Childhood Depression: Recognition and Management

ABSTRACT: Child and adolescent depression is a disorder with a high prevalence and significant morbidity that is often encountered by primary physicians. Screening and initiating treatment and referrals for depression and other childhood mental health disorders has fallen on the primary pediatrician’s shoulders. Children with symptoms suggestive of depression and all adolescents regardless of reported symptoms should be screened for depression. Diagnosis and management of depression is a multidisciplinary task that involves the family and community partners, including schools and mental health agencies. Psychotherapy should always be considered an initial intervention for mild to moderate depression. Medication may be a first-line response when the symptoms of depression are debilitating and immediate treatment is necessary to restore functioning. Depression is a treatable but chronic disorder that requires long-term monitoring and follow-up.

Timothy is a 7-year-old boy who is brought to the general pediatric clinic for changes in mood and behavior over the past 3 months. His teachers have noticed that he is more irritable and has begun talking back to them. While previously an average-performing student in a mainstream classroom, Timothy’s school performance has declined with frequent incomplete assignments. His mother reports that he has been complaining of stomachaches often and that he doesn’t ask to go on play-dates with his friends. On further questioning, you learn that his mother has a history of depression, but is no longer taking medication for it, and his parents separated a year ago. Timothy saw a counselor at school about this for a month but stopped going.

“He’s so young, he can’t possibly be depressed” and “It’s just a phase, he should outgrow it” are common myths about childhood depression that at one time might have been used to describe the child in this scenario. In the first half of the 20th century, young children were thought to be incapable of truly experiencing depression because of immaturity of the personality system.1 Traditional developmental theory in the mid-20th century held that the child’s superego was unable to feel guilt required for depression.2

It is now widely regarded that childhood depression is a real entity (perhaps clinically distinct from the adult form) that can be pervasive and even life-threatening.3,4 Although childhood may be viewed as a carefree period of life, children must contend with the pressures of peer acceptance, school life, and internal (self) and external (parental) expectations on a daily basis. Children are also privy to stressful information in the media and in families and communities. Death, separation, and loss affect children just as they do adults.

Symptoms that extend beyond what is typical for grief and bereavement and adjustment to stressors cannot be considered a “phase” in children. These symptoms can be manifestations of depression and can worsen into adolescence and adulthood. Moodiness associated with functional impairment in a teenager should not be considered “normal” teenage behavior; and teenagers with depression are more likely to have mood disorders as adults.5

Here, we will review the recognition and management of unipolar major depression as it manifests in children and adolescents. A discussion of bipolar depression is outside the scope of this article.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) provides a specific set of criteria for depressive disorders, which are clumped under mood disorders.6 These include the following:

•Mood episodes: major depressive episode, hypomanic episode, manic episode, mixed episode.

•Depressive disorders: dysthymic disorder, major depressive disorder—single episode, recurrent, and depressive disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).

•Bipolar disorders: bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, bipolar disorder NOS.

•Mood disorder due to a general medical condition with depressive features, manic features, or mixed features.

•Substance-induced mood disorder.

•Mood disorder NOS.

The newest version of the manual (DSM-5, due out in 2013) has a greater emphasis on developmental trajectories of mental disorders. For depression, the proposed revisions include removing the bereavement exclusion7 and adding criteria for a mixed features specifier. The DSM-5 Child and Adolescent Disorders Work Group is considering eliminating the “irritability” criterion. At this point, depression is not included in the section on conditions that manifest in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. The DSM-IV provides alternate criteria for child and adolescent depression (Table 1).

