Parasitic Infections

Lice

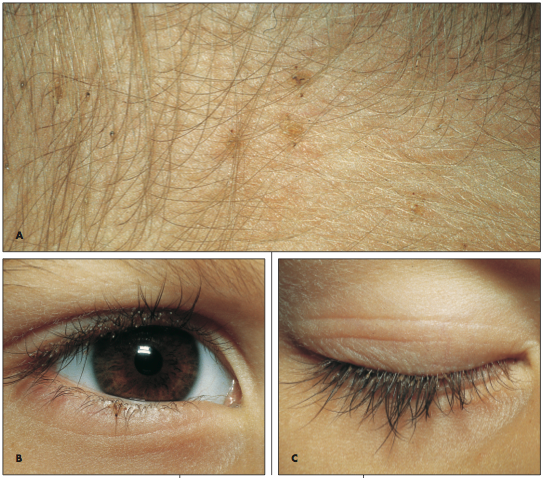

The mother of an asymptomatic 3-year-old girl noticed “bugs” on her daughter’s scalp. Figure A shows several head lice, Pediculus humanus capitis, at the lower posterior scalp. A louse was noted at the mid lower eyelid, just below the lashes (B); nits (ova) attached to the proximal upper eyelashes are seen (C).

Pruritus, which was notably absent in this case, is the hallmark of pediculosis. Head-to-head contact and shared combs, brushes, and towels are the usual modes of transmission. Head lice infestation is less common among black persons.

This child was treated with permethrin cream rinse, which kills adult lice and nits. Other treatment shampoos are pyrethrin and 1% lindane; these agents must be reapplied in 7 to 10 days to retreat the hatched larvae. Petrolatum was applied twice daily for 8 days to the patient’s eyelids to smother the ova and larvae. Physostigmine 0.025% and yellow oxide of mercury ophthalmic ointments may be used to treat the eyelashes.

Nits can be removed from the hair with a fine-tooth comb after a 1:1 vinegar and water rinse. Recommend that all of the patient’s clothing and bed linen be laundered in very hot water or dry cleaned. Brushes and combs must be discarded or treated in a pediculicide and washed in boiling water to prevent reinfection.

(Case and photographs courtesy of Dr Robert P. Blereau.)

Scabies

A 44-year-old man complained of a week-long rash and severe itching of his hands and buttocks. The pruritus was most intense at night. A fluocinolone cream had been tried, but the condition did not resolve.

Papules and excoriations were present on the patient’s buttocks and fingers (A). The finger webs, penis, and scrotum were spared. The nocturnal itch and failure of the topical corticosteroid suggested early scabies.

A high index of suspicion allows prompt detection and treatment of early scabies and prevents chronic disease that could persist for months or years. Early diagnosis and therapy also prevent transmission of the mite.

Bedtime application of lindane lotion and a shower the next morning were prescribed. The pruritus disappeared within 24 hours; the rash faded in 10 days (B).

(Case and photographs courtesy of Dr Dee Wee Lim.)

Ascariasis

A 30-year-old woman had had no medical problems until she suffered a 4-week bout of coughing, wheezing, and fever while traveling in Indonesia. This was followed by diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant, and anorexia. She returned to the United States, and her symptoms partially subsided. She sought no medical care at that time.

During a trip to Japan 3 years later, she had occasional attacks of diarrhea that contained bright red blood. This was attributed to external hemorrhoids. Returning to the United States about a year later, she continued to experience abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea. The following year, the diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting increased, and she lost weight. The diarrhea was worse at night, often awakening her.

The patient finally consulted a gastroenterologist 6 months later. Results of stool studies were negative for organisms, and findings from flexible sigmoidoscopy were within normal limits. Biopsy of the colonic mucosa revealed lymphoid aggregates. A subsequent upper GI series showed multiple ascarides in her stomach, duodenum, and small intestine. Within days, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed but revealed no evidence of ascarides. The patient was treated with pyrantel pamoate, and her symptoms finally resolved.

Ascaris lumbricoides is harbored by 25% of the world population, including 4 million Americans. It is the largest nematode (15- to 45-cm long) that infects humans and is found predominantly in the jejunum, maintaining its position there with its intense muscular activity.

The typical A lumbricoides lives for 1 year, and each adult female produces about 200,000 eggs daily. Following fertilization, the eggs develop in moist soil before being ingested by the human host. The life cycle of these worms involves a 2-step process: an early, extraintestinal pulmonary phase followed by a prolonged intestinal phase. They hatch in the small intestine, then migrate through the intestinal wall and travel to the lungs via the bloodstream or lymphatics. About 10 days later, they ascend the tracheobronchial tree, are swallowed, and return to the small intestine to complete their maturation 14 days later.

