Changing and Maintaining Health Behaviors: Adherence and Compliance Issues

Healthy behaviors such as smoking cessation, adherence to a healthful diet, and regular physical activity are important for overall health status and quality of life in older adults. These modifiable healthy behaviors have all been associated with the prevention of chronic diseases (eg, heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes),1 all of which are leading causes of morbidity and mortality in older adults and impact quality of life.2 In addition to the individual impact of having chronic illnesses, the economic burden for society is significant in that 95% of all healthcare expenditures are for management of these illnesses.1

There are many guidelines for healthy behaviors established through organizations such as the American Heart Association and the American College of Sports Medicine for exercise,3 and the United States Department of Agriculture for dietary recommendations.4 The decisions about whether or not to recommend these guidelines to older patients are complicated by factors such as the provider’s beliefs about the benefits given the individual’s age, life expectancy, and/or quality of life, and the time challenge of incorporating health promotion into routine medical visits. For older adults, adherence is further compromised by numerous factors intrinsic to the individual (eg, motivation, cognitive status) and extrinsic (eg, environment, financial resources). Understanding what influences adherence to healthy lifestyles is critical so that healthcare providers, families, lay caregivers, and friends can help older individuals optimize adherence, improve quality of life, and help control healthcare costs.5

Prevalence of Nonadherence to Healthy Behaviors

The rate of nonadherence to healthy behaviors varies greatly across the type of behavior being considered. Only a small percentage of older adults smoke (< 10%), although annually 70% of older smokers want to quit, and 46% are quite successful in doing so.6 When comparing physical activity to other health behaviors such as diet and smoking cessation, older adults are less likely to adhere to regular physical activity.7 Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System,8 less than one-third of older individuals engage in regular physical activity, with the proportion meeting recommended guidelines dropping with advancing age. Likewise, data on 710 women from the Women’s Health and Aging study indicated that only 13% of these individuals meet the required 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity.9 With regard to adhering to healthful diets, 11.2-63.3% of adults meet healthful diet recommendations as per the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.10

Even in persons previously identified as high-risk for specific medical problems such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), the health behaviors necessary to decrease risk factors are not adequately managed.11 In a sample of 364 community-dwelling stroke survivors age 34-88 years old, 99% of the participants had at least one suboptimally controlled risk factor, and 91% had two or more concurrent risk factors that were inadequately treated.12 Eighty percent of the participants had prehypertension or hypertension, 67% were overweight or obese, 60% had suboptimal low-density lipoprotein, 45% had impaired fasting glucose, 34% had low high-density lipoprotein, and 14% were current smokers.

Adherence to Multiple Health Behaviors

Given the many health behaviors that older adults are encouraged to adhere to, it is important to consider whether adherence to one is more likely to increase or decrease adherence to a second behavior. Generally, findings suggest that those who engage in one healthy behavior are more likely to adhere to other health-promoting behaviors.13,14 For example, older individuals who adhere to regular exercise and healthful diets are more likely to adhere to medications (eg, statins, antihypertensives) to prevent progression of CVD.13

Current recommendations15 generally support implementing simultaneous behavior change interventions versus sequential or single behavior change around physical activity, smoking cessation, and diet in adults. Addressing multiple behaviors at one time results in an efficient approach to behavior change in that teaching can focus on general behavior change principles such as how to cope with barriers, work with a partner, or establish goals and rewards.16 Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that individuals tend to express an interest in changing multiple behaviors rather than focus on a single behavior.17 Specifically, adults with CVD were noted to be more likely to choose both strength training and weight reduction to decrease their risk for CVD than to focus on a single behavior,17 and those with dyslipidemias were likely to change both diet and physical activity as a way to improve blood lipids.

