one or more these factors, β-lactams or fluoroquinolones can be reasonable alternatives, although judicious use of these agents is recommended.7

Clinical selection of antibiotics is often influenced by medication cost to the patient, as well as patient comorbidities such as renal disease. Once these factors have been determined, the next best step in choosing an antibiotic is to review isolated organisms detected in previous urine culture tests. A patient’s prior urine culture test results are useful in predicting the identity and susceptibility of a pathogen after a positive urine culture result, even weeks to months later.8

Referral to a urologist should be considered for patients with recurrent UTIs to evaluate for underlying mechanical or functional urologic problems that would predispose them to infection. Regardless of external or internal reasons, obstruction of urine flow is the most important etiology of UTI. Urinary calculi may increase susceptibility to UTI, not only as a result of obstruction, but also as a result of a biofilm forming on the stones that enables the pathogens to survive despite antibiotic use. Antibiotic prophylaxis, an established method of UTI prevention, can be considered. Although cranberry juice has been promoted with the idea that associated acidification of the urine could treat and/or prevent recurrent infection, no convincing evidence exists to date that cranberry juice is effective in the treatment of urologic infection.9

Outcome of the case. The patient’s previous culture results were reviewed and were consistent with 1 UTI due to E coli and 2 UTIs due to Klebsiella pneumoniae during the previous year. The E coli isolates had been resistant to TMP-SMX but susceptible to nitrofurantoin. The K pneumoniae isolates were susceptible to both TMP-SMX and nitrofurantoin. No information was available about fosfomycin susceptibility for these isolates. A current urine culture was positive for E coli susceptible to nitrofurantoin; accordingly, oral nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, was selected as treatment, and the patient’s symptoms resolved. She was to be referred to a urologist for evaluation to rule out mechanical or functional urologic problems as the cause of her frequent UTIs.

NEXT: Case 2, Case 3, and Outcomes

Case 2

A 65-year-old, community-dwelling woman presented with a 2-day-history of fever, chills, fatigue, and right-sided “kidney pain.” On physical examination, the patient was febrile but was hemodynamically stable. Right costovertebral angle tenderness was noted. Urine dipstick test results were positive for leukocyte esterase and nitrates. Ciprofloxacin was prescribed empirically. In 24 hours, Staphylococcus aureus grew in the urine culture. During a follow-up telephone call the next day, the patient reported feeling unwell. How should this patient’s urine culture result be interpreted?

Discussion. This patient presented with fever, chills, and kidney pain, along with abnormal urinalysis findings suggestive of pyelonephritis. In such cases, an antibiotic with broad-spectrum in vitro activity against likely uropathogens should be started quickly to minimize progression of the infection. Although many cases of pyelonephritis can be managed on an outpatient basis, hospitalization is an option. A fluoroquinolone is the first-line antibiotic recommended for outpatient treatment of acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis, according to the IDSA guidelines.7 This patient received appropriate empiric regimen. But what is atypical about this case, and why did her condition not improve?

S aureus is a relatively uncommon cause of UTI in the general population.8 When a urine culture is positive for S aureus, clinicians need to consider from where this organism originated. An infection can reach the urinary tract via an ascending route or a descending route. A frequent mechanism for ascending infection with S aureus is an indwelling urinary catheter that has been colonized, a situation that is especially common in nursing home settings. S aureus bacteriuria can frequently lead to subsequent bacteremia.10 In this situation, catheter exchange and/or appropriate antibiotic management should be considered, even though this approach is controversial. The descending mechanism of infection with S aureus is clinically more important. Because urine originates from renally filtered serum, a bloodstream infection may first appear as a UTI. Results of a classic study showed that 17% of S aureus UTIs can be developed in this mechanism.11

Of note, S aureus bloodstream infection is a grave diagnosis. Crude 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortality rates have been reported as 28.8%, 37.5%, and 47.5%, respectively, in a study in Germany.12 S aureus is also the most frequent cause of infective endocarditis. Early detection of S aureus infection and optimization of treatment are keys for a better outcome. Input from an infectious disease consultant is well-known to improve outcomes, including a reported 56% reduction in 28-day mortality (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.22-0.89).13

Outcome of the case. The patient was hospitalized, and blood cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA). Echocardiography findings were consistent with vegetation on the mitral valve. She was received a diagnosis of MSSA native mitral valve endocarditis, and she was successfully treated with a 6-week regimen of parenteral cefazolin.

Case 3

An 80-year-old nursing home resident with a self-reported history of frequent UTIs presented to a primary care office to have her urine checked. She also had a history of confirmed recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis, which was currently in remission. She reported having completed a course of fosfomycin (3 g orally every 3 days for 2 doses) the previous day. At presentation, she was asymptomatic without fever, chills, back pain, nausea, dysuria, hesitancy, or suprapubic pain. She requested urinalysis to ensure that her urine is free of bacteria.

Results of a urine dipstick test were positive for nitrates and leukocyte esterase. Urine microscopic examination showed 20 white blood cells per high-power field, with rare bacteria. There were no epithelial cells present that would indicate contamination of the specimen.

A few days later, the urine culture had grown multidrug-resistant E coli susceptible only to intravenous antibiotics. Does this patient require hospital admission for intravenous antibiotics?

