Atypical Fractures Associated With Long-Term Bisphosphonate Use

Seniors are at risk of developing idiopathic osteoporosis and secondary osteoporosis subsequent to various medical conditions, and polypharmacy leaves them susceptible to drug-induced osteoporosis.1 Over the past few years, a number of articles have dealt with the potential risks of long-term bisphosphonate use, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw, atypical femoral fractures, and delayed healing of femoral and distal radius fractures.2-7 In October 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required manufacturers of drugs in this class to add a warning to their labels about the increased risk of two types of atypical femoral fractures with use of these drugs. Patients who experience an atypical femoral fracture while taking bisphosphonates typically present with thigh and/or groin pain.

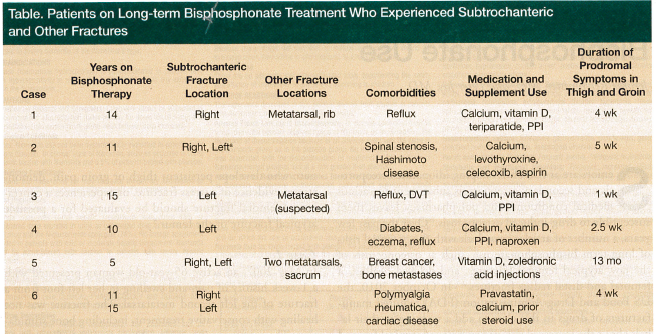

In the past 4 years, our practice has treated six patients who cumulatively sustained eight atypical femoral fractures. All six patients had been receiving long-term bisphosphonate treatment (range, 5-15 years) and some suffered additional fractures before or around the time of the femoral fracture. We recognize that factors other than bisphosphonate use might have contributed significantly to the fracture risk in these six patients, including their activities, cancer history, and medication use.

Although a relationship between long-term bisphosphonate use and increased risk of fracture other than atypical femoral fracture has not been reported and requires further study, we present these cases to alert the medical community of the need to remain vigilant for fractures of bones other than the femur in patients using bisphosphonates long term. We believe these fractures may serve as a harbinger of future fractures, such as fractures of the femur. In addition to a chart review for these patients, we discuss the mechanism of bisphosphonates and the literature surrounding this class of drugs.

Case Studies

We encountered six patients who experienced femoral and other fractures while on long-term bisphosphonate therapy (Table). Studies suggest that anyone taking a bisphosphonate who develops persistent thigh or groin pain, demonstrates evidence of a stress fracture, or experiences a contralateral femoral fracture should be evaluated for a possible atypical fracture of the femur.5

Case 1

In May 2007, an active 65-year-old woman presented with a 1-week history of pain and swelling in her left foot from a fracture of the left second metatarsal. The fracture was not healing with conservative treatment, including bone stimulation. The woman quit smoking 20 years earlier. She started taking alendronate in 1995 and was also taking calcium and etodolac, the latter of which was started several months earlier. Approximately 11 months after the diagnosis, the fracture had still not healed, but she declined further treatment. In March 2010, she suffered an atraumatic rib fracture. In May 2010, she presented with right thigh pain of 1 month’s duration and was limping. At that time, she was using a proton pump inhibitor, was still taking calcium, and said she had been switched to teriparatide 6 months earlier. Plain radiographs showed an impending subtrochanteric fracture, and surgical fixation was performed.

Case 2

In September 2005, a 69-year-old woman presented with a 6- to 7-year history of spinal stenosis and pain in her left leg and buttock that responded to epidural injections. Her medications at that time included alendronate, calcium, aspirin, levothyroxine, and celecoxib. She was asymptomatic until March 2006, when she presented with left groin pain and reported difficulty getting in and out of cars. Radiographs showed subtrochanteric lateral cortex thickening with fracture lines of a transverse type in the left and right femur. Although she recalled twisting and injuring her leg in her basement during the winter, she did not think the current pain was related to that incident. The patient underwent surgical fixation of the left side in March 2006. The right side failed to respond to conservative measures, and 4 months later, she underwent rodding of the right femur.

Case 3

A 72-year-old woman with a 15-year history of alendronate use presented with a 1-month history of right lower back pain and right leg pain, which resolved after she began taking celecoxib. A year before, she experienced left foot pain and was thought to have a metatarsal stress fracture. She then presented with left thigh pain of 1 week’s duration, which worsened while walking. Radiographs revealed typical subcortical thickening on the left femur laterally; a bone scan confirmed a stress fracture. She underwent surgery shortly afterwards.