Factors That Influence Adherence to Healthy Behaviors Among Older Adults

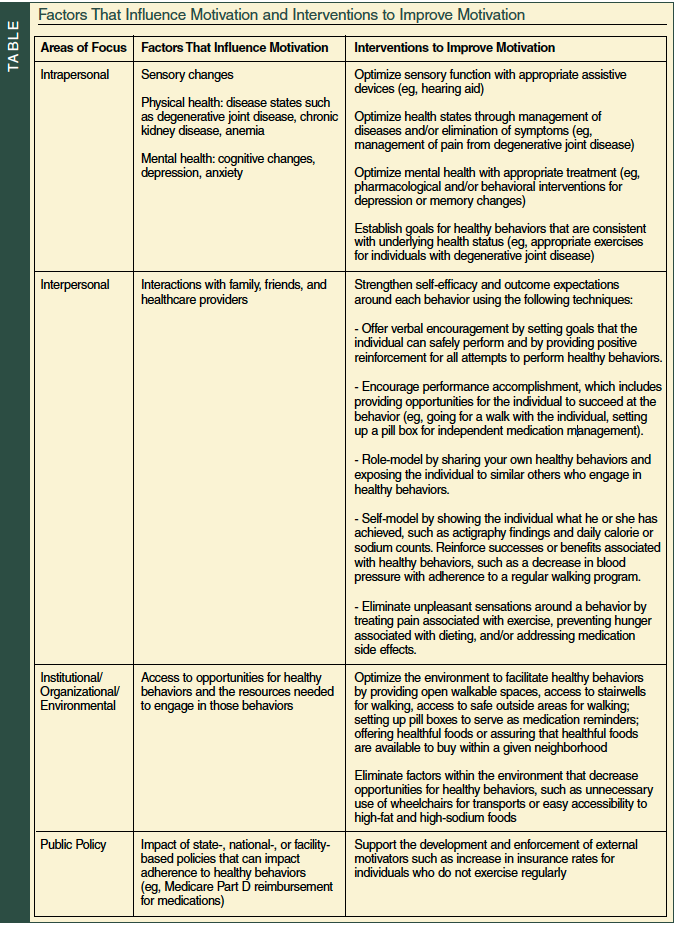

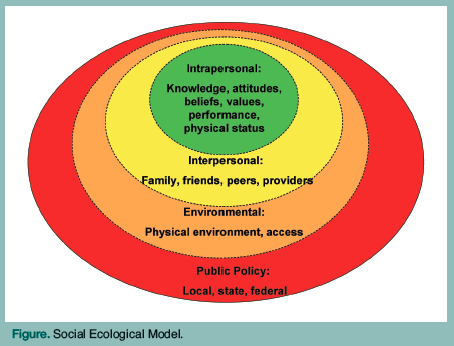

The reasons for poor adherence to health-promoting behaviors among older adults are multifactorial, and therefore most comprehensively considered using a social ecological model (Table). Specifically, a social ecological model suggests that an individual’s behavior is affected by a wide sphere of influences: intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional/organizational/environmental, and public policy (Figure). Intrapersonal factors include such things as cognitive status, physical condition, mood, and underlying diseases such as anemia. Interpersonal interactions are best addressed using the components of social cognitive theory (self-efficacy and outcome expectations) as well as social supports. Environmental issues focus on the physical environment and what is available to facilitate adherence to healthy behaviors. Lastly, organizational, state, and national policy influences health behavior through reward or punishment (eg, insurance costs decreased for healthy behaviors, a fine for not wearing a seat belt).

Intrapersonal Factors

Physiological factors. Serum albumin, particularly a decline in albumin over time,18 osteoporosis,19 D-dimer and inflammatory markers testosterone levels,20 mitochondrial dysfunction,21 and muscle mass changes22 are all associated with weakness and functional decline, and may cause a decrease in willingness to engage in healthy behaviors, particularly with regard to physical activity. Anemia, defined as a hemoglobin of less than 12 g/dL in women and less than 13 g/dL in men,23 has also repeatedly been associated with physical performance, mood, and quality of life,24 and a decline in motivation to engage in health-promoting activities. As with anemia, vitamin D deficiency has been associated with muscle weakness, poor physical performance, balance problems, and falls,25 and thereby can decrease one’s willingness to engage in physical activity.

Normal age changes. Normal age changes associated with smell, taste, hearing, and vision can all influence motivation and adherence to low-fat or low-sodium diets, regular use of health-promoting medications, or physical activity. Older adults’ diminished ability to taste salty and sweet foods over time, for example, makes it particularly difficult for these individuals to adhere to a low-sodium diet or one that eliminates concentrated sweets. Likewise, a hearing impairment that may impact the ability to hear directions regarding a health behavior (eg, instructions during an exercise class) can impact initiation of and adherence to a given recommended behavior.

