Bullous Oral Erosions: Clues to Identifying—and Managing—the Cause

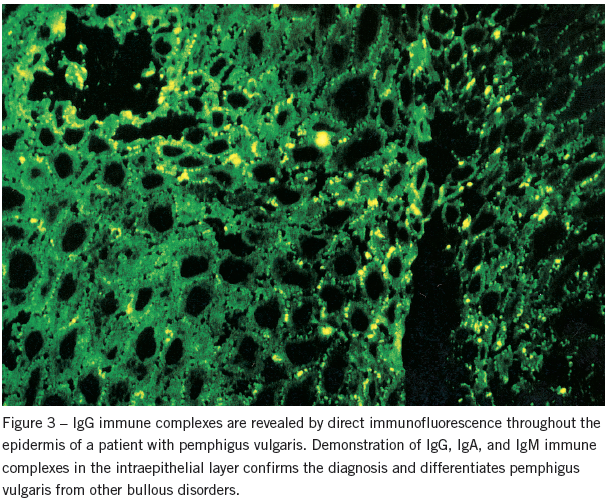

ABSTRACT: Certain clues can help you identify the cause of bullous oral lesions. Diffuse oral and labial bullous erosions, sometimes accompanied by target skin lesions, are diagnostic of erythema multiforme. In many conditions, however, the oral lesions themselves are nonspecific, and biopsy (which should be perilesional to include intact epidermis) is required. On light microscopy, the level of epithelial cleavage often suggests the diagnosis, especially for pemphigus vulgaris—a potentially fatal condition. Perhaps more importantly, a portion of the biopsy specimen should be sent for direct immunofluorescence, since many of these conditions are autoimmune and the type and location of the immune complexes present are diagnostic. For example, demonstration of IgG, IgA, and IgM in the intraepithelial layer confirms the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.

Key words: erythema multiforme, pemphigus vulgaris, epidermolysis bullosa, familial benign pemphigus, Hailey-Hailey disease, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Lyell’s syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, bullous pemphigoid, mucous membrane pemphigoid, erosive lichen planus, linear IgA disease, dermatitis herpetiformis

When your patient complains of painful extensive areas of denuded oral mucosa, a history of initial blistering suggests bullous oral lesions. Another clue is that such lesions have a larger area of mucosal erosion or ulceration than do punctate lesions.

The preliminary bullae, which are transient in the moist oral environment, rupture and leave an irregular erythematous patch. Fragments of the sloughed epithelium often remain at the margins or form a central pseudomembrane.

Bullous lesions—the focus of this review—tend to be multiple and may involve the lips. They are essentially oral manifestations of dermatologic disorders, some of which may be life-threatening (Table 1).

This article concludes my series on oral lesions. Previous articles on white, pigmented, erythematous, and punctate lesions appeared in (respectively) the April, May, June, and October 2012 issues of CONSULTANT.

This article concludes my series on oral lesions. Previous articles on white, pigmented, erythematous, and punctate lesions appeared in (respectively) the April, May, June, and October 2012 issues of CONSULTANT.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

A family history is important in establishing the diagnosis of two genodermatoses that can cause bullous lesions: epidermolysis bullosa and familial benign pemphigus. In some conditions, the appearance and location of the skin lesions (dermatitis herpetiformis and familial benign pemphigus) or their character and extent (toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome) suggest the diagnosis. The oral lesions themselves are nonspecific, and biopsy is generally required for diagnosis.

Biopsy should be perilesional to include intact epidermis. On light microscopy, the level of epithelial cleavage often suggests the correct diagnosis, especially for pemphigus vulgaris, which is a potentially fatal condition. Perhaps more importantly, a portion of the biopsy specimen should be sent for direct immunofluorescence, since many of these conditions are autoimmune and the type and location of the immune complexes present are diagnostic (Table 2).

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Characterized by irregular, erythematous target lesions, this skin disorder occasionally includes oral manifestations. Some patients have mucosal lesions only; these large, irregular, extremely painful areas of erosion—which have reddened margins and are overlaid with slough—can cover the entire oral cavity. The lesions often become confluent, and it may appear as if the patient has ingested a caustic substance. The lips, which are usually involved, are covered by a fibrinous exudate (Figure 1).