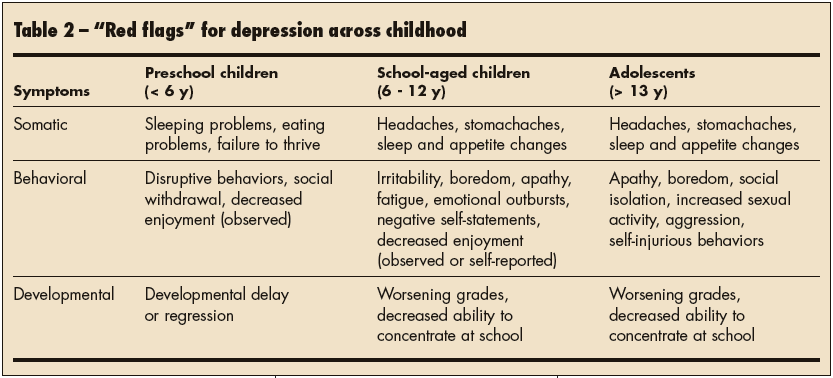

Clinicians need to recognize that children may not verbally disclose depression and that red flags for potential depression vary by developmental age (Table 2). Typical depressive symptoms seen in adults may manifest in later childhood and adolescence. However, in some cases, even younger children may manifest the typical depressive symptoms seen in adults.8 Good history taking is essential in this regard because both typical and masked symptoms may not spontaneously be described by either the child or the primary caregiver.

RECOGNITION OF DEPRESSION

RECOGNITION OF DEPRESSION

Why is it important? The point prevalence of depression is thought to be about 2% in children and 4% to 8% in adolescents.5 Adolescents aged 13 to 18 years have a lifetime prevalence of 11.2% for depression.9 Therefore, depression is a relatively common disorder that is likely to be encountered by the general pediatrician in clinical practice.

When untreated, depression causes low self-esteem and self-confidence, social withdrawal and isolation, and worsening of learning problems. Teenagers with depression are at increased risk for alcohol and substance abuse, usually 4 to 5 years after the onset of depression. They may also experience impaired functioning in school and with interpersonal relationships,5 which puts them at increased risk for alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide. In addition, 5% to 10% of children and adolescents with subsyndromal symptoms of depression are at increased risk for major depressive disorder and suicide.10,11

Most importantly, Hatcher and King12 reported that up to 85% of teenagers with depression have suicidal ideation and up to 32% attempt suicide. In 60% of teenagers who commit suicide, a depressive disorder had been diagnosed. Suicide is the third leading cause of death in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years. The rate of suicide is lower in prepubertal children with depression; however, some evidence suggests that the prevalence of depression may be increasing overall with an earlier age of onset.12 Untreated depression may remit within 6 to 8 months, with between 40% and 70% recurrence within 5 years.13,14 Early and effective intervention may decrease the impact depression has on the child’s life and may prevent future substance abuse or suicide.

Why be involved? The primary care pediatrician is an important guardian of both physical and emotional health in children and adolescents. Regular well-child checks provide important opportunities to screen for any potential mood disorders, including depression. Primary physicians are usually the first point of contact when parents or school personnel raise concerns about a child’s behavior. Families and teens are more likely to approach a physician than a mental health professional for an evaluation of symptoms associated with a possible psychiatric disorder. This may be due to the somatic nature of their complaints or the stigma associated with mental health disorders.15 In addition, the primary physician is often the gatekeeper to additional resources when dealing with insurance authorizations.

Due to a widespread shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists and developmental-behavioral pediatricians, screening and initiating treatment and referrals for depression and other childhood mental health disorders has fallen on the primary pediatrician’s shoulders.16 In 2001, the number of available child psychiatrists per 100,000 children ranged by state from 3.4 to 21.3, with a national mean of 8.7.17 In 2006, fewer than one developmental-behavioral pediatrician was available for every 100,000 children in the United States.18 The wait times and insurance limitations are other barriers to patients receiving care from these specialists.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Bright Futures Handbook (www.brightfutures.aap.org) includes screening for depression as part of the anticipatory guidance and surveillance recommendations. However, many general practitioners still feel ill-equipped to recognize or manage mood disorders, such as depression.19 The time demands of a general pediatric practice along with the need to cover issues of physical health and well-being make the management of childhood depression a challenge.20 Studies show that less than 50% of adults with onset of depression in childhood or adolescence sought care before 18 years of age,21 and up to 70% of children and adolescents with depression and anxiety may be missed by primary care clinicians.22

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT

Screen for depression. Over the past 10 years, regular developmental screening has become increasingly adopted in general pediatric practice.23 A similar approach can be taken with mental health issues. At a minimum, children with symptoms suggestive of depression and all adolescents regardless of reported symptoms should be screened.

