Addressing the Needs of Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adults

Case Vignette

A 66-year-old man presents to his new primary care physician for the first time with reports of chronic pain, anxiety, panic attacks, and poor concentration; upon further questioning from the physician, the patient also reports sexual dysfunction. His medical history is significant for hypertension, depression, and possibly alcohol abuse. The patient has never been married, has no children, and lives with a male roommate who accompanies him to the visit. Due to the patient’s anxiety and poor concentration, the roommate provides much of the patient’s information, including intimate details of the patient’s medical history. The primary care physician suspects that the two men are in a relationship, and despite asking open-ended, nonjudgmental, gender-neutral, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)–affirming questions, the patient avoids answering any inquiries that might reveal his sexual orientation. He also refuses to give his physician any additional details about his social history that are necessary to address his concerns about his anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction.

Is it important for healthcare providers to know the sexual orientation of their older patients? Are there specific issues that need to be addressed differently in older LGBT adults? How does one inquire into the sexual and social history of an older adult?

Introduction

Older adults who are LGBT are a vulnerable group with specific healthcare needs that are largely unrecognized by healthcare professionals. LGBT populations have higher rates of common and life-threatening physical and mental health conditions. Unfortunately, very little research and education has focused on the healthcare needs of older LGBT adults, and how they differ from their aging heterosexual peers or from the younger LGBT population. LGBT Americans are recognized by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services as 1 of 6 groups affected by health disparities.1,2 In its document “Healthy People 2010,” a 10-year plan to eliminate health disparities among different segments of the population, sexual orientation was included in 29 specific objectives.2 The recently released “Healthy People 2020” continues to address the health disparities of LGBT individuals, which are linked to societal stigma, discrimination, and denial of their civil and human rights.3 The report states that discrimination against LGBT persons has been associated with high rates of psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and suicide. In addition, there are long-lasting effects on the individual and the community from frequent experiences of violence and victimization, as well as struggling with issues of acceptance (personal, family, and societal).3

In this review article, we will explore the important issues that are unique to the older LGBT adult, including the coming-out experience, medical and psychological concerns, feelings of invisibility and isolation, lack of social supports, and discrimination. We will also address the importance of healthcare providers being aware of their older patients’ sexual orientation to improve patient care, change communication techniques, and improve health outcomes. We searched MEDLINE to identify recent scientific articles, and we reviewed practice guidelines and primary care textbooks to gather information.

Background

Definitions

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual are terms used to describe a person’s sexual orientation, which describes orientation toward people of the same gender in sexual behavior, attraction, and/or self-identification (Table I).4 It is important to note that sexual orientation is much more than sexual behavior. One can have same-sex relations without identifying as homosexual, and, conversely, one can have same-sex attraction without engaging in homosexual behavior or identifying as homosexual. Transgender refers to the broad category of people whose gender identity and expression do not match, including transsexuals (those who identify as, or desire to be, a gender different from what was assigned at birth, and may undergo gender transition) and transvestites (those who cross-dress).4 Gender has a strong cultural definition, in addition to precise biological and extensive psychosocial components.4 While gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation, there are shared experiences of stigma and other social and cultural factors that link issues of transgender persons to those of lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons.

Demographics

It is difficult to know how many LGBT people over the age of 65 there are, due to lack of data, differing estimates by experts in related fields, and stigma that causes the underidentification and undercounting of older LGBT people. Most sources estimate that there are between 1 million and 3 million older LGBT Americans, and by 2030, there will be an estimated 2 million to 6 million older LGBT adults in the United States.5,6 Unfortunately, there are no reliable data available on the numbers of elderly transgender people. U.S. census data from 2000 showed that same-sex–headed households existed in 93% of all counties, and that more than 1 in 10 same-sex couples included a partner older than age 65.7 LGBT elderly persons are more likely to live alone and less likely to be living with a partner as compared with heterosexual elderly persons.8,9 A New York City survey from 1999 showed that 65% of LGBT elderly persons were living alone, which was twice the rate for that of heterosexual older adults.8 Additionally, less than 20% of older LGBT adults were living with a life partner as compared with 50% of heterosexual seniors.