Psychosocial factors: Mood and fear. The most commonly noted psychosocial factors influencing adherence to healthy behaviors include fear of harm (eg, falling) or exacerbating underlying medical problems (eg, increasing joint pain or shortness of breath), and the influence of mood (either anxiety or depression).26 Repeatedly, fear of falling or exacerbating underlying problems has been associated with reduced time spent in physical activity.27

Depression, which is prevalent among older adults, can also impact individuals’ willingness to engage in any type of health-promoting behavior, such as exercise, eating an appropriate diet, or getting immunizations.28 There may be gender differences in the response to anxiety and depression, and the influence these factors have on adherence to behavior. Both anxiety and depression were significantly associated with physical activity and smoking in males and females, but only associated with diet behavior in men, and only depression was related to smoking in females.29 Overall, depression, rather than anxiety, had a stronger relationship with whether the individual was willing to engage in health promotion behaviors.29 Further, the presence of depression may modulate the relationship between fear and adherence to a health-promoting behavior such as regular physical activity.30

Demographic factors. While not always consistent, there are demographic factors that are associated with adherence to healthy behaviors. Individuals who adhere to such things as physical activity and dietary recommendations tend to be more educated, married, male, and younger.14 In addition, individuals with fewer chronic illnesses are more likely to adhere to health promotion activities across all behaviors.14 Better physical function has likewise been associated with adherence to healthy behaviors such as prophylactic medication use.

Personality, personal preference, and individual factors. Central to motivation and adherence is an individual’s personality and determination to engage in any given behavior. Individuals with a high level of determination, or resilience, have been referred to as the “Super Compliers.”31 Resilience is an individual’s capacity to make a “psycho-social comeback in adversity,”32 and is defined as the ability to achieve, retain, or regain a level of physical or emotional health after illness or loss. Resilient individuals tend to manifest adaptive behavior, especially with regard to social functioning, morale, and somatic health, and are less likely to succumb to illness. Resilience is noted to be related to self-efficacy and outcome expectations, and is a predictor of adherence to regular physical activity among some individuals.33

Interpersonal Factors

Social support. Social support networks including family, friends, peers, and medical professionals, among others, are important determinants of health-promoting behaviors.34 Repeatedly, adherence to regular exercise and heart-healthy diets have been associated with social settings and social supports that encourage these behaviors.31 Social supports are also central to goal identification. For example, being physically strong enough to help a family member with caregiving responsibilities is the type of goal that motivates older individuals to engage in regular exercise.35 Social supports, however, are not always positive or beneficial. Requests to take a spouse or a friend to the doctor may conflict with one’s ability to go to an exercise class. In addition, persistent encouragement from social supports may be interpreted as undesired control or criticism, and thus decrease willingness to change a behavior.

Self-efficacy and outcome expectations. Self-efficacy and outcome expectations are influenced through interactions with others and the environment in which the individual lives. Social-cognitive theory36 proposes that self-efficacy and outcome expectations are the two central concepts to understanding behavior. Specifically, self-efficacy expectations are individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to perform a course of action to attain a desired outcome, and outcome expectations are the beliefs that a certain consequence will be produced by personal action. Efficacy expectations are dynamic and are appraised and enhanced by four mechanisms: (1) enactive mastery experience, or successful performance of the activity of interest; (2) verbal persuasion, or verbal encouragement given by a credible source that the individual is capable of performing the activity of interest; (3) vicarious experience or seeing similar individuals perform a specific activity; and (4) physiological and affective states such as pain, fatigue, or anxiety associated with a given activity.36

Both self-efficacy and outcome expectations play an influential role in the performance of healthy activities, and the adoption and maintenance of regular physical activity. Individuals who are self-efficacious are more likely to initiate behavior change and develop more strategies, effort, and persistence to overcome barriers they encounter when trying to adhere to healthy behaviors. Moreover, individuals with high self-efficacy attribute failure to adhere to healthy behaviors to strategy deficiency rather than a lack of effort or ability.

Bandura37 also describes the importance of self-regulation, which is the personal regulation of goal-directed behavior or performance. This is manifested by goal setting, reinforcements, self-monitoring, corrective self-reactions, and determination to reach desired outcomes. Repeatedly, it has been noted that older adults want assistance from healthcare providers to establish health behavior goals.38 Once goals are established, self-efficacy and outcome expectations play an influential role in the adoption and maintenance of healthy behaviors. Outcome expectations are particularly relevant to older adults.39 These individuals may have high self-efficacy expectations for exercise, for example, but if they do not believe in the outcomes associated with exercise then it is unlikely they will adhere to a regular exercise program. Individuals with strong self-efficacy and outcome expectations to overcome impediments, failures, and setbacks when working toward goal achievement will be more likely to persist with the behavior. Conversely, however, failure to achieve a goal can result in a re-evaluation of the goal, a lowering of self-efficacy, and a decrease in adherence to the behavior of interest.