Research has shown that an affirmative answer to the 2 following questions may be as effective as longer screening tools:

•“Over the past 2 weeks, have you felt down, depressed, or hopeless?”

•“Have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things?”24,25

Depending on the age of the child, these questions may not be relevant. Therefore, a more formalized screening tool is recommended, and multiple reporters (eg, parent or teacher) may be required. It has been well documented that relying on clinician intuition alone is notoriously insensitive and that screening tools increase sensitivity for behavioral problems by 70%.26 Screening tools can be broad-based for a variety of mood and behavior problems or depression-specific. Table 3 lists a selection of screening tools that can be used in children and adolescents. Results of screening alone are inadequate to make a positive diagnosis; they raise concerns, stimulate discussion with the family, and prompt referrals to appropriate resources for a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation performed by a mental health professional.

Screening for depression is billable under the CPT code 96110, “limited developmental testing with interpretation and report.” Multiple screens performed on the same visit may be coded under modifier 59, “distinct procedural services,” or modifier 25, “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service above and beyond the other service provided.” We encourage pediatric practitioners to investigate the billing and reimbursement options that are most appropriate for their organizations and patient populations, consistent with their procedural activities.

Screening for depression is billable under the CPT code 96110, “limited developmental testing with interpretation and report.” Multiple screens performed on the same visit may be coded under modifier 59, “distinct procedural services,” or modifier 25, “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service above and beyond the other service provided.” We encourage pediatric practitioners to investigate the billing and reimbursement options that are most appropriate for their organizations and patient populations, consistent with their procedural activities.

Be aware of comorbidities. The psychiatric differential diagnosis for depression includes anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and dysthymia, among others. However, children who screen positive for depression frequently exhibit concurrent symptoms of other psychiatric disorders. In fact, 40% to 90% of children with major depressive disorder have at least one co-occurring disorder, and 30% to 50% have 2 or more psychiatric disorders.5,27 This high rate may be explained by a number of different theoretical mechanisms: the developing brain may be particularly vulnerable to multiple psychiatric disorders; there may be a shared etiology among different psychiatric disorders; one psychiatric disorder may decrease the threshold for developing others; or psychiatric disorders in childhood may represent clinically distinct entities from the adult counterparts. The most common comorbidities with depression are dysthymic disorder (50% to 80%); anxiety disorder (30% to 50%); disruptive behavior disorders, such as ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (10% to 50%); substance abuse disorder (20% to 30%); and eating disorders.28,29

Research has also established that children of depressed parents (particularly mothers) are at increased risk for behavioral problems, anxiety, attachment disorders, and depression.30-32 The presence of coexisting psychiatric problems in the caregiver has important implications for intervention, because multigenerational therapy has been shown to be helpful in cases of co-occurring depression.33 Postnatal depression can be considered if the mother is pregnant or has given birth to another child within the past year.

Awareness of the factors surrounding the diagnosis of depression can help inform the pediatrician’s approach to the patient. Depending on the clinical scenario, broad-based rather than depression-specific screening tools may be indicated. The information obtained from the screening tools can help the physician identify potential comorbidities and make appropriate referrals. Clinicians may also consider administering an adult-based screening tool to the patient’s caregivers.

Explore the medical differential diagnoses. Suspicion of depression in a child or adolescent warrants a thorough history and physical evaluation for medical disorders that can present with symptoms of fatigue, mood changes, or cognitive changes.