Case 4

In 2009, a 71-year-old woman with a long history of low back problems and scoliosis presented with left hip, left anterior thigh, and groin pain of 2.5 week’s duration. She had been taking alendronate for more than 10 years. Radiographs revealed typical lateral cortex thickening in the subtrochanteric area. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a bone scan were positive for femoral fracture, which was confirmed with computed tomography scanning. Surgical fixation was performed.

Case 5

A 64-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer and bone metastases was doing well except for experiencing right hip and thigh pain over the past 13 months whenever she performed aerobic exercises. She had been using alendronate for a little longer than 5 years. She underwent MRI, which revealed a subtrochanteric fracture in the typical area. She was treated with a bone stimulator by another orthopedist, but her condition worsened. Additional work-up, including a bone scan, revealed a fractured metatarsal and a fracture in her sacrum. It was determined that these fractures were unrelated to metastatic disease. She underwent intramedullary fixation. An examination 7 months later found questionable fractures in the opposite femur and the second metatarsal of the opposite foot. She did not receive surgical intervention at that time, and when she was last seen in August 2010, the femoral fracture area appeared to be healing.

Case 6

A 68-year-old woman, who had been taking alendronate since 1995, sustained a subtrochanteric fracture in 2006, which was fixed at an outside institution. In subsequent years, she had several other orthopedic problems repaired, including a rotator cuff tear. She presented in the summer of 2010 with multiple problems, and a work-up confirmed that she had polymyalgia rheumatica. She was also experiencing some discomfort in the right sacroiliac joint area and had received 1 month of steroid treatment for hives. In December 2010, she reported a 4-week history of pain in her left thigh. Radiographs confirmed lateral cortex subtrochanteric thickening consistent with a stress facture, which was confirmed with further studies. This fracture was in the same location as the 2006 fracture in the opposite leg. She underwent fixation in December 2010.

Discussion

Bisphosphonates have been shown to increase bone density and decrease the rate of nonvertebral fractures in individuals at risk of osteoporotic fracture. Ideally, patients with an elevated risk of fracture should be identified accurately so that treatment can be targeted appropriately. The FRAX® tool, which the World Health Organization has made available online, is used to assess an individual’s 10-year risk of osteoporotic fracture and can identify patients at increased risk of fracture.8 Bisphosphonate therapy is associated with an increased risk of atypical femoral fractures5 and other adverse events; thus, the need for bisphosphonate therapy should be considered carefully for patients with a low risk of osteoporotic fracture.

Osteoporosis Screening and Treatment

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends using tests such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) of the hip and lumbar spine and quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus to screen all women 65 years and older. Screening is advised for women aged 50 to 65 years who have a 10-year fracture risk equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman with no risk factors (ie, 9.3%), but the USPSTF cautions that other risk factors should be considered when deciding whether screening is appropriate. The USPSTF has stated that there is not enough evidence to determine whether men benefit from osteoporosis screening.9

The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis10 recommends that physicians consider FDA-approved medical therapies for postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or older who have experienced a hip or vertebral fracture or have a T-score of -2.5 or less at the femoral neck or spine, following an evaluation to exclude secondary causes. Physicians should also consider medical therapies for those patients who have low bone mass (ie, a T-score between -1.0 and -2.5 at the femoral neck or spine) and a 10-year probability of a major osteoporosis-related fracture >20% according to the FRAX tool.8,10 When deciding on treatment, the guide also advises taking the clinician’s judgment and patient preferences into consideration.10

Mechanism of Action of Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonate drugs, which have a half-life of more than 10 years, bind to calcium within the bone and inhibit normal bone resorption by the osteoclast.6,11 No enzyme can erode this bond. As bisphosphonates are metabolized, osteoclast function diminishes and the osteoclasts eventually die. As a result, bone resorption—considered a normal part of bone remodeling—decreases.

In general, in vivo studies with animal models and postmortem human studies have shown a decrease in elastic modulus and toughness in bone with accumulation of microdamage from these drugs.12,13 Odvina and colleagues14 have presented studies of transiliac bone biopsies that revealed severe depression of bone formation and minimal identifiable osteoblasts. Due to the cumulative microdamage and lack of effective bone remodeling,15 bone toughness has been estimated to decline by as much as 20% in patients treated with bisphosphonates.16,17

Testing to evaluate the long-term effects of alendronate treatment has been proposed. Tetracycline labeling would be one means of following the effects of long-term alendronate use. Another option would be transiliac crest biopsies.3 However, these tests for bone turnover may be influenced by other factors known to suppress bone turnover. Some follow-up studies show no difference in suppression with alendronate versus suppression from other factors known to affect bone turnover. In randomized trials of bisphosphonates, patients have shown a sustained decrease of 30% to 50% in markers of bone turnover;18 however, no progressive decrease in bone turnover has been observed in patients using these drugs for up to 10 years.19 As these studies demonstrate, there is conflicting information in the literature on bone turnover.

