Peer Reviewed

Accidental Barbie Doll–Related Vaginal Laceration in a 7-Year-Old

AUTHORS:

Paige Condit, MD

Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin

Jennifer Schramm, MD

Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC

Debra Esernio-Jenssen, MD

Department of Pediatrics, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, Pennsylvania

Dobie L. Giles, MD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin

Barbara L. Knox, MD

Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin

CITATION:

Condit P, Schramm J, Esernio-Jenssen D, Giles DL, Knox BL. Accidental Barbie doll–related vaginal laceration in a 7-year-old. Consultant. 2020;60(2):54-57. doi:10.25270/con.2020.02.00005

A 7-year-old girl was transferred from an outside hospital to an emergency department (ED) for further evaluation of vaginal bleeding. Reportedly, the child’s introitus had been penetrated when she had fallen onto the leg of a Barbie doll that was extended upward as she was exiting the bathtub. Because possible sexual abuse was suspected, a child abuse pediatrician from the hospital’s child protection program (CPP) was consulted.

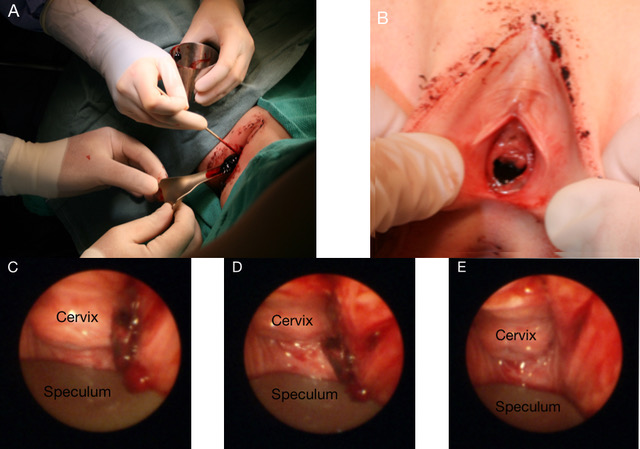

History. The child disclosed to the child abuse pediatrician that she had been playing in the bathtub with her twin sister and several Barbie dolls while showering. As she had attempted to exit the tub, her foot had slipped on one of the dolls, causing her to fall onto the raised leg of another doll (Figure 1). The child further stated that the leg of the doll was pointing toward the ceiling, and that it did “go into my body.” She stated that as a result, she screamed in pain.

Figure 1. The scene of the bathtub and Barbie dolls as recreated by the child. Note that one doll has its leg pointed upward, consistent with its position during impalement.

The child was able to correctly identify the parts of her body that are considered “private.” She did not report anyone having touched her private parts or having touched her in a manner that made her feel uncomfortable. The child also stated that she attends first grade and is an excellent student.

The child’s mother reported that she had heard her daughter’s “bloodcurdling screams” from another room. Upon running to the bathroom, she discovered her daughter squatting over the Barbie doll screaming. She then carried her to the bed in order to examine her genital area. She noted a large amount of blood coming from her daughter’s vaginal area and thus took her to an urgent care facility. A gynecologist who examined the child diagnosed a vaginal laceration. The girl was subsequently transported to a tertiary care center for intraoperative treatment.

The child was the product of a full-term twin pregnancy with cesarian delivery. Her medical history was significant for cystic fibrosis and common variable immune deficiency. Both disorders had been well controlled with standard treatments. The child lived at home with her biologic parents, her twin sister, an older sister (age 10) and 2 foster children (ages 2 and 8). There had been no prior concerns for abuse or neglect.

Physical examination. The child abuse pediatrician found no bruising of the child’s hymen and no transections or abrasions. Large clots of blood were present in the vaginal vault. The rugal folds were normal without fissures, tears, or scars. The remainder of the physical examination findings were normal. The child was admitted for examination under anesthesia (EUA) to elucidate the origin of the clots.