Erythema multiforme can appear in both sexes and at any age, but it is more prominent in young men. The source generally remains unknown but appears to be related to bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; malignancy; irradiation; autoimmune disease; or allergy and/or drug sensitivity. Prominent among the causative drugs are the sulfonamides, which may induce a severe and potentially fatal reaction, especially among patients who are also taking methotrexate.

The clinical picture of diffuse oral and labial lesions and, possibly, target lesions on the skin is diagnostic. Microscopic examination reveals degeneration of the entire epithelium with subepithelial clefting and intense, acute, and chronic inflammatory infiltrates in the connective tissue.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a disseminated form of erythema multiforme that can occur in children and young adults; it can also occur as an allergic reaction among persons who are sensitive to sulfonamides. Bullous lesions cover the entire body, and the mucosa of the eye, mouth, and genitourinary tract can also be involved. Because of the possibility of secondary sepsis, this condition is potentially fatal. Management includes systemic corticosteroids, intravenous antibiotics, fluid replacement, and a topical corticosteroid ointment.

Patients with erythema multiforme are treated with systemic prednisone, 40 to 60 mg/d. Prescribe an emollient mouthwash, such as diphenhydramine syrup, for the oral symptoms of the disorder.

TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS (LYELL’S SYNDROME)

In this condition, areas of skin erythema and dark macules rapidly progress to massive loss of epidermis.1 Almost all patients (90%) have mucous membrane involvement, which occasionally precedes the cutaneous lesions. Extensive lesions develop in the oral cavity, oropharynx, conjunctiva, and anogenital area. In the mouth, painful mucosal erosions and crusting of the lips appear. Fever and sepsis with multisystem involvement may occur.

While the clinical picture resembles erythema multiforme, it is unsettled whether toxic epidermal necrolysis is a severe form of this condition or a totally separate entity. Virtually all cases are related to drug exposure, and a hypersensitivity reaction is believed to be the cause. There is no evidence that an immune mechanism is operative; the results of virtually all direct immunofluorescent studies have been negative. The drugs principally involved are sulfonamides, phenytoin, barbiturates, NSAIDs, and allopurinol.

There is no specific treatment for toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, supportive management in a burn unit is recommended. Corticosteroid therapy is controversial.

PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS

This autoimmune disorder, which generally appears in middle age, affects skin and mucous membranes and is characterized by bullae of various sizes. The oral cavity is almost invariably involved in pemphigus vulgaris, and these lesions are often the first manifestation. Oral bullae are transient; the usual picture consists of multiple nonspecific erosions, mainly on the soft palate and buccal mucosa, with fragments of surface epithelium at the borders (Figure 2). Occasionally, a desquamative gingivitis is seen, and the oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx may be involved. Pain is the predominant symptom.

Widespread skin ulcerations of pemphigus vulgaris can lead to systemic sepsis and death. In a 20-year study of 107 patients who were treated with corticosteroids, Rosenberg and colleagues2 found a 32% mortality rate. High-dose corticosteroid therapy was a major cause of morbidity and mortality. This led to the use of adjunctive agents (see below) to reduce the corticosteroid dosage necessary for remission.

Microscopic examination of tissue removed from the lesion’s margin shows clefting of the epithelium above the stratum germinativum and acantholytic (Tzanck) cells within the fluid-filled space that develops. A variable degree of inflammatory infiltration occurs in the submucosa.

Nevertheless, evidence of epithelial loss and inflammatory infiltration does not establish a definitive diagnosis. This is best done by direct immunofluorescence. Demonstration of IgG, IgA, and IgM immune complexes in the intraepithelial layer confirms the diagnosis and differentiates pemphigus vulgaris from other bullous disorders (Figure 3).

When indirect immunofluorescence is used during the active stage, the serum is positive for immune complexes in 95% of cases. In remission, the titer is lower or even normal. Consequently, indirect immunofluorescence may be used to monitor the effectiveness of drug therapy.