A lumbricoides does not manifest itself clinically, but 3 clinical syndromes can occur. The pulmonary phase (4 to 16 days after ingestion) involves cough, fever, wheezing, dyspnea, and angioedema or urticaria. In the GI phase, patients have vague abdominal discomfort, colic, and occasional diarrhea. Complications of ascariasis include intestinal obstruction, usually in the ileum; not uncommonly, the worms migrate into the biliary ducts, producing a picture of acute cholangitis or hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Less frequent complications include appendicitis, intestinal perforation, peritonitis, liver abscess, and obstruction of the upper respiratory tract.

The diagnosis of A lumbricoides infection is usually made by demonstrating embryonated and unembryonated eggs and adult worms in the feces, although this patient’s stool studies were negative. In addition, an upper GI series with small bowel follow-up can be diagnostic—as it was in this case. After the patient’s bowel is emptied of barium, A lumbricoides may be identified by its barium-filled intestinal tract.

All patients who acquire worms need to be treated because of the danger of complications. Give pyrantel or mebendazole; piperazine is an inexpensive alternative. Do not use mebendazole or piperazine in pregnant women.

(Case and photographs courtesy of Drs Armand Cacciarelli, James Robilotti, and Emma Bell.)

Filariasis

A 55-year-old woman with a 20-year history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension was admitted for elective cholecystectomy. She had had progressively increasing swelling of the legs for 30 years; she also complained of repeated cellulitis.

The patient—an immigrant from Antigua—reported that her sisters had similar leg swelling during early adulthood. Their condition was diagnosed as elephantiasis (lymphedema caused by filariasis).

In patients with lymphedema, impaired lymphatic drainage allows interstitial fluid to accumulate. Classically, the condition causes nonpitting edema.

Primary lymphedema is thought to arise from inherent lymphatic malformation; it is more prevalent among women than among men. Secondary lymphedema—progressive obliteration of lymphatics resulting from inflammation—may be caused by recurrent cellulitis, lymphatic obstruction secondary to malignancy, and in tropical countries, parasitic infection. Culprit organisms include 3 filarial nematodes: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Onchocerca volvulus.

Untreated lymphedema usually worsens over time and leads to physical impairment—such as difficulty in walking—and to psychological sequelae. Instruct your patients with this condition to take meticulous care of their feet to prevent lymphangitis. Graded pressure stockings and physical exercise may be helpful. Specialized pneumatic pumps can be tried; these devices help reduce the edema by opening gaps between terminal lymphatic junctions, allowing the fluid to flow. Surgery may be appropriate for patients who do not respond to other therapies.

(Case and photograph courtesy of Drs Manjula Thopcheria, Sonia Arunabh, and Arunabh.)

Echinococcosis

A 79-year-old woman who had a prosthetic mitral valve came to the emergency department (ED) because of severe hypotension; the cause was determined to be an acute upper GI hemorrhage.

During the workup in the ED, a palpable nontender mass was discovered in the right upper quadrant. An anteroposterior flat plate of the chest and abdomen revealed incidental large calcific densities within the liver (arrows) and pelvis. These proved to be hydatid cysts, a parasitic infection rarely seen in the United States, which frequently involves the liver. When the patient was questioned, she gave a history of extensive travel in the Middle East and South America.

Hydatid cysts represent the larval form of Echinococcus granulosus, a small tapeworm found in the intestinal tract of dogs and intermediate hosts (eg, sheep, cattle, and camels). When the ova are ingested by humans, they migrate to the liver or other organs, where they produce a round or oval density. These cysts are composed of a thick outer membrane and a thin inner wall of germinal cells. Over time, fluid fills and distends the cyst, and the resultant growth pattern resembles that of a neoplasm.

These abdominal cysts may be found in the liver or spleen but rarely in the kidney, bladder, ovary, or prostate. They also can occur in the brain, bones, thyroid, and lung, but they rarely calcify within the lung.

Echinococcosis is most commonly discovered by routine x-ray examination. Specific diagnosis is accomplished by histologic examination; do not attempt diagnostic

aspiration because of the potential for anaphylactic reactions to leakage of cystic fluid and hydatid “sand.” Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay provides the most sensitive and specific serologic diagnosis. Surgery remains the standard treatment for patients with hydatid cysts, although medical therapy with high-dose mebendazole may be considered for those who are not surgical candidates or who have extensive disease.

(Case and photograph courtesy of Drs Philip Munschauer, Leslie Trope, and William Bailey.)