Coming Out  While all older LGBT adults came of age during a time in the United States when being LGBT was viewed in an especially negative light, this group is divided into two cohorts, depending on whether they came of age before or after the Stonewall Riots of 1969. The Stonewall Riots were demonstrations of protest against a police raid that targeted the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City, because it was a bar frequented by LGBT persons. The Stonewall Riots are often considered the beginning of the gay civil rights movement. It was not until the 1970s that society’s view of homosexuality began to change, and the current older, pre-Stonewall generation grew up in a society with widespread discrimination against LGBT persons. The pre-Stonewall generation lived most of their lives in a society where the expression of their sexual orientation was criminalized by the government and pathologized by the medical community. This elderly generation of LGBT persons is much more likely to keep their sexual orientation hidden. In contrast to the pre-Stonewall generation, the Stonewall generation of LGBT baby boomers, those currently in their 50s or 60s, came of age during the social unrest of the 1960s, a time of rising social acceptance of LGBT people. LGBT baby boomers are more likely to be at least partly open about their sexual orientation (ie, open to certain people but perhaps not to others). This younger cohort participated in or benefited from the activism and advocacy of the gay civil rights movement, and were also greatly impacted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic and activism of the 1980s.10 For example, a marketing survey of 1000 LGBT people in the baby boomer generation conducted by the LGBT Aging Issues Network (LAIN) of the American Society on Aging, MetLife Mature Market Institute, and Zogby International indicated that 44% of subjects were “completely out” and that another 31.7% were “mostly out.”11

While all older LGBT adults came of age during a time in the United States when being LGBT was viewed in an especially negative light, this group is divided into two cohorts, depending on whether they came of age before or after the Stonewall Riots of 1969. The Stonewall Riots were demonstrations of protest against a police raid that targeted the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City, because it was a bar frequented by LGBT persons. The Stonewall Riots are often considered the beginning of the gay civil rights movement. It was not until the 1970s that society’s view of homosexuality began to change, and the current older, pre-Stonewall generation grew up in a society with widespread discrimination against LGBT persons. The pre-Stonewall generation lived most of their lives in a society where the expression of their sexual orientation was criminalized by the government and pathologized by the medical community. This elderly generation of LGBT persons is much more likely to keep their sexual orientation hidden. In contrast to the pre-Stonewall generation, the Stonewall generation of LGBT baby boomers, those currently in their 50s or 60s, came of age during the social unrest of the 1960s, a time of rising social acceptance of LGBT people. LGBT baby boomers are more likely to be at least partly open about their sexual orientation (ie, open to certain people but perhaps not to others). This younger cohort participated in or benefited from the activism and advocacy of the gay civil rights movement, and were also greatly impacted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic and activism of the 1980s.10 For example, a marketing survey of 1000 LGBT people in the baby boomer generation conducted by the LGBT Aging Issues Network (LAIN) of the American Society on Aging, MetLife Mature Market Institute, and Zogby International indicated that 44% of subjects were “completely out” and that another 31.7% were “mostly out.”11

Communication

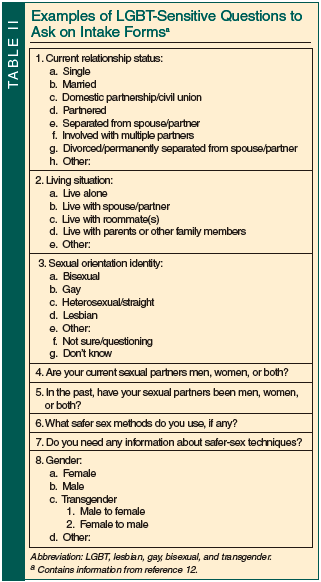

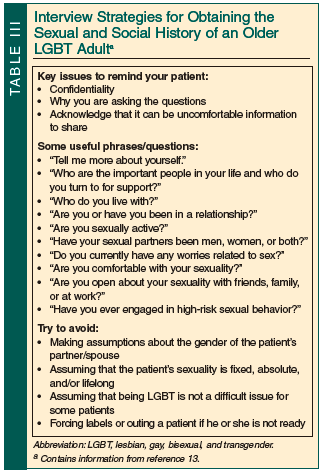

Healthcare providers should provide culturally competent care that creates the optimal environment for the respectful care of older LGBT adults. All healthcare providers should ask their older patients about their sexual health, including sexual orientation. Keep in mind that older LGBT adults may be unwilling or psychologically unable to disclose their sexual orientation, even if asked directly. In its “Guidelines for the Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients,” the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association offers tips on how to create a welcoming practice environment and recommends strategies for intake forms and questioning that do not presume heterosexuality and that allow for open and comfortable discussion (Table II).12 Interview strategies for obtaining the sexual and social history of older LGBT adults are available in Table III.1

