Peer Reviewed

A 9-Year-Old Girl With Knee and Hip Pain

AUTHORS:

Elaine Walters, MD, and Daniel A. Thimann, MD

CITATION:

Walters E. Thimann DA. A 9-year-old girl with knee and hip pain. Consultant for Pediatricians. 2013;(12)7:321-324.

A 9-year-old girl with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of pain in her right knee and hip. She recalls that the pain had started in her right knee and had progressed up to her hip. One month after the pain had begun, the girl underwent knee and hip radiography as ordered by her primary care provider, who reported that the results were normal. The patient continued to have pain despite the use of ibuprofen.

Approximately 1 month before being seen in the ED, the patient began to walk with a limp. At that time, another series of hip and knee radiographs were done at a different ED, the results of which were reported as normal. Still, her knee and hip pain persisted and began to awaken her at night.

She denied any history of trauma to the knee or hip. In the past few months, she has had a poor appetite and has unintentionally lost 5 kg. She reports occasional night sweats.

Upon physical examination, the girl’s vital signs were within normal limits. HEENT, cardiac, lung, and abdominal examination findings all were benign. Results of the examination of upper extremities were normal. No edema or erythema was noted over the right knee or hip. The right knee was stable with full range of motion. The patient had mild tenderness over the right patella. The right hip had full range of motion, but she experienced pain with internal and external rotation. The area over the right groin and iliac crest was tender to palpation. She experienced pain with weight bearing and walked with a limp.

Radiographs obtained in the ED (Figures 1, 2, and 3) helped guide management and diagnosis.

Figure 1. Anteroposterior radiograph of the right knee.

Figure 2. Lateral radiograph of the right knee.

Figure 3. Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis.

What is the cause of this girl’s knee and hip pain?