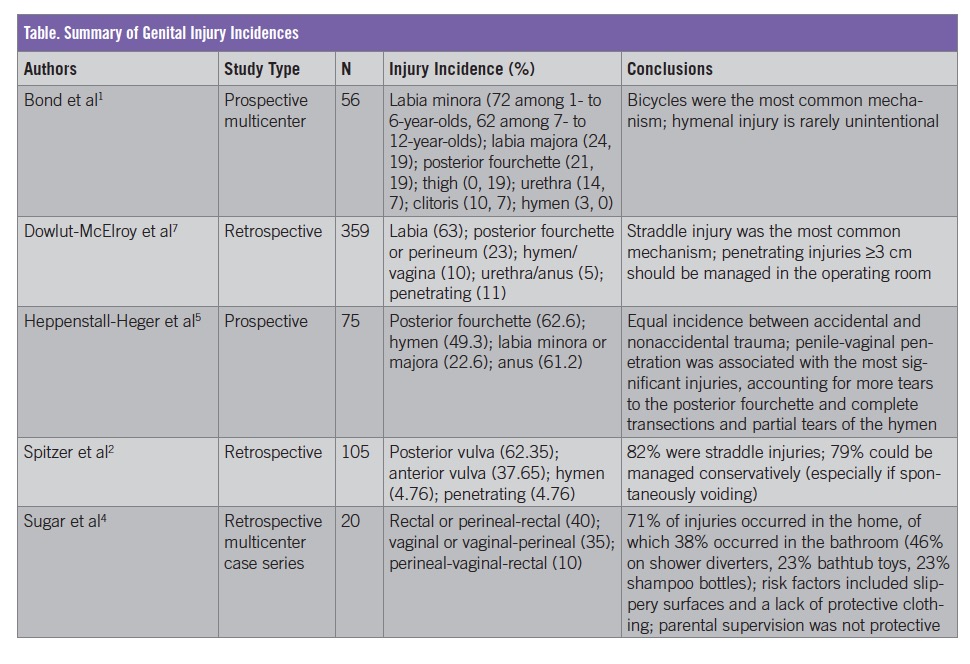

EUA reaffirmed the lack of injury to the labia, hymen, and posterior fourchette. (Figures 2A and 2B). Approximately 100 mL of clots were noted on vaginoscopic examination and were subsequently removed. The examination also revealed a 1-cm left vaginal sidewall laceration in the upper third of the vagina, to which a hemostatic agent was applied (Figures 2C-2E). The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Figure 2. (A) Large clots were removed from the girl’s vagina. (B) Close-up view of the normal-appearing hymen with no transections or abrasions. (C) Initial view of the upper vagina and cervix. (D) Clot displaced to fully visualize base, which revealed a 1-cm laceration. (E) Full view of the upper vaginal laceration with relation to cervix.

Diagnosis. The child abuse pediatrician diagnosed this case as being consistent with the accidental mechanism as stated. The child’s corroborated history and physical findings were attributable to a vaginal laceration due to impalement on the leg of a Barbie doll.

Discussion. Penetrating vaginal injuries in children should always raise suspicion of abuse given the relative rarity of accidental vaginal injury.1,2 Numerous studies have shown that multiple patterns of injury can accompany accidental groin injuries, but most injuries are to the outer portions of the genitalia (eg, labia, posterior fourchette) rather than internal structures (eg, vagina) (Table).1-4

Bond and colleagues1 reported that accidental and nonaccidental perineal injuries accounted for 0.2% of all injuries to children younger than 15 years old in the pediatric ED. Other studies have reported that 1.8% to 25% of genital injuries in children are due to a penetrating mechanism of injury, depending on whether children with nonaccidental injuries were included in the cohort.1,2

The 5 mechanisms of vulvar and vaginal injury are straddle (75% of cases), accidental penetration (including foreign bodies), sexual abuse, tearing as a result of sudden abduction of lower extremities, and lacerations as a result of pelvic fractures.6 Accidental penetration injuries are more common among 2- to 4-year-olds. Penetration usually is a result of their curiosity and self-manipulation with relatively sharp objects (eg, pens, pencils).6 Impalement injuries are uncommon, and injury to the vaginal wall without external injury resulting from impalement is extremely rare.3 This case is unique in that it was an accidental impalement injury with vaginal laceration without external perineal findings.