Healthcare providers should provide culturally competent care that creates the optimal environment for the respectful care of older LGBT adults. All healthcare providers should ask their older patients about their sexual health, including sexual orientation. Keep in mind that older LGBT adults may be unwilling or psychologically unable to disclose their sexual orientation, even if asked directly. In its “Guidelines for the Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients,” the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association offers tips on how to create a welcoming practice environment and recommends strategies for intake forms and questioning that do not presume heterosexuality and that allow for open and comfortable discussion (Table II).12 Interview strategies for obtaining the sexual and social history of older LGBT adults are available in Table III.1

Healthcare Disparities

In a landmark decision by the American Psychiatric Association in 1973, same-sex orientation was redefined as a normal sexual variant rather than a psychiatric disorder.14 While this ended an era of treating homosexuality as a pathologic condition, it was noted decades later that discrimination still exists in the medical community.15-18 A survey published in 2002 of practicing physicians found that only 73% reported feeling “very comfortable” taking care of an openly gay or lesbian patient.16 A survey of New York Area Agencies on Aging in 1994 surprisingly showed that 46% of agencies would not welcome LGBT seniors into their facilities.18 While this study is being updated,17 and much has changed in both the medical community and in society in general since its publication, there is still a need for better education and a reduction of the barriers to care.1

Older LGBT adults may have barriers to receiving appropriate healthcare as a result of their current or past negative experiences with the medical profession because of their sexual orientation. A report published in 1999 by the Institute of Medicine sought to examine this issue and encouraged research into the barriers specifically faced by lesbians.19 An example of one of these barriers was discussed in another study published the same year, which found that poor relationships with providers and mistrust of others in the medical field were some of the reasons why older lesbians appeared to have lower rates of mammography screening.20 This sentiment was also demonstrated in the aforementioned LAIN survey of LGBT baby boomers, where less than half expressed strong confidence that healthcare professionals would treat them with dignity and respect because of their sexual orientation.11 These findings are discouraging because access to healthcare and receipt of appropriate care require an open and trusting doctor-patient relationship.

Specific Medical Issues

Older LGBT adults can have the same geriatric syndromes as their heterosexual counterparts, and need much of the same health promotion and maintenance; however, there are certain medical issues that require particular attention in older LGBT adults. (Table IV provides an overview of specific healthcare issues to address in older LGBT adults, to be further discussed in this section.) The specific medical issues faced by older gay and bisexual men, lesbians and bisexual women, and transgender adults will be reviewed separately, followed by a review of the sexual health, mental health, and psychosocial issues impacting the entire older LGBT population.

Care of Older Gay and Bisexual Men

Sexually active gay and bisexual men who have sex with multiple partners should be routinely screened for HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, herpes, and human papillomavirus (HPV), and also receive vaccinations for hepatitis A and B.10 Many experts agree that men who engage in receptive anal sex should have anal Pap smears every 2 to 3 years, as HPV can lead to anal lesions and squamous cell carcinoma,10,21 while HIV-infected individuals should be screened annually.22

Men who have sex with men may be at higher risk for certain cancers. As previously mentioned, anal HPV infection can lead to anal intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. The incidence of anal cancer is 43 times more common in HIV-negative gay men than in HIV-negative heterosexual men (35/100,000 vs 0.8/100,000), and 88 times more common in HIV-positive gay men (70/100,000).10 The risks of other cancers related to both HIV/AIDS infection (eg, Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphoma) and higher rates of smoking (lung cancer) in men who have sex with men are also important to note. (Additional information about HIV/AIDS is provided in the “Sexual Health” section.) In addition, prostate cancer and its treatment can have profound social, emotional, and sexual function effects that are unique to men who have sex with men.23 For example, a gay patient may be concerned about how the removal of the prostate could affect sexual response during anal sex.10

While younger gay men are significantly more likely to smoke,4 the prevalence of smoking in older gay men is unknown, although the health effects naturally carry over. Data about whether alcohol and other drug use in the general gay and bisexual male population are different from the general male population are conflicting,4 and data on older LGBT men are lacking. Information on mental health issues in gay and bisexual men is included in the “Mental Health Issues” section. (See Table V for a list of 10 issues to address with gay and bisexual men.21)

