A 6-month-old infant was brought for evaluation of an "atypical mole" on the chest that her parents and referring physician feared might be skin cancer. The parents reported that the lesion had been present since shortly after birth and had become red and inflamed after minor trauma on a few occasions and once had blistered.

The infant's medical history was unremarkable; there was no family history of skin disease or skin cancer. She was thriving and otherwise healthy.

A 3-cm, well-defined, tan-to-pink papule was noted on the right anterior chest wall. No blistering or erosion was evident. Gentle stroking of the lesion caused brisk tissue swelling within the papule and a pronounced red flare around it (Darier sign) (Figure 1). The patient had no other lesions, specifically no nevi or café au lait spots. The presumptive diagnosis based on the history and clinical features was solitary mastocytoma.

Figure 1.

The parents were advised to try to protect the lesion from trauma and to expect occasional episodes of swelling or blistering.

SOLITARY MASTOCYTOMA: CAUSE AND PREVALENCEThis uncommon, benign condition is characterized by mast cell hyperplasia and local release of mast cell mediators, such as histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and platelet-activating factor.1 A solitary mastocytoma is the most common of the cutaneous mastocytoses in children.1 It is thought to represent a self-limited reactive process rather than a neoplastic entity.2 The exact cause of cutaneous mastocytosis is unknown.1

A solitary mastocytoma usually is present at birth or develops during early infancy; it is rare in young adults.3 In 55% of patients, onset is before the age of 2 years.1 The condition occurs sporadically, although familial forms have been reported.1 The prevalence is almost equal in both sexes, with a slight predilection for Caucasians.1,4 Neither systemic involvement nor an increased risk of allergies has been reported in children with solitary mastocytomas.1,2

CLINICAL FEATURESSolitary mastocytomas measure 1 to 5 cm.4 They often present on the extremities (Figure 2) and trunk, although the sole, palm, eyelid, and vulva have been involved.3,5 The macule, papule, or nodule may be accompanied by an overlying bulla and later may develop into an infiltrated, rubbery pink, yellow, or tan plaque.3,4 The surface acquires a peau d'orange texture. Hyperpigmentation may be prominent as a result of an overproduction of melanin.2,4 Although solitary mastocytomas are usually asymptomatic, pruritus, generalized flushing, and localized blistering have been reported.1

Figure 2.