Answer and discussion on next page

ANSWER: Ewing sarcoma

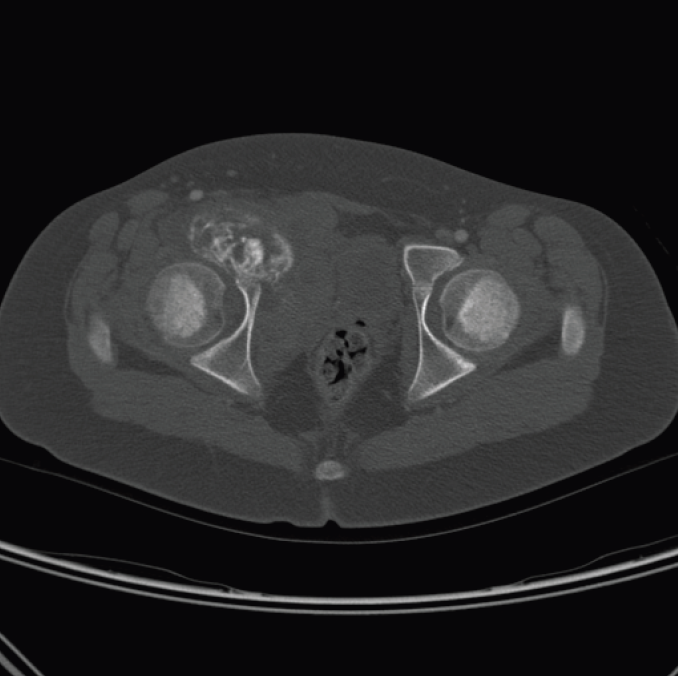

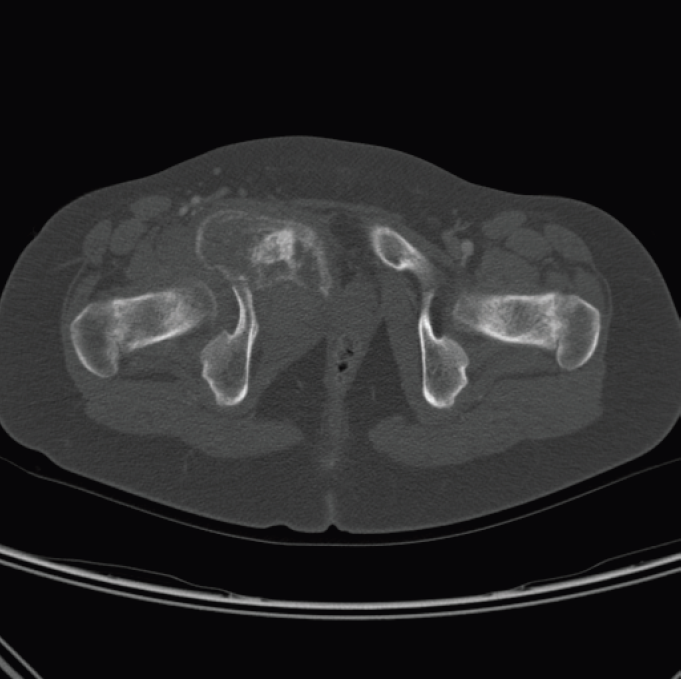

The radiograph of the girl’s pelvis (Figure 3) revealed onion-skin periostitis along the right superior pubic ramus. Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the pelvis was performed for further evaluation of the radiography findings. The CT images (Figures 4, 5 and 6) showed a permeative lesion that involved the entire right superior pubic ramus, with cortical destruction and onion-skin periostitis that were concerning for malignancy. The diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma was made.

Figures 4 and 5. Pelvic CT scan showed a permeative lesion involving the entire right superior pubic ramus.

Figure 6. Anteroposterior CT of the pelvis showed right-sided cortical destruction and onionskin periostitis of the superior pubic ramus, confirming the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma.

The patient initially was admitted to the oncology service for pain control. Further imaging revealed metastases to the lungs. The girl underwent chemotherapy and experienced improvement in her hip and knee pain, but she experienced a relapse 6 months after completing therapy.

Ewing sarcoma is the second most common bone tumor in the pediatric population, behind osteosarcoma. The incidence is approximately 2 to 3 cases per million annually in the United States, a figure that is largely unchanged from the 1970s. Ewing sarcoma occurs more commonly in the white population and affects males more often than females. Most cases are diagnosed in the second decade of life.1 It frequently affects the long bones and the axial skeleton, and it commonly metastasizes to the lungs and to other bones. The primary tumor has a similar distribution between the axial skeleton and long bones.

Malignancies of the Ewing family of tumors are small, round, blue-cell tumors and, in addition to Ewing sarcoma, include Askin tumor (tumor on the chest wall) and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Up to 95% of patients with Ewing sarcoma have the classic translocation between chromosomes 11 and 22.2

Patients with Ewing sarcoma usually present with persistent bone pain in the absence of trauma that is poorly responsive to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Some patients will have swelling and nighttime pain. Constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, fatigue, and night sweats also may be seen.

Initial evaluation consists of plain radiographs, which may show the characteristic lamellated onion-skin appearance.2 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred method for further evaluation of the primary bone tumor, and it should be performed before the biopsy, which may distort MRI findings and affect possible surgical debulking of the tumor. CT of the chest is the modality of choice for evaluation of pulmonary metastases.3 The Ewing sarcoma diagnosis ultimately is confirmed with local biopsy. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy also are performed, since bone metastases are common in Ewing sarcoma.

The differential diagnosis includes osteomyelitis, other bony malignancies, noncancerous bony lesions, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and Osgood-Schlatter disease.

Treatment of patients with Ewing sarcoma involves a multidisciplinary team. Systemic chemotherapy is usually initiated prior to local control. Further imaging is used to assess the response to chemotherapy. Radiotherapy can be used as an adjunct to treatment, but it may have late adverse effects such as secondary malignancies. Survival rates have improved since the advent of chemotherapy, increasing to approximately 75% in patients with localized disease. In patients with metastatic disease, survival is better in patients whose metastases are limited to the lungs alone.1,4

REFERENCES:

- Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB Jr. Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30(6):425-430.

- Heare T, Hensley MA, Dell’Orfano S. Bone tumors: osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(3):365-372.

- Meyer JS, Nadel HR, Marina N, et al. Imaging guidelines for children with Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Bone Tumor Committee. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(2):163-170.

- Balamuth NJ, Womer RB. Ewing’s sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):184-192.