Discussion. Advanced age is associated with a higher incidence of UTIs. Occasionally, a UTI can be fatal. Interpreting a urine culture result in a patient without symptoms can be a challenge.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (AB) is defined as isolation of a specified quantitative count of bacteria in an appropriately collected urine specimen that has been obtained from a person without symptoms or signs referable to a UTI. According to the IDSA guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of AB in adults,14 AB in asymptomatic women is diagnosed based on 2 consecutive voided urine specimens with isolation of the same bacterial strain in quantitative counts greater than 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL. In asymptomatic men, a single clean-catch voided urine specimen with isolation of bacteria counts greater than 105 CFU/mL is sufficient for making a diagnosis of AB. Pyuria accompanying AB is not an indication for treatment. Pyuria is present with AB in approximately 32% of young women, 30% to 70% of pregnant women, 70% of diabetic women, 90% of elderly institutionalized patients, and 50% to 100% of individuals who have long-term indwelling catheters.14

AB is common, but its prevalence varies widely based on age, sex, and the presence of genitourinary abnormalities. For example, the prevalence of AB in healthy, premenopausal women is reported as 1% to 5%. However, the prevalence of AB in elderly persons in a long-term care facility reaches from 15% to 50%.14

In general, AB is a benign condition that is not associated with long-term adverse outcomes.14 Certain clinical scenarios needing aggressive screening and treatment include pregnant women and patients undergoing urologic procedures for which mucosal bleeding is anticipated, such as transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).14 Women identified with AB in early pregnancy have a 20- to 30-fold increased risk of developing pyelonephritis during pregnancy. These women also are more likely to experience premature delivery and to have infants of low birth weight.15 Patients with AB who undergo traumatic genitourinary procedures associated with mucosal bleeding have high rate of postprocedure bacteremia and sepsis. Bacteremia occurs in up to 60% of patients with bacteriuria who undergo TURP; there is clinical evidence of sepsis in 6% to 10% of these cases.16

AB is more problematic in the modern era, because antimicrobial resistance is widespread, and the pipeline of new antibiotics in development is nearly empty. The repeated use of different antimicrobial can select drug-resistant organisms as well as lead to the development of new drug resistance. Primary care providers have the biggest role in recognizing AB and conserving antimicrobials.

The first clue to the diagnosis of AB is a patient’s reported history of “frequent UTIs.” It is important to clarify with the patient whether he or she truly had UTI symptoms when cultures were obtained. Second, a review of longitudinal urine culture results is helpful. If the patient has a history of positive urine culture results without correlated symptoms, AB should be strongly suspected.

Outcome of the case. A full year of the patient’s urine culture results were reviewed, and 7 of 8 samples were culture-positive, mostly for E coli. The only negative urine culture result was one that had been obtained during a course of intravenous antibiotic therapy. When the patient was specifically asked about the presence of UTI symptoms, she denied ever having symptoms when past cultures had been obtained. This confirmed the diagnosis of AB.

Antibiotics for treatment of a UTI in such a patient should be avoided, which in turn will help reduce the risk of recurrence of C difficile colitis, reduce the development of multidrug-resistant organisms, and reduce health care costs.

Eiyu Matsumoto, MB, is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City, Iowa.

Jennifer R. Carlson, PA-C, is a physician assistant at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Iowa City, Iowa.

REFERENCES:

- Schappert SM, Rechtsteiner EA. Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2007. Vital Health Stat 13. 2011;(169):1-38.

- Kärkkäinen U-M, Ikäheimo R, Katila M-L, Siitonen A. Recurrence of urinary tract infections in adult patients with community-acquired pyelonephritis caused by E. coli: a 1-year follow-up. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32(5):495-499.

- Hooton TM. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1028-1037.

- Nicolle LE; AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-360.

- Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL, Fihn SD, Saint S. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2002;287(20):2701-2710.

- Grigoryan L, Trautner BW, Gupta K. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infections in the outpatient setting: a review. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1677-1684.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-e120.

- MacFadden DR, Ridgway JP, Robicsek A, Elligsen M, Daneman N. Predictive utility of prior positive urine cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(9):1265-1271.

- Nicolle LE. Cranberry for prevention of urinary tract infection? Time to move on. JAMA. 2016;316(18):1873-1874.

- Muder RR, Brennen C, Rihs JD, et al. Isolation of Staphylococcus aureus from the urinary tract: association of isolation with symptomatic urinary tract infection and subsequent staphylococcal bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(1):46-50.

- Lee BK, Crossley K, Gerding DN. The association between Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and bacteriuria. Am J Med. 1978;65(2):303-306.

- Hanses F, Spaeth C, Ehrenstein BP, Linde H-J, Schölmerich J, Salzberger B. Risk factors associated with long-term prognosis of patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infection. 2010;38(6):465-470.

- Honda H, Krauss MJ, Jones JC, Olsen MA, Warren DK. The value of infectious diseases consultation in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):631-637.

- Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654.

- Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when to screen and when to treat. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17(2):367-394.

- Grabe M. Antimicrobial agents in transurethral prostatic resection. J Urol. 1987;138(2):245-252.