Prescribe high-dose corticosteroids (60 to 180 mg/d) to induce remission. This dosage can be reduced with use of an adjunctive agent, such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, dapsone, or methotrexate. Follow up patients because pemphigus vulgaris is associated with thymic neoplasms.

BULLOUS PEMPHIGOID

Although this autoimmune condition resembles pemphigus vulgaris, it has different features (Figure 4). These include a decreased incidence of oral lesions; their development after, rather than before, that of skin lesions3; the nature of the oral lesions; and the histologic picture. The mean age of incidence is in the sixth and seventh decades.

Although most lesions consist of bullae, there may also be vesicles. The distribution of the oral lesions is similar to that seen in pemphigus vulgaris. In an analysis of 25 cases, Laskaris and co-workers3 reported involvement of buccal mucosa in 52%, soft palate in 40%, tongue in 24%, lower lip in 20%, gingiva in 16%, upper lip in 8%, and floor of the mouth in 8%. The intense, widespread, desquamative gingivitis in bullous pemphigoid is of diagnostic importance.

Histologic examination shows subepithelial bullae with cleavage at the epithelial–connective-tissue junction. The epithelium is normal. Acantholysis is absent, and the submucosa shows an intense inflammatory reaction. The diagnosis is confirmed when direct immunofluorescence reveals immune complexes binding IgG and C3 in the epidermal basement membrane.

Treat patients who have bullous pemphigoid with systemic corticosteroids, 40 to 80 mg/d. As with pemphigus vulgaris, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, dapsone, or methotrexate can be used as adjunctive therapy.4

MUCOUS MEMBRANE PEMPHIGOID

The conjunctiva and oral cavity are the primary sites of involvement here; however, mucosal lesions have been reported in the nose, pharynx, esophagus, larynx, urogenital tract, and anus, as well as the skin. The incidence of ocular involvement ranges from 10% to 62% in different studies.3,4

Mucous membrane pemphigoid lesions are vesiculobullous and often heal with scarring (hence the term “cicatricial pemphigoid”), except in the oral cavity. Adhesions commonly occur in the eye (symblepharons). The mean age of occurrence is 60, and women are affected two to three times as often as men. The disease generally is chronic, but protracted intervals of remission may occur.

In a series of 85 cases reviewed by Sklar and McCarthy,5 regional involvement included the oral cavity (100%), conjunctiva (59%), genitalia (20%), skin (9%), nose (8%), rectum (5%), urethra (5%), and esophagus (3%). In their series of 65 cases, Silverman and colleagues6 reported that the most common sites of oral involvement were the gingiva (94%), palate (32%), buccal mucosa (29%), floor of the mouth (5%), and tongue (5%). In my practice, I have also seen lesions in the oropharynx and larynx; these generally occurred in conjunction with oral cavity involvement.

The oral lesions of mucous membrane pemphigoid are generally smaller than those of pemphigoid vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid, and they develop more slowly. As in bullous pemphigoid, the lesions are often accompanied by an intense erythematous and desquamative gingivitis (Figure 5). Similarly, the histologic picture shows subepithelial clefting of the mucosa without acantholysis and with an intense inflammatory infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of immune complexes binding IgG and C3 in the basement membrane.

Although tissue studies may not differentiate mucous membrane pemphigoid from bullous pemphigoid, the clinical picture is helpful. The intense oral and ocular involvement and scarcity of skin lesions found in mucous membrane pemphigoid differ from the infrequent oral lesions and extensive skin involvement seen with bullous pemphigoid.

For local pain control, prescribe an emollient mouthwash, such as diphenhydramine syrup. Use systemic prednisone (20 to 40 mg/d) as well.

PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS

This autoimmune vesiculobullous disorder is associated with an underlying neoplasm: most commonly, lymphoma, leukemia, sarcomas, and thymoma.7 The oral lesions resemble those of pemphigus; severe involvement of the lips is almost universal. Lichenoid and bullous lesions may occur on the skin, and conjunctival changes mimic those associated with cicatricial pemphigoid.