While younger gay men are significantly more likely to smoke,4 the prevalence of smoking in older gay men is unknown, although the health effects naturally carry over. Data about whether alcohol and other drug use in the general gay and bisexual male population are different from the general male population are conflicting,4 and data on older LGBT men are lacking. Information on mental health issues in gay and bisexual men is included in the “Mental Health Issues” section. (See Table V for a list of 10 issues to address with gay and bisexual men.21)

Care of Older Lesbians and Bisexual Women

There is good evidence that lesbians and bisexual women are less likely to receive appropriate preventive care, access healthcare services less often, and enter the healthcare system later than heterosexual women.10,24 These discrepancies are due to barriers such as inappropriate testing and assumptions of heterosexuality by the healthcare provider, or possibly due to the patient’s fear of discrimination. Lesbians and bisexual women appear to be at greater risk of cardiovascular disease due to higher rates of obesity, metabolic syndrome, smoking, and alcohol use.24 Lesbians may also be at higher risk of breast and cervical cancer due to lower rates of mammography screening and Pap smear testing, less gynecologic care, and higher rates of smoking and alcohol use.24 Nulliparity is also a risk factor for ovarian cancer and breast cancer, although it must not be assumed that a lesbian or bisexual woman is nulliparous. Higher rates of smoking in lesbians and bisexual women also increase the risk of lung cancer, osteoporosis, and other associated illnesses.10

While sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) including HIV occur less frequently in women who have sex with women as compared to heterosexual women, women who have sex with women are still at risk for transmitting HPV, bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, and trichomonas during sexual activity. Of note, a high percentage of lesbians (70%) also report having sex with men at some point in their lives, which underscores the importance of routine age-appropriate STD screening, including Pap smears.9

Lesbians and bisexual women are twice as likely to be heavy smokers as heterosexual women.24 Similar to gay and bisexual men, data on the rates of alcohol and other substance use in lesbians and bisexual women are conflicting,4 and data in older LGBT women are lacking. Information on mental health issues in lesbians and bisexual women is included in the “Mental Health Issues” section. (See Table VI for a list of 10 issues to address with lesbian and bisexual women.25)

Lesbians and bisexual women are twice as likely to be heavy smokers as heterosexual women.24 Similar to gay and bisexual men, data on the rates of alcohol and other substance use in lesbians and bisexual women are conflicting,4 and data in older LGBT women are lacking. Information on mental health issues in lesbians and bisexual women is included in the “Mental Health Issues” section. (See Table VI for a list of 10 issues to address with lesbian and bisexual women.25)

Care of Older Transgender Adults

Very little research exists on the care of transgender older adults. The care of these patients is complex, and a full review is beyond the scope of this article. (See Table VII for resources for additional information about the care of transgender patients.10) One caveat that is notable in the care of older transgender adults is that since few undergo sex reassignment surgery, preventive care should include care for the biological sex (for example, prostate cancer screening in a woman who transitioned from a man, and ovarian cancer screening in a man who transitioned from a woman).

Transgender adults are much more likely than other sexual minorities to face widespread discrimination and multiple barriers to obtaining appropriate care. Many insurance companies explicitly exclude coverage for transgender care, unless the patient has the stigmatizing diagnosis of gender identity disorder. Gender identity disorder is a diagnosis included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), which labels gender identity differences as a mental illness.26 Without insurance coverage for gender transitioning surgery or medication, transgender persons are more likely to use black-market hormones or injectable silicones. Transgender people are also more likely to be unemployed or underemployed, or do not seek care due to past traumatic experiences, and therefore receive less preventive care, and are less likely to have their mental health needs met.10 (Additional information about  the mental health of transgender persons is included in the “Mental Health Issues” section.) Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use are more common in this population. There are also higher rates of HIV and hepatitis C due to the higher prevalence of shared needles for hormones, as well as other high-risk sexual behaviors.10 While a full review of the healthcare needs of transgender persons is beyond the scope of this article, it is clear that older transgender patients face unique health issues. As they age, they are more likely to encounter health issues related to their biological sex, which can cause additional stress in coping with a disease associated with a gender they no longer identify with.10 (See Table VIII for a list of 10 issues to address with transgender patients.27)

the mental health of transgender persons is included in the “Mental Health Issues” section.) Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use are more common in this population. There are also higher rates of HIV and hepatitis C due to the higher prevalence of shared needles for hormones, as well as other high-risk sexual behaviors.10 While a full review of the healthcare needs of transgender persons is beyond the scope of this article, it is clear that older transgender patients face unique health issues. As they age, they are more likely to encounter health issues related to their biological sex, which can cause additional stress in coping with a disease associated with a gender they no longer identify with.10 (See Table VIII for a list of 10 issues to address with transgender patients.27)

