Aortic Stenosis: A Focused Review on the Elderly

This article is the first in a continuing series on cardiovascular issues in the older adult. The remaining articles in the series, to be published in future issues of the Journal, will discuss such topics as chronic orthostatic hypotension, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, hypertension, and devices for heart rhythm disorders.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Background

Valvular heart disease accounts for 10% to 20% of all cardiac surgical procedures in the United States, and two-thirds of all heart valve operations are aortic valve replacements.1 Aortic valve disease is the most common valve disease in adults over 60 years of age.2 There are two types of aortic valve disease: aortic regurgitation and aortic stenosis (AS). The focus of this article is AS, which is a progressive, slow disease process that can take several years to manifest symptoms. It may be congenital or acquired. In patients with AS, the opening of their aortic valves are narrowed, which decreases blood flow from the heart. Although the top two causes of AS are calcification of normal trileaflet aortic valve (formerly termed senile or degenerative calcification) and calcification of congenital bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), there is growing evidence suggesting that the disease process is the same regardless of the type of calcification. Calcified aortic valve disease (CAVD) is the preferred terminology for AS, regardless of whether 2 or 3 leaflet valves are calcified.2 The spectrum of CAVD ranges from mild sclerosis to severe stenosis. Aortic valve sclerosis is the thickening of the valve leaflets without restriction of leaflet excursion and obstruction of blood flow. Unlike stenosis, aortic sclerosis does not involve the fusion of the valve commissures.

Although it is associated with increasing age, AS is not a normal aging process. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, AS was present in 2% of the entire study cohort (adults ≥65 years), 2.6% of those 75 years or older, and 4% of those 85 years or older. Aortic sclerosis was present in 26% of the entire study cohort (adults ≥65 years) and 37% of persons age 75 years or older.3 The prevalence of AS was twofold higher in men, and no racial predilection was noted.3 Other risk factors for the development of AS include elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and lipoprotein(a) levels, diabetes, smoking, and hypertension.

Pathogenesis

The current concept of CAVD progression involves lipid deposition, inflammation, and calcification. The accumulation of oxidized LDL particles, along with the production of angiotensin II and inflammation from T lymphocytes and macrophages, are the hallmarks of lesions involved in early aortic valve stenosis. The end result of this process is the development of a lesion consisting of calcium nodule and bone formation on the valve leaflets; a similar process is seen in vascular calcification occurring elsewhere in the body. The progressive calcification in AS starts along the flexion lines at the bases of individual leaflets, which eventually leads to immobilization of the cusps (Figure).4 All leaflets are involved in this process, regardless of bileaflet or trileaflet aortic valve calcification.

Local and systemic handling of calcium metabolism and genetic mutation are also being studied in the pathogenesis of AS.5,6 For example, there is a higher prevalence of CAVD in patients with end-stage renal disease, Paget’s disease of bone, and hyperparathyroidism. In addition, mutations in NOTCH1, a signaling and transcriptional regulator, are associated with BAV and severe aortic calcifications.

BAV is another common cause of AS. It is the most common congenital heart defect, occurring in 1% to 2% of live births.2 In a study of 932 aortic valves removed because of AS, the frequency of BAV was 49% (n = 458).7 Although BAV is associated with a younger age group, approximately 40% of patients over 70 years who had aortic valve replacement for isolated AS had BAV.7

Rheumatic aortic valve disease, although uncommon in the developed world, remains a major cause of AS worldwide. Although rheumatic heart disease affects mainly the mitral valve, it can also be seen in one-third of patients with aortic valve disease.1 Of note, rheumatic aortic valve disease in isolation without mitral valve involvement is extremely rare.

Presentation

The diagnosis of AS often begins with the discovery of a systolic murmur on physical examination and is confirmed by echocardiography. The murmur is best heard at the right upper sternal border second intercostal space in a crescendo-decrescendo pattern with radiation to the carotids. The S2 is usually diminished and the carotid pulse is delayed. As the AS becomes severe, the S2 becomes absent and the carotid pulse becomes smaller in intensity and delayed (“pulses parvus et tardus”). The intensity of S2 is a very reliable marker of the severity of AS. The softer the S2 sound, the more severe the AS. Another finding in severe AS is a reduced systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure. AS is often mistaken for mitral regurgitation; however, performing a few quick maneuvers can distinguish the two murmurs. For example, squatting increases AS murmur while the Valsalva maneuver or standing from a seated position decreases AS murmur.

Patients with AS classically present with four symptoms: dyspnea; angina pectoris; syncope; and heart failure. Symptoms typically start at age 50 to 70 years in those with BAV, and at approximately 70 years for those with calcified trileaflet aortic valve.1 Dyspnea and decreased exercise tolerance are usually the first symptoms of AS. The mechanism of these symptoms is secondary to abnormal diastolic dysfunction and low cardiac output. The stenotic aortic valve causes increased resistance for the left ventricle (LV), which eventually translates into increases in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure over time (ie, abnormal diastolic dysfunction). In addition, the resistance of the AS also causes the LV to fail and unable to maintain cardiac output with increasing demand, such as that occurring during exercise.