Seizure disorders and metabolic diseases can present with regression of previously acquired developmental milestones or deteriorating school performance. Concussions after head injuries may manifest as nonspecific symptoms, including headaches, mood changes, new onset attention problems, and changes in eating or sleeping patterns; they are also associated with increased rates of depression. Infections, such as infectious mononucleosis and primary HIV infection, can cause general malaise and decreased energy. Endocrine disorders (diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism) can affect mood, energy level, and behavior. Nutritional deficiencies that lead to anemia, such as iron and vitamin B12 deficiencies, can present with decreased energy and changes in behavior. Sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea) can result in excessive somnolence, irritability, attention difficulties, and headaches.

Medication use or abuse can also mimic depression. Corticosteroid use may be associated with increased appetite and mood lability. Children taking benzodiazepines may present with decreased energy, increased sleep, and general apathy. Anticonvulsants may cause cognitive slowing (eg, topiramate) and mood or behavior changes (eg, levetiracetam); they can also increase the risk of depression (eg, phenobarbital, phenytoin). Other medications that have been associated with depression include isotretinoin, interferon, calcium channel blockers, ß blockers, oral contraceptives, statins, and fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Substance abuse should always be investigated as a possible contributing factor (or complication) of depression.

Finally, children with chronic medical illnesses are also at increased risk for depression. CNS disorders, such as epilepsy, migraines, and irritable bowel syndrome, are closely associated with depression. Increased rates of depression in asthma and sickle cell anemia have also been described.34

Concerns for a potential medical cause of presenting symptoms should prompt a more targeted work-up. Depending on the clinical scenario, the clinician can consider obtaining laboratory studies, including a complete blood cell count, thyroid function testing (free thyroxine and thyroid stimulating hormone), electrolyte levels, urine toxicology, and kidney or liver function testing.

MANAGEMENT

When the decision has been made to treat depression, it is important to discuss the different options with the patient and family. Psychotherapy should always be considered an initial intervention for mild to moderate depression, and it may be sufficient for symptom management. Medication may be considered a first-line response when the symptoms of depression are debilitating and immediate treatment is necessary to restore functioning and prevent immediate and/or severe consequences. However, it is usually considered only after a comprehensive and competent trial of psychotherapy of at least 3 months duration. The Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health demonstrated that the combination of medication and psychotherapy is the most effective treatment for adolescents with depression,35 although a meta-analysis has suggested that the benefit of combination therapy is seen only with short-term improvements in level of function.36

Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy may be offered by a variety of mental health professionals, including psychologists, social workers, marriage or family therapists, and pastoral counselors. It may be implemented individually, in groups, or in a family environment. Interventions should emphasize the treatment of a family rather than an individual, especially with younger children. A multigenerational approach may be particularly helpful if there are concurrent psychiatric disorders in the child’s parents. Play therapy has been popular with younger children but has not been supported by systematic studies. Older children can benefit from a peer group approach.

A basic knowledge about the kinds of psychotherapy used in children and adolescents is helpful when looking to partner with a mental health provider. The content of psychotherapy depends on the overall approach of the therapist, the developmental age of the child, and the specific challenges in their symptom make-up.

Cognitive psychotherapy is designed to alter negatively-based cognitions. Depressed patients are trained to:

•Recognize connections between their thoughts and feelings and their behavior.

•Monitor and challenge their negative thoughts.

•Substitute negative thoughts with reality-based interpretations.

Behavioral psychotherapy is designed to increase pleasant activities by self-monitoring activities and mood. Patients are trained to first identify and then reinforce activities associated with positive feelings and decrease negative activities.

Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy combines the 2 separate elements of the cognitive and behavioral approaches; it has been shown to be effective for the treatment of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and eating disorders.

Social skills training teaches children how to initiate conversations, respond to others, and make requests. Children are provided with instructions and modeling by an individual or peer group with opportunities for role playing and feedback.

Self-control therapy provides strategies for self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-reinforcement.

Interpersonal therapy focuses on relationships, social adjustment, and mastery of social roles.