Sexual Health

The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in older adults continues to increase and is of particular importance in the LGBT population. In 2005, nearly 25% of all persons living with HIV/AIDS were older (≥ 50 years), and by 2015, half of the HIV-positive population will be over age 50.28 The number of older adults with HIV/AIDS is increasing partly due to greater longevity resulting from improved treatment, but also from a rise in new HIV diagnoses in older adults. In 2005 15% of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses were in older adults.28 In 2008, 53% of new HIV infections occurred in men who had sex with men.29 Unfortunately, the clinical suspicion of HIV/AIDS in older adults is often too low, leading to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. A 2007 study of over 8000 patients from 6 Veterans Affairs healthcare systems found the rates of undocumented HIV infection in outpatients to be 0.7% in those age 55 to 64, 0.5% in those age 65 to 74, and 0.1% in those older than age 75.30 Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends routine HIV screening for all persons age 13 to 64,31 routine screening in some sexually active adults age 55 to 75 has also been shown to be cost-effective,32 highlighting the need for continued HIV and sexual health screening in older adults.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is the mainstay of treatment for HIV/AIDS, even in older adults. Older adults with HIV/AIDS who are receiving HAART appear to have similar clinical responses to treatment despite a possibly slower immunologic response, in part due to higher rates of adherence.33 However, treatment with HAART in older adults can be complicated, due to underlying comorbidities and a greater risk of toxicity and drug-drug interactions. HIV infection, and perhaps its treatment, may accelerate the aging process, resulting in several comorbidities that are now well associated with HIV in older adults, including coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, dyslipidemia, dementia, and osteoporosis. The management of HIV/AIDS in older adults has been reviewed in several recent articles.33-37

Clinicians should discuss issues of sexual health and practicing safer sex with all older adults, despite clinicians’ potential discomfort in obtaining sexual histories from elderly patients. (See Table III for interview strategies for obtaining the sexual and social history of older LGBT adults.13) The results of two large surveys, published in a 1994 study, showed that heterosexual older adults are very unlikely to use preventative measures during sexual intercourse, with 92% never using a condom.38 Even in the presence of a known risk factor for HIV, such as multiple sexual partners, a risky sex partner, or injection drug use, these subjects were one-sixth as likely to use condoms as younger adults. While the lesbian, gay, and bisexual seniors surveyed in this study reported better rates of safer-sex practices than heterosexual seniors, 9% never used condoms, 48% intermittently used condoms, and 40% had never been tested for HIV.38

Mental Health Issues

Research has documented the link between mental health disorders and discrimination. The coming-out process for an older LGBT person, who has lived most of his or her life in a hostile or intolerant environment, can induce significant stress and contribute to lower life satisfaction and self-esteem. Managing social stressors such as prejudice, stigmatization, violence, and internalized homophobia over long periods of time results in higher risks of depression, suicide, risky behavior, and substance abuse.39 LGBT populations, therefore, may be at increased risk for these and other mental disorders. There may be a higher lifetime prevalence of affective disorders in LGBT persons, but no difference in current prevalence of such disorders.4 However, while little is known about the actual prevalence of mental health disorders in LGBT adults, even less is known about the prevalence of mental health disorders in older LGBT adults.

Suicide rates are alarmingly high in young LGBT persons, and suicidality may persist throughout adulthood into old age. A 2001, self-administered survey of 416 lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults age 60 to 91 years found that 29% of subjects rarely considered suicide, 8% sometimes considered suicide, and 2% often considered suicide, while 12% of subjects had suicidal thoughts in the past year.40 Most, however, did not relate their suicidal thoughts to their sexual orientation. Notably, better mental health was predicted in part by a higher percentage of people who knew about the subjects’ sexual orientation.40

Transgender persons experience mental health problems, such as adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse, that are similar to those experienced by other persons who endure major life changes and discrimination. Some studies also suggest that the incidence of severe personality disorders, psychosis, and mental illness in transgender persons is higher, although very little research has explored mental health issues in this group.4

Perception of and Concern About the Aging Process

LGBT adults may approach the aging process differently from their peers, and this approach may also differ by gender. While some theories state that homosexuals are better able to cope with aging than heterosexuals due to the development of adaptive skills and the reconstruction of their identities during the coming-out process,41-43 a study published in 2005 found that 88% of younger gay men and 73% of older gay men felt that gay society viewed aging as a negative process.41 Lesbians, however, felt that lesbian society viewed aging in a positive manner. This difference may be due to the influence of youth and physical attraction in gay male subculture, thus subjecting older gay men to ageism from within their own community.41