Risk of Atypical Femoral Fractures

It has been hypothesized that the decreased bone toughness observed with bisphosphonate use may lead to bone failure in areas of high tensile strength, such as the subtrochanteric and diaphyseal areas of the femur.16,17 Although the risk of atypical femoral fracture with bisphosphonate use is relatively low, a meta-analysis of three large trials comparing bisphosphonates with placebo found that women taking a bisphosphonate had a reported incidence of subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femoral fractures of 0.8 to 2.4 fractures per 10,000 patients.5 Only a small number of patients in the included randomized trials took bisphosphonates for longer than 4.5 years, however, and it is possible that the fracture incidence would increase with longer use. None of the studies addressed other types of fracture or delayed healing of fractures.

Two Danish studies (N=11,944) concluded that the risk of femoral fracture associated with bisphosphonate use was no greater than the risk of simple osteoporotic fractures.14,16 Critics note that the mean treatment time in these studies was 2.5 years (range, 6 months to 8 years), with only 178 patients having used alendronate for longer than 6 years.16 Femoral fracture risk may be related to concomitant use of medications such as corticosteroids, various hormone replacement therapies, proton pump inhibitors, and other factors.

Radiographic and MRI Appearance of Atypical Femoral Fractures

In patients with an atypical femoral fracture, the subtrochanteric fracture may be transverse or short oblique; the diaphyseal fracture may be a long spiral fracture. Chan and colleagues2 reviewed 34 cases of incomplete and complete fracture and found that all demonstrated focal lateral cortical thickening in the subtrochanteric region. All of the patients had used alendronate for more than 4 years. In patients with incomplete transverse fractures, MRI will typically reveal localized bone marrow edema.

Management of Atypical Femoral Fractures

To reduce the risk of atypical femoral fractures, some physicians have recommended stopping bisphosphonate use in patients who have been taking these drugs for more than 5 years, have stable bone density studies, and have not experienced a fracture.18,20 How long this drug holiday should last has not yet been determined, although 6 to 12 months has been suggested.18,20 Other physicians have recommended switching patients to teriparatide (recombinant–parathyroid hormone), which increases bone turnover.18 Bone density increases have been observed in patients switched from bisphosphonates to teriparatide.18 No data are available, however, on how teriparatide affects atypical femoral fractures. Animal studies appear to show an increased risk of osteosarcoma with teriparatide use, prompting concerns about using this drug beyond 2 years.18 Once patients with oversuppression of bone turnover due to alendronate use have received 2 years of therapy with teriparatide, they should restart antiresorptive therapy (ie, treatment with alendronate).21 Otherwise, the prior increase in bone density will be lost. One challenge is that we do not know how long antiresorptive treatment needs to be continued after being restarted.

When patients with a record of long-term bisphosphonate use present with thigh or groin pain, and subsequent radiography shows lateral cortical thickening confirmed by MRI or a bone scan as an apparent fracture or early stress fracture of the femur,4,22,23 current thinking holds that nonoperative treatment does not work. It is recommended instead that these suspicious femoral areas demonstrating existing or impending fractures be prophylactically nailed.

Conclusion

Although the number of patients in our series is small, we believe these six cases suggest that the appearance of atraumatic fractures or delayed healing of fractures in patients with long-term bisphosphonate use should alert physicians to watch for more serious fractures, such as atypical femoral fractures. More studies are needed, however, that examine the population of patients who have sustained fractures while using bisphosphonates and identify proper management strategies. Until more definitive data are available, healthcare providers should consider the following points:

• Patients at increased risk of osteoporotic fracture, including those with long-term use of corticosteroids, proton pump inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy, should be identified accurately and undergo treatment as appropriate.