DIAGNOSIS

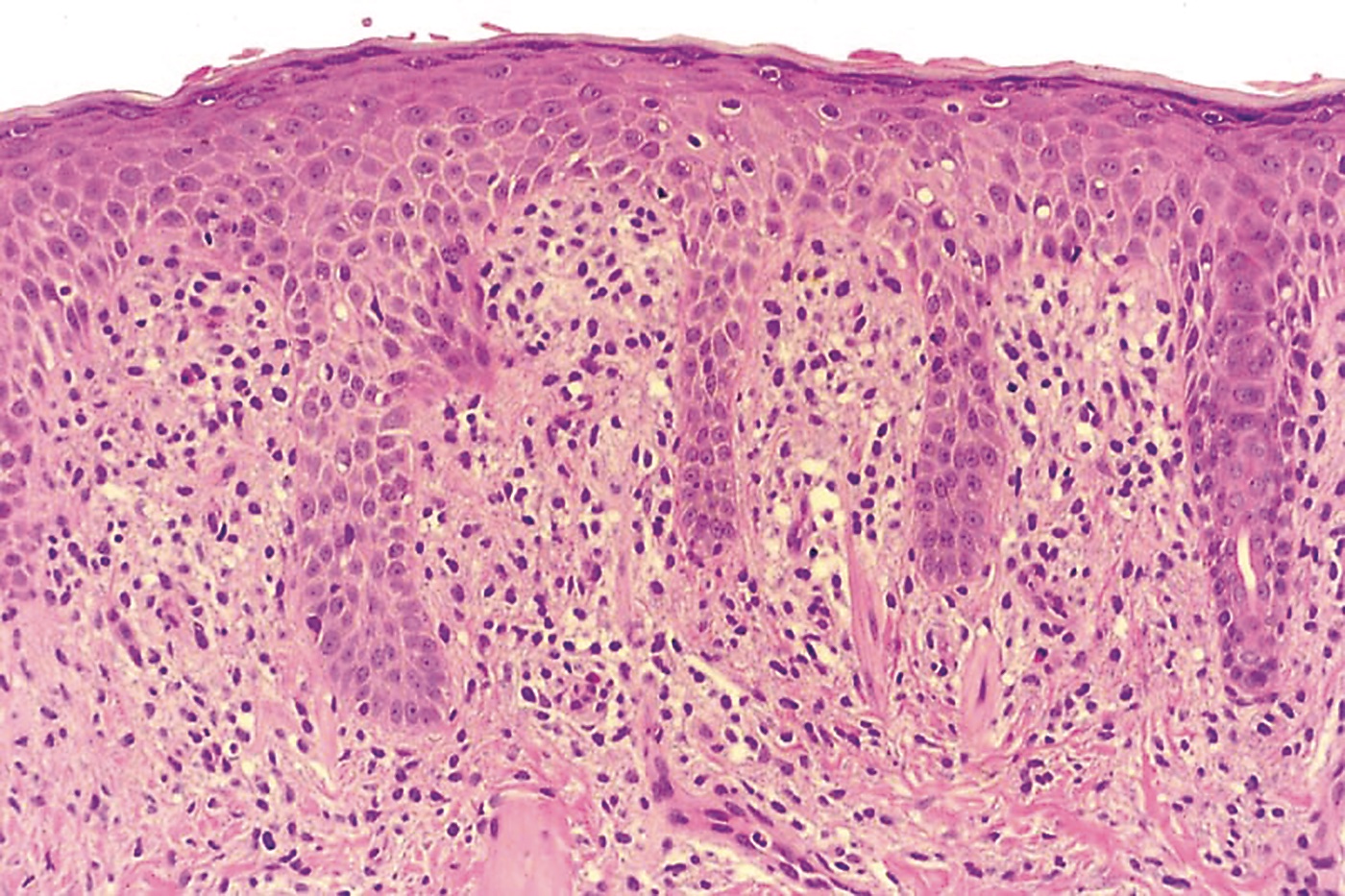

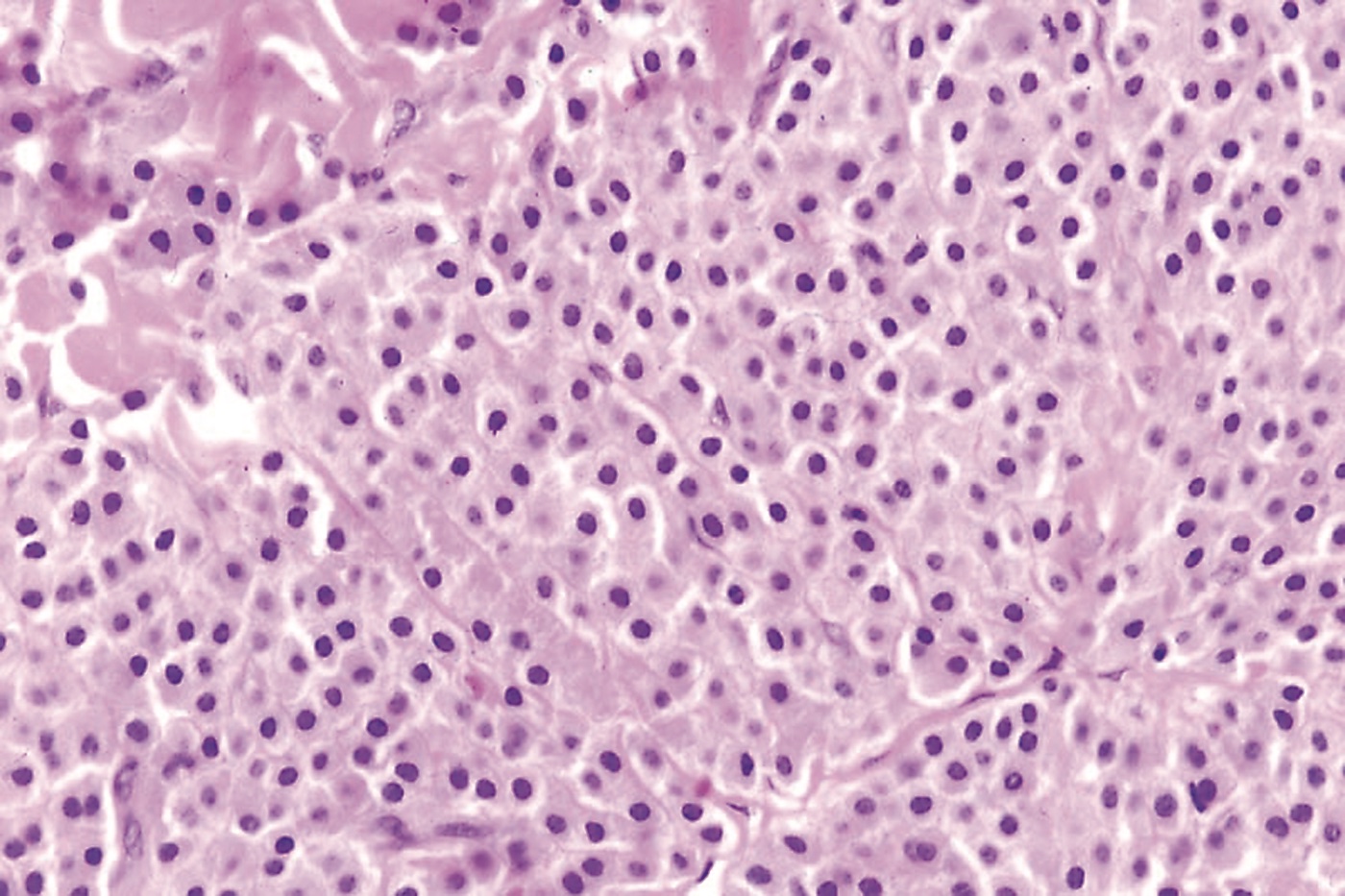

Solitary mastocytoma is usually a clinical diagnosis.4 Episodes of swelling and bulla formation are helpful diagnostic clues.3 The Darier sign is virtually pathognomonic for mastocytoses. Because the disseminated form may begin with a single lesion and dissemination usually occurs within 3 months of onset, the diagnosis of a solitary mastocytoma should not be made unless the single lesion has persisted for more than 3 months.3 Skin biopsy is usually only required in atypical cases.4 Histologically, mastocytomas may show a mast cell infiltrate in the papillary dermis, with variable extension through the reticular dermis and into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 3).3 When the diagnosis is in doubt, consider a referral to a dermatologist.

Figure 3.

TREATMENT

Because solitary mastocytomas usually resolve before adulthood--more than half of cases spontaneously involute by the age of 10 years--treatment is mainly symptomatic.1,3 Avoidance of trauma and direct mast cell degranulators is recommended.6-8 Symptomatic lesions can be surgically excised and usually do not recur.4

Other treatments of solitary mastocytomas have been tried. For instance, tranilast has been shown to prevent swelling.6 Intralesional triamcinolone may reduce pruritus, although it has been associated with cutaneous atrophy.7 Flushing may be prevented by thick layers of hydrocolloid dressings.8