A questionnaire involving a small sample of self-identified lesbian and gay persons over age 50 years indicated that the areas of concern related to aging were similar to those of the general aging population (such as loneliness, health, and income), with the additional fears of rejection by their children and grandchildren, uncertain support, and concerns of discrimination in healthcare, employment, housing, and long-term care.42 The LAIN survey of LGBT baby boomers found that 32% of gay men and 26% of lesbians identified discrimination due to their sexual orientation as their greatest concern about aging.11

Psychosocial Concerns

Discrimination is not only present in healthcare, but also exists in employment, housing, civil rights, federal laws, and organization policies, all of which must be accounted for when addressing the psychosocial needs of older LGBT adults.

Advance Care Planning

With the passage of new federal regulations that took effect January 2011, same-sex partners are now guaranteed hospital visitation rights and the ability to make medical decisions for their loved ones.44 However, a same-sex partner may still be unable to make medical decisions for his or her loved one if there is no documented power of attorney for medical decisions, or if the couple’s marriage/union is not recognized by their state. It is therefore important that healthcare providers initiate discussions regarding documentation of power of attorney for medical decisions for all same-sex couples. Other advance planning, such as wills, living wills, financial planning, long-term care facility planning, and advance directives, should also be suggested. In the LAIN survey, 51% of LGBT baby boomers had yet to complete wills or living wills.11 Without careful estate planning, a surviving partner would have no claim on his or her partner’s assets and might even have to pay inheritance tax on their joint assets, including their home.

Financial Concerns

The federal government does not recognize same-sex marriages or domestic partnerships, and therefore denies more than 1100 benefits and protections to same-sex couples. For instance, survivor or retirement benefits are denied to partners and children in an LGBT family at an estimated cost to elderly LGBT persons of $124 million a year in unaccessed benefits.5 Federal employees cannot provide health insurance for their same-sex partners or receive paid sick leave to care for a partner. The federal government also taxes such benefits if offered by a private employer. Job stability and the health insurance that comes with employment are also threatened for LGBT adults in the 29 states that do not have laws prohibiting employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and the 38 states that do not prevent discrimination based on gender identity.45 Tax laws on joint assets and regulations of 401(k) and pensions have discriminated against same-sex partners, estimated to potentially cost a surviving partner over $1 million during the course of a lifetime.5 When placing the spouse of a same-sex partner into a nursing home, there is usually no protection of joint assets, including their home.

Housing and Long-Term Care

By 2030, there will be an estimated 120,000 to 300,000 older LGBT adults living in nursing homes.46 Entering a long-term care facility is a particularly vulnerable and potentially dangerous time for this population. There is a significant amount of real or feared discrimination, from both the staff and from other residents of the facility.46 A survey of 127 LGBT adults found that 73% believed that discrimination exists in retirement settings, 60% believed that they would not have equal access to social and health services, and 34% believed that they would have to hide their orientation upon entry into a retirement facility.47 Fear of disclosure is a significant and unique concern of LGBT seniors who are entering long-term care facilities, and concealing one’s identity and key relationships may prevent them from receiving appropriate care, threatens the ability to make meaning of one’s life, and can be very damaging to one’s personal identity and emotional, psychological, and physical well-being.46

Support Networks and Caregiving

The LGBT literature discusses the importance of informal support networks, which can be extensive social networks of friends, and their friends’ close family members, who LGBT adults turn to for support in addition to, or instead of, their own biological family. Through the years, however, these networks can deteriorate, putting the LGBT senior at further risk of isolation.48,49 Services offered to the elderly need to understand and respect these support systems, as well as provide the support if it is lacking. LGBT older adults may also be less likely to utilize mainstream support services due to fear of discrimination or having to disclose their sexual orientation.49 LGBT older adults may benefit from specialized services or housing that is exclusive to the LGBT population; however, these services are often only available in larger communities, and all support services for the elderly should be able to provide care that understands and respects the unique needs of older LGBT adults.