Psychopharmacology. Table 4 lists the pharmacologic agents used to treat depression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the most common antidepressant medication, have demonstrated similar efficacy and side effect profiles when compared in studies in adults. Fluoxetine is FDA approved for the treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Escitalopram is FDA-approved for the treatment of adolescent depression, although the approval was based on the results of a single randomized controlled trial.37

Psychopharmacology. Table 4 lists the pharmacologic agents used to treat depression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the most common antidepressant medication, have demonstrated similar efficacy and side effect profiles when compared in studies in adults. Fluoxetine is FDA approved for the treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Escitalopram is FDA-approved for the treatment of adolescent depression, although the approval was based on the results of a single randomized controlled trial.37

A patient typically needs to be treated for 3 to 4 weeks before the efficacy of the SSRI is appreciated. A full response may take 8 to 12 weeks, although this varies significantly per individual. The mantra of “start low and go slow” is appropriate for the treatment of childhood depression, with weekly increases until a minimum effective dosage is established. If side effects develop and persist more than 1 week, the dosage should be adjusted to the highest tolerable dose. Treatment response should be reevaluated every 4 to 6 weeks; if the response is not optimal, the dose should be increased. If one SSRI fails, a second SSRI should be considered before switching to a non-SSRI medication.38

Screening laboratory studies or ECGs are not required before starting SSRIs. While some side effects of SSRIs can be transient, others may be long-lasting. Thus, preemptive counseling is vital before beginning a trial of therapy. Headaches and nausea are fairly common when starting an SSRI but usually resolve after a short time. Sexual dysfunction is common in adolescents and reversible when the medication is stopped. Nervousness, trouble falling asleep, and nighttime awakenings can occur during the first few weeks. Some children appear restless and may have behavioral activation (restlessness, disinhibition).

Persistent symptoms may respond to lowering the dose or changing to another medication. There is also the possibility of inducing a manic episode in patients who are predisposed to bipolar disorder; this is characterized symptoms of grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, pressured speech, flight of ideas, distractibility, and excessive seeking of pleasure. Any of these side effects may be amplified when an SSRI is combined with other medications that affect serotonin, such as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. The FDA also has reported an increased risk of bleeding for fluvoxamine, citalopram, escitalopram, and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors when taken with other drugs that prevent blood clots, such as aspirin. The most extreme adverse reaction of SSRIs is serotonin syndrome, which can be life threatening. It is characterized by fever; confusion; muscle rigidity; and cardiac, liver, or kidney disorders.

In 2004, the FDA adopted a black box warning to indicate that antidepressants may increase risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in some children and adolescents with depression. In 2006, the FDA extended the warning to include young adults to age 25. A recent review of nearly 2200 children treated with SSRIs demonstrated no completed suicides. However, 4% of patients taking the medications had suicidal thinking or behavior, including actual attempts, twice the rate of those taking placebo. These effects mostly occurred within 4 weeks after starting the drug. As a result of the black box warning, the rates of SSRI use dropped, and researchers noted a concomitant increase in suicides and suicidal behavior in the population.39

When compiling these different lines of evidence, we suggest that the benefits of antidepressant medications probably outweigh the risks to children and adolescents with major depression and anxiety disorders. However, children and adolescents taking SSRIs should be closely monitored for any worsening of depression, new suicidal thinking or behavior, or unusual changes in behavior (sleeplessness, agitation, or withdrawal from normal social situations), especially within the first 4 weeks of treatment.

Non-SSRI treatment options, such as nefazodone and venlafaxine, are considered second-line. Tricyclic antidepressants have largely fallen out of favor for the treatment of depression because of their significant side effects (particularly cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death) and the risks of toxicity with overdose; they have shown marginal efficacy for adolescents and little efficacy for children.40 Ongoing clinical trials are being conducted with duloxetine, selegiline, desvenlafaxine, and riluzole.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). For a variety of reasons, families may choose CAM rather than conventional prescription medication. Studies show that CAM has been used more than conventional therapies in the treatment of adult depression,41 with an overall increasing trend of use.42 Therefore, it is important that clinicians anticipate questions about CAM options and inquire directly if the family is using any form of this therapy. Knowledge of commonly used CAM is also helpful. Pediatricians should remind parents that CAM is not regulated by the FDA and that herbal supplements may be of variable potency and purity.