• Various tools are available to aid physicians in evaluating patients for osteoporotic fracture risk and the need for treatment and screening, including FRAX8 and the Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis.10

• All women 65 years and older and younger women whose 10-year fracture risk per FRAX is the same as or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors should be screened for osteoporosis (eg, DXA of the hip and lumbar spine and quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus); evidence is insufficient to determine whether men should be screened for osteoporosis.9

• FDA-approved osteoporosis medical therapies should be considered for men and women 50 years or older who have an increased risk of fracture (ie, hip or vertebral fracture, T-score of -2.5 or less at the femoral neck or spine, low bone mass, and a 10-year probability of major osteoporosis-related fracture >20% based on the FRAX tool).10

• Treatment should be given careful consideration for patients at low risk of osteoporotic fracture.

• Primary care physicians should consider a drug holiday for patients who have used bisphosphonates for 5 years.18,20

• When a patient with a history of long-term bisphosphonate use presents with atraumatic fractures or delayed healing of fractures, the physician should monitor the patient closely for serious fractures, such as atypical femoral fractures.

• Patients who have used bisphosphonates long-term, present with thigh pain, and have radiographs demonstrating lateral femoral cortical thickening that is confirmed by MRI or bone scan as an apparent fracture or early stress fracture should have suspicious areas prophylactically nailed.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. O’Connell MB, Borgelt L, Bowles SK, Vondracek SF. Drug-induced osteoporosis in the older adult. Aging Health. 2010;6(4):501-518.

2. Chan SS, Rosenberg ZS, Chan K, Capeci C. Subtrochanteric femoral fractures in patients receiving long-term alendronate therapy: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1581-1586.

3. Odvina CV, Levy S, Rao S, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS. Unusual mid-shaft fractures during long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(2):161-168.

4. Ha YC, Cho MR, Park KH, Kim SY, Koo KH. Is surgery necessary for femoral insufficiency fractures after long-term bisphosphonates therapy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(12):3393-3398.

5. Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, et al; Fracture Intervention Trial Steering Committee; HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial Steering Committee. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(19):1761-1771.

6. Horning JA, Czajka J, Uhl RL. Atypical diaphyseal femur fractures in patients with prolonged administration of bisphosphonate medication of osteoporosis. Orthopedics. 2010;33(12):902-905.

7. Rozental TD, Vazquez MA, Chacko AT, Ayogu N, Bouxsein ML. Comparison of radiographic fracture healing in the distal radius for patients on and off bisphosphonate therapy. J Hand Surg. 2009;34(4):595-602.

8. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. FRAX WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX. Accessed January 13, 2012.

9. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Published January 2011. Accessed January 13, 2012.

10. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2010. www.nof.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/NOF_ClinicianGuide2009_v7.pdf. Published January 2010. Accessed January 13, 2012.

11. Luckman SP, Hughes DE, Coxon FP, Graham R, Russell G, Rogers MJ. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates inhibit the mevalonate pathway and prevent post-translational prenylation of GTP-binding proteins including Ras. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(4):581-589.

12. Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: a register based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(6):1095-1102.

13. Bauer DC, Garnero P, Hochberg MC, et al; the Fracture Intervention Research Group. Pretreatment levels of bone turnover and antifracture efficacy of alendronate; the fraction intervention trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(2):292-299.

14. Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, Maalouf N, Gottschalk FA, Pak CY. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1294-1301.

15. Recker R, Ensrud K, Diem S, et al. Normal bone histomorphometry and 3D microarchitecture after 10 years alendronate treatment of postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(suppl 1):545.

16. Mashiba T, Turner CH, Hirano T, Forwood MR, Johnson CC, Burr DB. Effects of suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates on microdamage accumulation and biomechanical properties in clinically relevant skeletal sites in beagles. Bone. 2001;28(5):524-531.

17. Mashiba T, Hirano T, Turner CH, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB. Suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates increases microdamage accumulation and reduces some biomechanical properties in dog rib. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(4):613-620.

18. Sellmeyer DE. Atypical fractures as a potential complication of long-term bisphosphonate therapy. JAMA. 2010;304(13):1480-1484.

19. Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment; the fracture intervention trial long-term extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927-2938.

20. Seeman E. To stop or not to stop, that is the question. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(2):187-195.

21. Black DM, Bilezikian JP, Ensrud KE, et al; PaTH Study Investigators. One year of alendronate after one year of parathyroid hormone (1-84) for osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(6):555-565.

22. Yoon RS, Beebe K, Benevenia J. Prophylactic bilateral intramedullary femoral nails for bisphosphonate-associated signs of impending subtrochanteric hip fracture. Orthopedics. 2010;33(4):267-270.

23. Capeci CM, Tejwani NC. Bilateral low-energy simultaneous or sequential femoral fractures in patients on long-term alendronate therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):2556-2561.