Complications of Multiple Magnet Ingestion

Intestinal Perforation After Ingestion of 2 Desk Toy Magnets

A 2-year-old boy had worsening, intermittent emesis for the past 5 days. On the day of presentation, he had 10 episodes of green, nonbloody emesis and a fever, temperature 39ºC (102.2ºF). When his symptoms first began, he was evaluated by his primary care practitioner who diagnosed acute otitis media and prescribed amoxicillin. The symptoms progressed and moderate to severe periumbilical and lower abdominal pain developed. The pain did not seem to radiate to the back or testes. The parents also noticed abdominal distention. The child’s last bowel movement was about 2 days earlier. He had a mild runny nose and cough. There was no history of neck pain or rashes.

In the emergency department, the patient was crying and appeared uncomfortable. He had a soft abdomen, without rebound or guarding, and generalized tenderness. Abdominal ultrasound findings were normal. Laboratory studies, including a hemogram, electrolyte and lipase levels, liver function tests, and urinalysis, were unremarkable. After a failed oral fluid challenge, the child was hospitalized for intravenous hydration.

An abdominal radiograph revealed 2 metallic foreign bodies (A). There was also free intraperitoneal air in the upper abdomen with moderately dilated small bowel loops, suggestive of an ileus or developing small bowel obstruction.

On further questioning, the mother admitted to purchasing a high-powered magnet desk toy for the child’s father a year ago.

Surgical consultation for suspected intestinal perforation was urgently acquired. During laparoscopy and exploratory laparotomy, free purulent fluid was noted that appeared to have intestinal small bowel contents. Erosion through the ileal mesentery and perforation of the ileum, jejunum, and cecum were evident. The appendix and part of the cecum were removed, and 2 magnets were extruded. Part of the distal ileum was resected and reanastamosed.

Peritoneal fluid culture grew Streptococcus milleri. Ampicillin/sulbactam and metronidazole were started, and the patient had an uneventful postoperative course. The family was informed of the lifelong risk of adhesive bowel obstruction after exploratory laparotomy. The child was discharged after 5 days. At follow-up a month later, he was doing well.

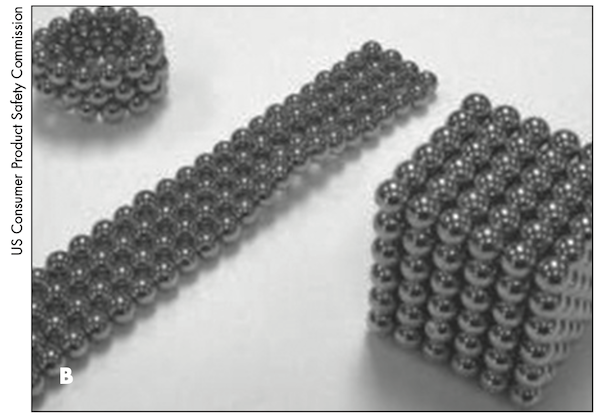

Foreign body ingestion is a common cause of morbidity in children, especially in those younger than 3 years.1,2 Magnet ingestion is rare and its complications even rarer, with fewer than 50 cases requiring surgical intervention.3 Over the past few years, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has received numerous reports of ingestion of high-powered magnets marketed as desk toys (B). On July 25, 2012, the CPSC sued the maker of the desk toys alleging defects in the product, packaging, and warnings (Release #12-234) and called upon retailers to cease distribution of these products in an effort to prevent further harm to children.

Children who have ingested a foreign body may present with a variety of clinical symptoms, including abdominal pain, distention, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and even lethargy. Fever is a worrisome sign because it may suggest complications, such as deep mucosal ulceration and perforation.4,5 Other possible complications include small bowel necrosis or obstruction and fistula formation. Volvulus of the small and large intestine and strangulation of adjacent loops also have been reported.6

Magnets may be visible on plain radiographs; however, one must be aware that multiple magnetic objects may erroneously be reported as a single unit.7 Plain abdominal films may show bowel loop distention and air-fluid levels in patients with intestinal obstruction, and pneumoperitoneum in those with bowel perforation.

About 80% to 90% of foreign bodies spontaneously pass through the GI tract, 10% to 20% are removed endoscopically, and 1% require surgical intervention.1,5 Magnet ingestion needs special consideration because of its significant associated morbidity and mortality.2 For single or multiple magnets in the stomach, endoscopic retrieval is often recommended.4,6-8 Management of multiple magnets that have already passed the pylorus is controversial. Some authors recommend prompt surgical intervention.1,8,9 Others suggest close observation and serial imaging to monitor for obstruction, perforation, or unchanged magnet location.4,10

Pediatric and general practitioners who provide anticipatory guidance about the potential hazards of magnetic toys can help prevent magnet ingestions.