On microscopic examination, there is acantholysis with epithelial clefting; on direct immunofluorescence, IgG and complement deposits are present in the intercellular spaces of the epidermis and along the basement membrane. The detection of immunoglobulins with indirect immunofluorescence in the epithelium of the rat bladder yields a precise diagnosis. Treatment consists of corticosteroids and azathioprine (1 to 2 mg/kg/d).

BENIGN FAMILIAL CHRONIC PEMPHIGUS

Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this condition is an autosomal dominant genodermatosis in which there is a defect in keratinocytic adhesion.8 This chronic skin disease generally appears in the second and third decades of life with the formation of bullae in the intertriginous zones and on the neck. The bullae transform into circinate scaling plaques and then into infected, painful vegetations.

In the mouth, irregular bullae, which are initially indistinguishable from those of pemphigus vulgaris, appear on the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate. Some of these bullae become vegetations.

On microscopic examination, suprabasilar acantholysis is seen, which distinguishes this condition from pemphigus. In addition, the results of direct and indirect immunofluorescence are negative. Treat the skin lesions with topical antibiotics and corticosteroids and with oral antibiotics; use topical and intralesional corticosteroids for lesions in the oral cavity.

EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA

In this genodermatosis, cutaneous and oral mucosal subepidermal bullae appear during childhood following minor trauma. The severity depends on the genetic penetrance. The numerous variants can be contained in three broad categories, based on the level of tissue cleavage after trauma:

•Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (this type is epidermolytic).

•Junctional epidermolysis bullosa (lamina lucidolytic).

•Epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica (dermolytic).9

The extent of oral involvement ranges from small vesicles to large bullae, according to type. Numerous milia are also present in all three types.

Lesions can form anywhere in the oral cavity. The most serious involvement is caused by the recessive dystrophic type. Its severe scarring results in vestibular stenosis, ankyloglossia, and microstomia. Scarring is less common in the junctional and simplex types. Diagnostic points for epidermolysis bullosa include distribution of the skin lesions (over the arm and leg joints in the dystrophic form), oral and cutaneous scarring, family history, and onset in childhood.

Treatment is palliative. Nevertheless, phenytoin can decrease cutaneous blistering.9

EROSIVE LICHEN PLANUS

The erosive form of lichen planus, mentioned in the first article of this series (CONSULTANT, April 2012, page 301), is more common in women and white persons. The mean age at onset is 50. The involved sites are, in decreasing order, the buccal mucosa, tongue, gingiva, palate, lips, and floor of the mouth. Pain is the universal complaint.

These erosions generally arise from atrophic areas in the keratotic plaques, which undergo desquamation (Figure 6). Actual bullae rarely form. On microscopic examination, the epithelium is absent, and the underlying connective tissue has mixed acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates. When the epidermis is present, hydropic degeneration of the basal cells is seen, often with the formation of acidophilic (colloid) bodies in the adjacent dermis.

While immunoreactivity has been detected in the epidermal-dermal interface in patients with lichen planus, there is no definitive diagnostic pattern. Schiodt and associates10 found immunoglobulin activity in the basement membrane in 4% of 45 patients studied, with evidence of C3 in 33% and of fibrinogen in 91%. Among 35 patients with oral lichen planus, Laskaris and co-workers11 observed immunoglobulins in the epidermal-dermal junction in 25% and fibrin in 100%.

While immunoreactivity has been detected in the epidermal-dermal interface in patients with lichen planus, there is no definitive diagnostic pattern. Schiodt and associates10 found immunoglobulin activity in the basement membrane in 4% of 45 patients studied, with evidence of C3 in 33% and of fibrinogen in 91%. Among 35 patients with oral lichen planus, Laskaris and co-workers11 observed immunoglobulins in the epidermal-dermal junction in 25% and fibrin in 100%.

The most significant immunologic finding is the presence of IgM in the colloid bodies.12 However, these bodies are not pathognomonic, since they are also seen in patients who have discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), erythema multiforme, pemphigus, and pemphigoid, as well as in those who do not have any of these conditions.

Treat erosive lichen planus with topical (triamcinolone in an adhesive base) and systemic corticosteroids. Periodically reexamine patients because this disease is associated with squamous cell carcinoma.