Straddle injuries have been reported as the most common causes of accidental genital trauma, consistent with the most common mechanism of general vulvar and vaginal injury, and that involvement usually is isolated to the labia.7 Management of these injuries is a point of discussion, and determining whether cases require EUA in an operating suite is debated. In one retrospective series,7 the authors found that older age, transfer from another institution, penetrating injuries, injuries involving the hymen/vagina/urethra/anus, and injuries larger that 3 cm were factors that increased the likelihood that the patient would require EUA in an operating suite.

Vaginal impalement injuries are likely to cause injury to surrounding organs due to the vagina’s anatomical structure and location —the rectovaginal septum is relatively thin, the urogenital diaphragm is superficial, and the bladder, uterus and rectum are low-lying.6 Injuries to the genitalia of young children are also likely to be more severe than in adults. Hymenal tissues in young children are unestrogenized and therefore lack distensibility. Additionally, the vaginal tissue capillaries are more exposed.2 These factors further support the rarity of an isolated vaginal laceration in the setting of accidental vaginal penetration.

In general, most injuries to the genitalia heal with minimal evidence of prior injury.5 Without surgical management, the most common findings after healing of hymenal injury were hymenal edge variations (eg, notches, lacerations, transections) and after posterior fourchette injuries were labial fusion or vascular changes.5

Evaluation of perineal injuries requires attention to detail and sensitivity. Experts recommend examination of external genital structures using a combination of positions (frog-leg, knee-chest, lateral decubitus), preferably in a caretaker’s arms, and with sedation if necessary.8 Instrumentation with Pederson speculum, vaginoscopy, or rectoscopy should be done under anesthesia with a complete anogenital examination.8 Examination of internal structures is essential, because a lack of significant external injuries may coexist with more serious internal injuries.3 Urinalysis and a voiding trial (where the patient urinates without pain or functional issues), are also recommended. Normal findings signal that conservative management, including sitz baths and barrier creams, likely will be successful.2,4 The patient in this case was instructed to take warm baths without soap twice daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ultimately, it is the clinician’s clinical judgment about whether the proposed mechanism of injury is consistent with the findings seen in determining whether or not to report hymenal, vaginal, or other genital injuries to Child Protective Services or law enforcement as a mandated reporter. Considerations include consistency between the history and the reported mechanism of injury, corroboration by other witnesses, and evaluation of the scene and objects involved.4

- Bond GR, Dowd MD, Landsman I, Rimsza M. Unintentional perineal injury in prepubescent girls: a multicenter, prospective report of 56 girls. Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):628-63

- Spitzer RF, Kives S, Caccia N, Ornstein M, Goia C, Allen LM. Retrospective review of unintentional female genital trauma at a pediatric referral center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):831-835.

- Grisoni ER, Hahn E, Marsh E, Volsko T, Dudgeon D. Pediatric perineal impalement injuries. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(5):702-704.

- Sugar NF, Feldman KW. Perineal impalements in children: distinguishing accident from abuse. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(9):605-616.

- Heppenstall-Heger A, McConnell G, Ticson L, Guerra L, Lister J, Zaragoza T. Healing patterns in anogenital injuries: a longitudinal study of injuries associated with sexual abuse, accidental injuries, or genital surgery in the preadolescent child. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):829-837.

- Jones JG, Worthington T. Genital and anal injuries requiring surgical repair in females less than 21 years of age. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21(4):207-211.

- Dowlut-McElroy T, Higgins J, Williams KB, Strickland JL. Patterns of treatment of accidental genital trauma in girls. J Pediatr and Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31(1):19-22.

- Benjamins LJ. Genital trauma in pediatric and adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(2):129-133.