REFERENCES:

1. Lee SK, Beck NS, Kim HH. Mischievous magnets: unexpected health hazard in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(12):1694-1695.

2. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, et al. 2010 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 28th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:910-941.

3. Kabre R, Chin A, Rowell E, et al. Hazardous complications of multiple ingested magnets: report of four cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19(3):187-190.

4. Hernández Anselmi E, Gutiérrez San Román C, Barrios Fontoba JE, et al.

Intestinal perforation caused by magnetic toys. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(3):

E13-E16.

5. Kay M, Wyllie R. Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr

Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7(3):212-218.

6. Robinson AJ, Bingham J, Thompson RL. Magnet induced perforated appendicitis and ileo-caecal fistula formation. Ulster Med J. 2009;78(1):4-6.

7. Butterworth J, Feltis B. Toy magnet ingestion in children: revising the algorithm. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(12):e3-e5.

8. Shah SK, Tieu KK, Tsao K. Intestinal complications of magnet ingestion in children from the pediatric surgery perspective. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19(5):

334-337.

9. Oestreich AE. Multiple magnet ingestion alert. Radiology. 2004;233(2):615.

10. Chung JH, Kim JS, Song YT. Small bowel complication caused by magnetic foreign body ingestion of children: two case reports. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(10):

1548-1550.

Intestinal Obstruction From Multiple Magnets

A 3-year-old boy was brought to the hospital because of multiple episodes of nonbilious emesis over 3 days. In the emergency department (ED), the child was afebrile and had no diarrhea. He appeared dehydrated and was treated with intravenous fluids. Examination revealed generalized abdominal tenderness. The abdomen had no rigidity or palpable masses. Sluggish bowel sounds were heard on auscultation.

Abdominal radiographs revealed multiple radio-paque foreign objects (C and D). On further questioning, the patient denied ingesting anything. The objects were suspected to be magnets because of their length and beaded appearance. Pediatric general surgery was consulted given the persistence of symptoms and the risk of multiple magnet attraction from within and across the bowel loops causing obstruction. During laparotomy, 8 small magnets were removed. Closer inspection of the bowel loops revealed signs of necrosis.

Bowel obstruction caused by multiple magnet ingestion has been described.1,2 Children may ingest a wide range of nonfood foreign objects. Those that reach below the level of diaphragm tend to pass spontaneously without intervention, although large or sharp objects may not pass successfully. Small foreign bodies such

as hairs can become entangled and lead to intestinal obstruction in children.3 Coins or disc batteries may become impacted at either the proximal or distal esophagus and often require endoscopic removal.

Many children’s toys contain magnets. These come in various sizes and shapes (E). The US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has issued a safety alert for such toy-related hazards (Release #07-163). Magnet-containing toys have been recalled in the past—Magnetix Magnetic Building Sets by Rose Art Industries Inc/Mega Brands America, Inc were recalled in March 2006 (Release #06-127) and Polly Pocket Magnetic Play Sets by Mattel, Inc were recalled in November 2006 (Release #07-039). The CDC has also highlighted the hazards related to magnetic ingestion in children.4 Despite the recalls, manufacturers continue to release toys with small objects that put children at risk for accidental ingestion.

It is important to maintain a low threshold when considering magnet ingestion and be cognizant of the potential for multiple magnets.2 The attraction of 2 magnets (or a magnet and a metal coingestant) across intestinal walls may cause obstruction within and outside the lumen. This can lead to mucosal ischemia, pressure necrosis of the intestinal wall, and possible perforation. Fistula formation is not uncommon. Intestinal volvulus has also been reported secondary to magnet ingestion.1

Although routine abdominal radiographs can uncover the radio-paque nature of a foreign body, they do not reveal any information about its magnetism.

Having a metal detector and a magnetic compass in the ED could aid in defining the properties of ingested foreign bodies.5 This may not only help support diagnoses of ingested metals and magnets but also help prevent complications from delay in diagnosis in cases without a definitive history.

An increased effort to educate caregivers about the potential hazards of toys with small magnets is needed. These hazards can often be discussed during an ED visit via a pamphlet or educational handout.

REFERENCES:

1. Ilçe Z, Samsum H, Mammadov E, Celayir S. Intestinal volvulus and perforation caused by multiple magnet ingestion: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37(1):50-52.

2. Butterworth J, Feltis B. Toy magnet ingestion in children: revising the algorithm. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(12):e3-e5.

3. Malhotra A, Jones L, Drugas G. Simultaneous gastric and small intestinal trichobezoars. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(11):774-776.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gastrointestinal injuries from magnet ingestion in children—United States, 2003–2006. MMWR. 2006;55(48):1296-1300.

5. Conners GP. Diagnostic uses of metal detectors: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(8):946-949.