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

SLE is an autoimmune disorder with visceral involvement that occurs primarily in young women. Discoid lupus denotes cutaneous involvement only, therefore implying a better prognosis. In both forms, the oral lesions can occur without cutaneous changes.

In a study of oral lesions in 32 patients with discoid lupus, Schiodt and colleagues13 found that the buccal and labial mucosa, gingiva, and lip were the principal sites of occurrence. The classic lesion is an erythematous patch with white striae radiating from the center.

SLE lesions can be white or red or may appear as bullous areas. In a study of the oral lesions in 23 patients with SLE, Jonsson and co-workers14 found that the sites of occurrence were, in descending order, the hard palate, buccal mucosa, lip, and alveolar ridges. The lesions were multicentric in half the cases.

The bullae are fleeting; more frequent manifestations are erythematous patches with whitish fragments of the sloughed epithelium at the margins or centrally (Figure 7). The lesion may also appear as an erythematous gingivitis and desquamative cheilitis.

A wide variety of changes can be seen microscopically, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, degeneration of the basal lamina, and subepithelial lymphocytic infiltrates. These findings are nonspecific and may be confused with those of lichen planus.

On immunologic testing, Schiodt and colleagues10 found IgG in the basement membrane area in 100% of 7 patients with SLE and in 73% of 45 patients with discoid lupus. These investigators also found activity for IgA (43%), C3 (100%), and fibrinogen (62%) in the basement membrane of the patients with SLE.

Jonsson and colleagues14 conducted immunologic studies in 10 patients with SLE. All had IgM, 7 had IgG, 6 had C3, 7 had fibrinogen, and 4 had cytoid bodies present in the basement membrane.

Because the clinical and histologic appearances of SLE lesions are nonspecific, base your diagnosis on positive results of an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and laboratory data that suggest multisystem disease. Treat patients with topical and systemic corticosteroid therapy.

LINEAR IgA DISEASE

In this autoimmune disorder involving the skin and mucous membranes, erosive lesions ranging from small ulcers to extensive areas of mucosal denudation develop in the mouth.15 This condition affects persons in midlife; oral ulcerations are occasionally the only finding.

The palate, tongue, and buccal mucosa are most commonly involved. Painful ulcers and desquamative gingivitis present a clinical picture indistinguishable from that of pemphigus vulgaris.

Diagnosis is by direct immunofluorescent study of biopsy specimens, which reveal linear deposits of IgA along the epidermal-dermal border. Linear IgA disease can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis (a condition in which the incidence of oral lesions is 50% to 70%) by the presence of granular deposits of IgA in the basement membrane and the absence of a history of gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Treatment consists of topical dexamethasone elixir, oral corticosteroids (prednisone, 40 to 60 mg/d), and dapsone (100 mg/d).

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS

This immune-mediated dermatologic condition is characterized by a symmetric, pruritic, papulovesicular eruption on the extensor surfaces of the body.16 The peak incidence is in the fourth decade of life, with a male preponderance.

Diagnosis is by direct immunofluorescence, which demonstrates granular deposits of IgA and complement components at the tips of the papillary dermis. Mouth lesions are uncommon; however, granular deposits of IgA are often found in the oral mucosa of patients who are clinically free of disease. Areas of erythema and superficial ulceration may develop, principally on the buccal mucosa and tongue.

Most patients (85%) have gluten sensitivity, and there is a strong association with the presence of HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA DqW2. Management consists of a gluten-free diet and dapsone at a suppression maintenance dosage of 100 to 200 mg/d.

CHRONIC ULCERATIVE STOMATITIS WITH STRATIFIED EPITHELIAL-SPECIFIC ANA

In this condition, recurrent or chronic ulcerations and erosions in the mouth have often been misdiagnosed as erosive lichen planus.17 The disorder generally arises in the fifth and sixth decades and involves the gingiva, tongue, and buccal mucosa. Perilesional biopsy reveals mononuclear cell infiltrates below the epidermis and vacuolar changes in cells at the mucosal-submucosal junction.