Older LGBT adults may also be more likely to take on the role and the responsibilities of caregiver, with the LAIN survey indicating that 1 in 4 LGBT baby boomers provides regular care to parents, partners, adult children, friends, or others, as compared with 1 in 5 adults in the general population.11 In addition, 53% reported caring for relatives from their family of origin, 18% reported caring for partners, and a considerable amount of care was provided to friends (14%), unrelated persons (5%), and neighbors (3%). The survey also interestingly shows that unlike the general population, gay and bisexual men were as equally likely to be caregivers as lesbians and bisexual women. Men and women also performed equal roles and with a similar number of hours spent caregiving.11 These differences in caregiving performed by LGBT adults may be important to consider when screening for caregiver stress. LGBT caregivers may also experience unique stressors, such as dealing with policies, families, and other caregivers who were not sensitive to or supportive of the relationship. When a loved one dies, the surviving caregiver’s grief may go unrecognized or inadequately addressed if the relationship was not fully recognized or disclosed.49

Conclusions

Three to eight percent of elderly patients are LGBT, and these persons have specific medical, psychological, and social needs. Healthcare providers must identify their LGBT patients in a safe and sensitive manner, be sensitive to the specific challenges faced by this group, and provide the appropriate support and resources that address their needs. For additional resources to aid the provider in caring for older LGBT patients, please see Table VII.10 Many older LGBT adults have faced a lifetime of discrimination and health disparities, but it is never too late for healthcare professionals to provide the appropriate and compassionate care that this vulnerable group deserves.

Dr. Appelbaum and Dr. Simone have both received honoraria from the American Geriatrics Society and the American Academy of HIV Medicine for participation in the HIV and Aging Panel. Dr. Appelbaum has also received consulting and other fees from Abbott, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Merck, Tibotec, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Simone has also received honoraria from The Fenway Institute for development of an online teaching module for older LGBT health, and is a recipient of the Geriatric Academic Career Award from the Health Resources and Services Administration. Dr. Simone is from Harvard Medical School, the Division of Gerontology, Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, MA; and Dr. Appelbaum is from the Department of Clinical Sciences, Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, FL.

References

1. Makadon H. Improving health care for the lesbian and gay communities. N Engl J Med 2006;354(9):895-897.

2. Sell R, Becker J. Sexual orientation data collection and progress toward Healthy People 2010. Am J Public Health 2001;91(6):876-882.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25. Accessed February 2, 2011.

4. Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Findings and concerns. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association 2000;4(3):101-150.

5. Cahill S, South K, Spade J. Outing Age: Public Policy Issues Affecting Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders. Washington, D.C.: The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2000.

6. SAGE (Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders). Improving the lives of LGBT older adults. March 2010. http://sageusa.org/resources/resource_view.cfm?resource=183. Accessed January 31, 2011.

7. Bradford J, Mayer K. Demography and the LGBT population: What we know, don’t know, and how the information helps to inform clinical practice. In: Makadon H, Mayer K, Potter J, Goldhammer H, eds. The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2007:25-41.

8. Assistive Housing for Elderly Gays and Lesbians in New York City: Extent of Need and the Preferences of Elderly Gays and Lesbians. New York, NY: Brookdale Center on Aging of Hunter College and Senior Action in a Gay Environment; 1999.

9. Rosenfeld D. Identity work among the homosexual elderly. Journal of Aging Studies 1999;13(12):121-144.

10. Appelbaum J. Late adulthood and aging: Clinical approaches. In: Makadon H, Mayer K, Potter J, Goldhammer H, eds. The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2007:135-156.

11. MetLife Mature Market Institute. Out and aging: The MetLife study of lesbian and gay baby boomers: Lesbian and Gay Aging Issues Network of the American Society on Aging and Zogby International; 2006. www.asaging.org/networks/lgain/outandaging.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011.

12. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Guidelines for the care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. www.qahc.org.au/files/shared/docs/GLMA_guide.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011.

13. McMahon G, Makadon H. Cross cultural care: Focus on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Presented at: Academy Center for Teaching and Learning at Harvard Medical School; November 21, 2008, Boston, MA.

14. Lamberg L. Gay is okay with APA—Forum honors landmark 1973 events. American Psychiatric Association. JAMA 1998;280(6):497-499.

15. Schatz B, O’Hanlan K. Anti-Gay Discrimination in Medicine: Results of a National Survey of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Physicians. San Francisco, CA: American Association of Physicians for Human Rights; 1994.

16. Kaiser Family Foundation. National Survey of Physicians, Part 1: Doctors on Disparities in Medical Care. March 2002. www.kff.org/minorityhealth/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageID=13955. Accessed January 27, 2011.