Two-thirds of patients with severe AS with and without coronary artery disease present with angina.1 This symptom is often precipitated by exertion and relieved with rest, similar to angina from coronary artery disease. Angina of AS occurs due to a combination of increased oxygen needs of hypertrophied myocardium and reduced oxygen delivery.

Syncope results from decreased cerebral perfusion during exertion. Arrhythmias are a rare cause of syncope of AS, unless the left ventricular function is depressed. Another mechanism of syncope of AS is believed to involve abnormal LV baroreceptor function and excessive vasodilation from increased LV systolic pressure during exertion.

Heart failure from severe AS is a result of both diastolic and systolic dysfunction. Diastolic dysfunction is caused by elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, and systolic dysfunction (ie, depressed ejection fraction) is a result of chronic afterload mismatch imposed by the obstructive valve.

Other conditions associated with severe AS include anemia and conduction disease. Anemia occurs as a result of gastrointestinal bleeding from angiodysplasia often in the right colon (Heyde’s syndrome). The tight aortic valve causes shear stress-induced platelet aggregation, which results in a reduction of von Willebrand factor. Often, the angiodysplasia is reversed after aortic valve replacement. Conduction disease associated with severe AS can occur due to aortic valve annular calcification extension into the atrioventricular node (Lev’s disease) and coexisting degenerative changes.

Diagnosis

Transthoracic echocardiography is one of the most useful tools to diagnose AS. Echocardiography provides visualization of the severity of valve calcification, orifice area, and assessment of other structures (LV size, aortic root, mitral valve) needed to determine prognosis and treatment. Doppler velocities can also be obtained to confirm and monitor the disease progression. The accuracy of current echocardiography technology to diagnose severe AS has made invasive testing by cardiac catheterization unnecessary. Additional imaging modalities such as transesophageal echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can provide some additional information on the patient’s condition, particularly when the imaging windows seen on transthoracic echocardiography are suboptimal due to body habitus. Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, and European Association of Echocardiography no longer recommend routine hemodynamic catheterization for assessment of severity of AS in patients who are symptomatic, unless noninvasive testing is nondiagnostic or there is a discrepancy between the findings from noninvasive testing and the clinical findings.4,8

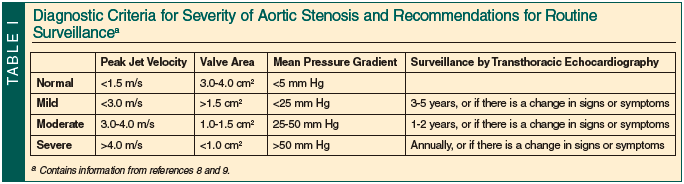

Although many diagnostic criteria for AS severity exist, three recommended parameters include calculated valve area, mean pressure gradient, and peak jet velocity.4 Routine surveillance of asymptomatic AS by echocardiography depends on the severity of the stenosis. Reevaluation should be performed annually for severe AS, every 1 to 2 years for moderate AS, and every 3 to 5 years for mild AS. Reevaluation should also be considered when there is a change in signs or symptoms (Table I).8,9

Prognosis and Progression

The prognosis of severe untreated AS is extremely grim. As compared with asymptomatic AS, the mortality associated with symptomatic AS is very high. From the onset of symptoms to the time of death is approximately 5 years for those presenting with angina, 3 years for those with syncope, and 2 years for those with heart failure.10 The risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality in patients older than 65 years with a diagnosis of CAVD is 50% higher than in patients with normal aortic valves.11 Although the progression from valve sclerosis to stenosis is approximately 5% over a 10-year period, the progression from mild to severe stenosis can be rapid once stenosis develops. On average, the mean pressure gradient of the valve stenosis progresses 6 to 7 mm Hg per year and the valve area decreases by 0.1 cm² per year.12 Severe AS can remain asymptomatic for many years; however, after symptoms develop, the overall mortality is high, with an average survival of only 2 to 3 years.8

Management

Medical management of AS with statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors has not shown any benefit in the improvement of survival. The Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial enrolled 1873 patients to evaluate AS progression with statin use. After a follow-up of approximately 52 months, researchers found no difference in the progression of AS or in the rate of aortic valve replacement.13

Surgical repair of AS is the standard of care. Due to the natural history of AS, the question regarding aortic valve replacement is not whether to replace the valve but when to replace it. Timing is crucial in aortic valve replacement. Currently, guidelines recommend aortic valve replacement in symptomatic patients with severe AS, patients with severe AS undergoing other cardiac surgery (eg, coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]), or asymptomatic patients with severe AS with decreased ejection fraction (Table II).8 Other common indications for surgery include asymptomatic patients with severe AS in whom symptoms are provoked with an exercise stress test or patients who have moderate AS who are undergoing other cardiac surgery (eg, CABG, ascending aortic surgery, or other valve surgery).