St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) is a popular herbal remedy that has shown mixed effectiveness in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. However, the herb interferes with hepatic metabolism and can affect serum drug levels of other medications, including oral contraceptives and drugs used to treat mood disorders.

Omega-3 fatty acids have shown some promise for the treatment of depression, and there are ongoing clinical trials to assess their potential efficacy and toxicity.

WORKING WITH OTHER SYSTEMS OF CARE

Schools play an important role in the management of child and adolescent depression. They are a valuable source of information as well as a less-stigmatizing venue for therapy. Teachers may be the first to notice a change in behavior or school performance and can provide data regarding recovery or relapse. With their focus on academic achievement, schools should be committed to the identification and effective treatment of psychiatric illness. Pediatric practitioners should stay informed about interventions at the child or adolescent’s school, including the involvement of guidance counselors and therapists. They should also know whether modifications under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (www.dol.gov/oasam/regs/statutes/sec504.htm) or an Individual Education Plan are necessary for significant impairment in school function.

Because psychotherapy is the first line of treating mild to moderate depression, it is important to know the options for psychotherapy available in the community as well as the training, expertise, and comfort-level of various local mental health professionals. The primary care office should have active lines of communication with the mental health professionals to insure coordination of care.43 The most effective treatment is based on a collaborative care model, which consists of a multidisciplinary team of a primary care practitioner, a mental health specialist, and a case manager.44

The AAP and American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Task Force on Mental Health recommends colocation of mental health professionals in the primary care setting,45 in which both professionals operate in the same clinic space. This close proximity enhances provider collaboration and communication, which may lead to improved outcomes in both physical and mental health. The benefits of colocation have mostly been studied in the military population, although models for colocation of pediatric mental health services exist.46

FAMILY EDUCATION

FAMILY EDUCATION

It is critical to involve both the child or adolescent and the family members in any discussions regarding the diagnosis and treatment of depression. Mental health issues can be a sensitive topic. An understanding of parental perceptions of depression can provide guidance regarding the complex interplay of genetics, environment, and biochemical factors. Clinicians and families should affirm the patient’s value as a human being, particularly if he or she expresses feelings of worthlessness.

Clinicians should address the common myths of childhood and adolescent depression and the multidimensional effects of untreated depression. It is important to stress the importance of family support and therapy so that the patient does not feel singled-out. Depression should be presented as a treatable disorder that can recur in the future. Educational resources for families are listed in the Box.

REFERRAL AND ASSISTANCE

The decision to refer a patient with depressive symptoms must be weighed against the shortage of psychiatric and developmental-behavioral specialists and the tremendous burden of the disorder. At minimum, pediatric practices should provide screening and triage of depression. Practices that are more familiar with the use of antidepressant medications may choose to collaborate with mental health professionals while attempting a trial of therapy. Failure to respond to an SSRI, emergence of possible mania or hypomania, uncertainty about the diagnosis or potential comorbid conditions, and suicidal behavior signal the need for referral to a child psychiatrist or developmental-behavioral pediatrician.

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression - Primary Care, published in 2007, include a suggested clinical flowchart and additional depression-specific screening questionnaires for use in primary care. These guidelines are available for free online at www.glad-pc.org. In 2010, the AAP Task Force on Mental Health released a number of resources to help practices develop systems of care to deal with mental health issues. The products of this task force are available online (www2.aap.org/commpeds/dochs/mentalhealth/mh2ch.html) and include strategies for working with families and mental health professionals, algorithms for addressing mental health, and templates for communicating with outside collaborators.