17. Quam J, Croghan C. Evolving words, evolving categories: A challenge for LGBT aging research. OutWord 2008;14(4):1.

18. Behney R. The aging network’s response to gay and lesbian issues. Outword: Newsletter of the Lesbian and Gay Aging Issues Network 1994;1(2):2.

19. Institute of Medicine. Lesbian health: Current assessment and directions for the future. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1999.

20. Lauver DR, Karon SL, Egan J, et al. Understanding lesbians’ mammography utilization. Womens Health Issues 1999;9(5):264-274.

21. Silenzio VMB. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Top 10 things gay men should discuss with their healthcare provider. www.glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/Top%20Ten%20Gay%20Men.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011.

22. Benson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, Pau A, Holmes KK; CDC; National Institutes of Health; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Recommendations from the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep 2004;53(RR-15):1-112.

23. Perlman G, Drescher JA, eds. Gay Man’s Guide to Prostate Cancer. Binghampton, NY: Hayworth Medical Press; 2005.

24. Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, Whitlock E, Charney P, Carter RA. Sexual orientation and health: Comparisons in the women's health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med 2000;9(9):843-853.

25. O’Hanlan KA. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Top 10 things lesbians should discuss with their healthcare provider. www.glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/Top%20Ten%20Lesbians.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011.

26. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

27. Allison RA. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Top 10 things transgender persons should discuss with their healthcare provider. www.glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/Top%20Ten%20Trans.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011.

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Persons aged 50 and older. www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/over50/index.htm. Accessed January 27, 2011.

29. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al; HIV Incidence Surveillance Group. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA 2008;300(5):520-529.

30. Owens DK, Sundaram V, Lazzeroni LC, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection among inpatients and outpatients in Department of Veterans Affairs health care systems: Implications for screening programs for HIV. Am J Public Health 2007;97(12):2173-2178.

31. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-14):1-17; CE1-CE4.

32. Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Holodniy M, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of HIV screening in patients older than 55 years of age. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(12):889-903.

33. Simone MJ, Appelbaum J. HIV in older adults. Geriatrics 2008;63(12):6-12.

34. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 2008;3(3):453-472.

35. Bhavan KP, Kampalath VN, Overton ET. The aging of the HIV epidemic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2008;5(3):150-158.

36. Luther VP, Wilkin AM. HIV infection in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 2007;23(3):567-583, vii.

37. Smith RD, Delpech VC, Brown AE, Rice BD. HIV transmission and high rates of late diagnoses among adults aged 50 years and over. AIDS 2010;24(13):2109-2115.

38. Stall R, Catania J. AIDS risk behaviors among late middle-aged and elderly Americans. The National AIDS Behavioral Surveys. Arch Intern Med 1994;154(1):57-63.

39. Brotman S, Ryan B, Cormier R. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. Gerontologist 2003;43(2):192-202.

40. D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Hershberger SL, O’Connell TS. Aspects of mental health among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Aging Ment Health 2001;5(2):149-158.

41. Schope RD. Who’s afraid of growing old? Gay and lesbian perceptions of aging. J Gerontol Soc Work 2005;45(4):23-38.

42. Quam JK, Whitford GS. Adaptation and age-related expectations of older gay and lesbian adults. Gerontologist 1992;32(3):367-374.

43. Friend R. Gayging: Adjustment and the older gay male. Alternative Lifestyles 1980;3(2):231-248.

44. Dwyer D. Hospital visitation rights for gay, lesbian partners take effect. ABC News.com. January 19, 2011. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/hospital-visitation-rights-gay-lesbian-partners-effect/story?id=12642543&cid=yahoo_pitchlist. Accessed February 3, 2011.

45. Human Rights Campaign. Statewide Employment Laws & Policies. www.hrc.org/documents/Employment_Laws_and_Policies.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011.

46. Cohen HL, Curry LC, Jenkins D, Walker CA, Hogstel MO. Older lesbians and gay men: Long-term care issues. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2008;16(2):33-38.

47. Johnson MJ, Jackson NC, Arnette JK, Koffman SD. Gay and lesbian perceptions of discrimination in retirement care facilities. J Homosex 2005;49(2):83-102.

48. Kean R. Understanding the lives of older gay people. Nurs Older People 2006;18(8):31-36.

49. Hash K. Caregiving and post-caregiving experiences of midlife and older gay men and lesbians. J Gerontol Soc Work 2006;47(3-4):121-138.