With age there may be a decrease in exercise self-efficacy and exercise-related outcome expectations40 due to normal age changes (eg, decreased vision and changes in balance), physical health status, as well as individual and cultural beliefs about age and exercise. Conversely, it is possible that with age one has greater expertise in overcoming barriers and adhering in the face of challenges. Moreover, the change in self-efficacy associated with age may be different across different health behaviors.41

Outcome expectations are particularly relevant to older adults. Repeatedly, the benefits or perceived outcomes that the individual associates with adherence to healthy behaviors have been reported to influence behavior.42-44 Some individuals, for example, may have high self-efficacy expectations for exercise, but if they do not believe in the outcomes associated with the behavior (eg, that smoking cessation will improve their current health status), they are less likely to engage in the behavior.

Outcome expectations include both negative and positive aspects across all health behaviors. Older adults may perceive positive benefits associated with exercise, for example, such as increased strength, decreased falls, and improved sense of well-being. Conversely, they may believe that exercise will exacerbate underlying arthritis, cause shortness of breath, or put them at risk for falling.45 Likewise, positive and negative benefits may be associated with adherence to prophylactic medications for stroke prevention or management of heart failure.46 Negative feelings or expectations have also been described as a perceived threat to body sensations, image, self-consistency, and self-ideal.46 These negative outcome expectations were associated with lower adherence to behaviors across exercise, medication, and diet.45,46 Fear of falling or exacerbating pain or comorbid medical conditions and associated symptoms (eg, congestive heart failure, shortness of breath), as noted above, are the most challenging unpleasant sensations associated with engaging in healthy behaviors, particularly exercise.

Environmental Factors

Environments that facilitate healthy behaviors such as physical activity can influence participation in these activities and facilitate long-term adherence.47,48 Unfortunately, such things as accessible and safe walking paths or healthful food options are not always available within a given environment.

Public Policy

Policy initiatives have been successful in changing behaviors in areas such as wearing seat belts.49 While there are some state-based policies associated with smoking behavior and accessibility to calorie, fat, and sodium content in foods, the impact of these policies has not yet been well tested. For some health behaviors such as exercise or prophylactic medication use, there are no national policies. Ongoing research is needed to consider the impact of policies, at the state and national levels, on adherence to healthy behaviors. There is some preliminary evidence to suggest that those who are offered free medical care were more likely to adhere to prophylactic antiplatelet medication use than those who did not have such access to such services.50 It is possible, therefore, that expanded health coverage for all may influence medication adherence in older adults.

New practice guidelines associated with “Welcome to Medicare”51 and Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) programs provide reimbursement and regulatory incentives for providers to take the time to discuss and encourage health promotion activities such as physical activity. The availability of this opportunity should encourage providers and patients to partake of these services.52 It is not known, however, how extensively these guidelines are being utilized in practice.

Interventions to Increase Motivation and Adherence to Healthy Behaviors

Intrapersonal Interventions

Many of the intrapersonal factors influencing health behavior among older adults are not modifiable (eg, demographic variables such as age, gender, and race). Acknowledging these intrapersonal factors, however, serves as a useful reminder to providers to consider the individual differences and preferences that older adults hold with regard to health behavior beliefs. Offering program choices (eg, dance classes, walking classes) may make a major difference in the individual’s willingness to adhere to a positive health behavior.

Optimizing the overall physical condition of the individual should be considered with all older adults and is an important way in which to increase motivation and willingness to engage in healthy behaviors. Specifically, medical management should be implemented for underlying problems such as anemia, vitamin D deficiency, cognitive impairment, comorbid and acute medical problems, and depression.

Interpersonal Interventions

At the interpersonal level, social cognitive theory can be used to guide interventions. Incorporation of enactive mastery experience or helping the individual to successfully perform the activity have included such techniques as breaking down the task into simple steps that could be successfully performed, or starting with an easy-to-perform sitting exercise and increasing the difficulty.53,54

Verbal persuasion, or providing verbal encouragement so that the individual believes that he or she is capable of performing the activity of interest, and setting goals to reinforce that belief and expectation are important motivational interventions.55,56 For individuals who are cognitively impaired and cannot articulate goals, it is useful to review old records and speak with families, friends, and caregivers who have known the individual previously. Goals can then be developed based on their prior life and accomplishments.53,57 To be motivational, goals should be realistic and achievable so as to assure feelings of success.