Asymptomatic patients should also be counseled on the high likelihood of needing surgery within 5 to 10 years once they develop moderate-to-severe AS. Counseling should include a discussion of the risk of the operative mortality and morbidity. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons database estimates that the operative mortality risk of aortic valve replacement alone is 3.2% and aortic valve replacement with CABG is 5.6%.14

Although increasing age presents a higher operative risk in patients with AS, the overall risk when adjusted for comorbidities is similar to that of the general population. The rate of survival after the valve replacement indicates survival benefit.15 Advanced age should not be considered a contraindication for aortic valve replacement in those individuals who would otherwise meet the criteria for surgery. High-functioning elderly patients with relatively few comorbidities do well with aortic valve surgery, experiencing substantial benefits from it, including symptom relief, longevity, and improved quality of life. Patients who survive the first 30 days after the aortic valve surgery have an overall survival rate similar to age-matched cohorts.15 The left ventricular systolic and diastolic function improves significantly after surgery. Furthermore, most patients have a resolution of their pre-AS symptoms after aortic valve replacement.

In a select patient population in whom the risk of conventional surgery is deemed too high, other methods such as balloon valvuloplasty and percutaneous aortic valve replacement are an option. These procedures carry their own inherent risks. Balloon valvuloplasty has the complications of embolic stroke and myocardial infarction, and the rate of valve restenosis is 6 to 12 months.8 Percutaneous aortic valve replacement offers promising results for very high-risk patient populations. The procedure is less invasive, involving the deployment of a replacement aortic valve using catheters via the femoral artery or transapical approach using minimal incision in the left axilla. In the recent Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve (PARTNER) trial, the rate of death from any cause at 1 year was 30.7% in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement group as compared with 50.7% in the standard therapy group.16

Conclusion

AS comprises a major proportion of valvular heart disease in the United States. The natural history of the disease process results in high morbidity and mortality once severe AS develops. Advances in molecular biology and genetics have improved our understanding of the disease process. As such, AS is no longer considered a “normal” aging process. With an estimated 4% incidence in those 85 years of age or older, the overall prevalence and burden of disease will increase as the population continues to live longer. Patients with AS must have close monitoring of symptoms. Once severe AS develops, the overarching principle of treatment is not whether to replace the valve, but rather when to replace the valve. Advanced age should not be a deterrent to surgical repair. Recent improvements in surgical techniques by both open thoracotomy and percutaneous valve replacement have resulted in significant symptom relief and a decline in mortality, even in octogenarians.16

Dr. Gongidi is Cardiology Fellow, and Dr. Hamaty is Clinical Assistant Professor and Program Director, Cardiology Fellowship, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey School of Osteopathic Medicine, Stratford.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank David Dinan, MD, for his helpful critiques and editorial assistance. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Otto CM, Bonow RO. Valvular heart disease. Braunwald’s Heart Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008:1625-1692.

2. Kurtz CE, Otto CM. Aortic stenosis: clinical aspects of diagnosis and management, with 10 illustrative case reports from a 25-year experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89(6):349-379.

3. Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(3):630-634.

4. Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, et al; American Society of Echocardiography; European Association of Echocardiography. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice [published correction appears in J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(5):442]. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(1):1-23.

5. Ortlepp JR, Hoffmann R, Ohme F, Lauscher J, Bleckmann F, Hanrath P. The vitamin D receptor genotype predisposes to the development of calcific aortic valve stenosis. Heart. 2001;85(6):635-638.

6. McKellar SH, Tester DJ, Yagubyan M, Majumdar R, Ackerman MJ, Sundt TM 3rd. Novel NOTCH1 mutations in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease and thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):290-296.

7. Roberts WC, Ko JM. Frequency by decades of unicuspid, bicuspid, and tricuspid aortic valves in adults having isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, with or without associated aortic regurgitation. Circulation. 2005;111(7):920-925.

8. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al; 2006 Writing Committee Members; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2008;118(15):e523-e661.

9. Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, et al; Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(2):230-268.

10. Rosenhek R, Binder T, Porenta G, et al. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(9):611-617.

11. Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, Gersh BJ, Siscovick DS. Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):142-147.

12. Otto CM, Burwash IG, Legget ME, et al. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Clinical, echocardiographic, and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation. 1997;95(9):2262-2270.

13. Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, et al; SEAS Investigators. Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1343-1356.

14. O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, Filardo G, et al; Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 2—isolated valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1 suppl):S23-S42.

15. Kvidal P, Bergström R, Hörte LG, Ståhle E. Observed and relative survival after aortic valve surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(3):747-756.

16. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-1607.