Also at the interpersonal level, demonstrating caring and confidence in the skills necessary to help the individual (eg, providing assistance with transfers) are central to strengthening the self-efficacy of the individual, and thereby motivating him or her to engage in a specific healthy behavior.58 Another important aspect of caring is setting some guidelines or limits with regard to behaviors. This does not relate to punishment or threats. Rather, it is focused on being firm and informing the individual of the activity he or she needs to do and why he or she needs to do it.

Implementing interventions focused on decreasing unpleasant sensations associated with an activity (eg, pain or anxiety with exercise), or capitalizing on the positive benefits of the activity (improved blood pressure, weight, or blood sugar),59 are effective in strengthening self-efficacy and outcome expectations, and thereby improving adherence to healthy behaviors.60 Interventions to decrease fear are based on cognitive-behavioral therapy and include either graded activity or graded exposure treatment.61-63 Graded activity starts by finding out how much activity the individual can do before pain or fear occurs. The therapist guides the individual in building tolerance to these unpleasant sensations by slowly increasing duration, intensity, and frequency of the exercise or activity that was noted to cause pain.

In contrast, graded exposure treatment involves presenting the participant with anxiety-producing material (eg, having him or her engage in an activity that causes pain) for a long enough time to decrease the intensity of his or her emotional reaction. Ultimately, the feared situation should no longer result in the individual becoming anxious or avoiding the activity.

Other interventions to decrease fear of falling have included exercise activities (walking, strengthening, balance activities, Tai Chi), educational programs, and use of hip protectors.64-66 Outcomes are better when interventions are combined, such as when an educational program is combined with an exercise program.

Exposure to social support networks such as family, friends, peers, and medical professionals are likewise important determinants of healthy behaviors.67 Being told by a healthcare provider to exercise and collaborating on goals has been noted to facilitate behavior change among adults. Among African-American older adults, group-based exercise and diet interventions have been shown to be particularly effective for improving healthy behavior.39,68,69 Social supports are also important sources of goals. For example, being able to walk up stairs to visit grandchildren or being physically strong enough to help a family member are highly motivating goals for some older individuals.35

Environmental Interventions

Examining the environmental setting in which motivational interventions are occurring, although basic, is important to assuring a successful interaction. If the older adult cannot see or hear what a healthcare provider is telling him or her to do, he or she will not perform the activity, and thus will be labeled noncompliant or unmotivated. Simple interventions such as eliminating background noise and speaking slowly, low, and loudly can greatly help these situations.

Environmental interventions include such things as increasing visibility of exercise-related areas, providing walkable spaces, and having interesting walking destinations, all of which are noted to be useful interventions to improve physical activity among older persons.70 Establishing environments in which the individual has easy access to healthful foods and medications at reasonable costs may likewise improve adherence to healthy behaviors. Simple and cost-efficient modifications can be made to the environment to optimize healthy behaviors, such as improving lighting, displaying signs that specifically promote active living in senior housing facilities, for example, and providing physical activity stations throughout a community or housing facility.

Public Policy Interventions

Public health policies can greatly influence adherence to health-promoting activities. Increased access to immunizations against influenza and pneumococcal disease, for example, has improved adherence to immunizations among older adults.71,72 Increased coverage of medication for all Americans through Medicare Part D coverage has increased access for many older adults with regard to prophylactic medication management interventions, such as use of anticoagulants or beta blockers, and thereby has increased adherence for some individuals. Being familiar with policy that supports healthy behaviors is critical, and working to change policy at the local, state, or national level should be part of all health behavior activities.

Conclusion

Motivation to initiate and adhere to healthy behaviors for an older individual involves complex multidimensional factors that must be evaluated on an individual basis. The evaluation should include intrapersonal, interpersonal, environmental, and larger social policy factors, and interventions can then be individualized based on identification of challenges. Assessing motivation and intervening is an ongoing process, and persistence and determination to overcome motivational problems is needed on the part of the healthcare providers. Working together, motivation can be treated and adherence to healthy behaviors improved. In so doing, the individual will be able to obtain and maintain his or her highest level of function and optimal quality of life.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Resnick is Professor, and Sonya Ziporkin Gershowitz Chair in Gerontology, University of Maryland School of Nursing, Baltimore.