The immunologic findings are distinctive. Direct immunofluorescence shows a speckled ANA pattern in the lower third of the epidermis.18 In addition, high titers of stratified epithelial-specific antibody are present in the serum, which produce a similar pattern of staining in the esophagus of the guinea pig and monkey on indirect immunofluorescence. Treat mild cases with topical corticosteroids (dexamethasone elixir); in severe cases, hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/d) has been found to induce remission.

GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

This condition occurs after allogenic bone marrow transplantation as a result of immunocompetent donor lymphocytes reacting to antigens present in an immune-deficient host. In the acute form, which develops several days to a few months after transplantation, a morbilliform rash, palmar erythema, and oral lesions appear; they are often accompanied by fever, malaise, nausea, diarrhea, hepatitis, and xerostomia.

In the mouth, lichenoid, papular, and erythematous lesions appear; desquamation and ulceration are infrequent.19 Sites of predilection are the labial and buccal mucosa, the palate, and the dorsum of the tongue. The findings are nonspecific, and the oral findings may represent a composite of changes caused by radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drug therapy, and secondary infection (especially by herpes simplex virus).

The chronic form develops 3 to 12 months following the transplantation and involves the oral cavity in the majority of cases.20 Most commonly, there is erythema of the labial and buccal mucosa, palate, and lingual dorsum; less frequently, atrophy and lichenoid changes appear in these regions. Ulceration occurs in only a few patients—usually those with the most severe disease.

Treatment consists of systemic immunosuppressive therapy; prescribe corticosteroid rinses for patients with ulceration and pain.

SECONDARY SYPHILIS

This disease generally causes lymphadenopathy, skin eruption, fever, malaise, and oral lesions. The oral manifestation may take the form of a condyloma, or mucous patch. It typically appears on the buccal mucosa, tongue, and lips as a slightly elevated lesion with a grayish center, surrounded by an erythematous halo (Figure 8). Because this appearance is nonspecific, confirm the diagnosis with identification of spirochetes under dark-field microscopic examination of smears and/or by serologic test results positive for Treponema pallidum.

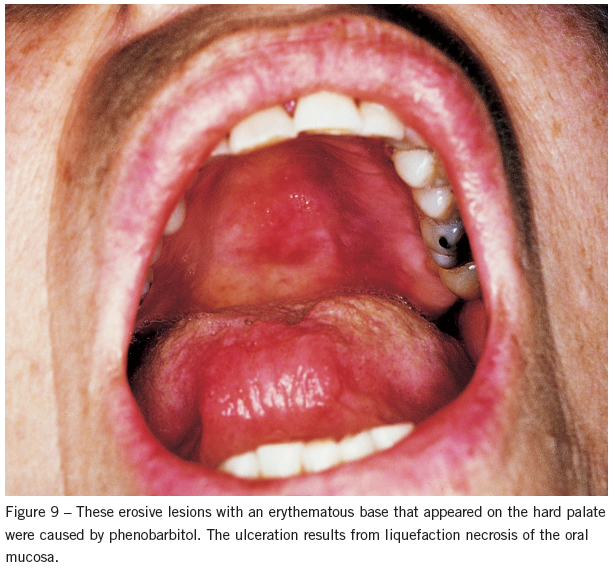

DRUG-INDUCED LESIONS

These may consist of large, irregular ulcerations of variable depth produced by liquefaction necrosis of the oral mucosa (Figure 9). They can arise anywhere in the oral cavity but are most common on the buccal mucosa and gingiva. Drugs can also induce acantholysis, producing a pemphigus-like clinical picture by immunologic mechanisms. These lesions are usually cutaneous, with the oral cavity rarely involved.

Causative agents include anti-inflammatory drugs used for rheumatoid disorders (eg, penicillamine, tiopronin, pyrazolone compounds, and gold), antihypertensives (eg, captopril and ß-blockers), antibiotics (eg, rifampin, penicillin, and cephalexin), barbiturates, and hormones (eg, progesterone).21 The presence of sulfhydryl groups is a common chemical feature shared by many of these drugs. In addition to discontinuing use of the offending agent, prescribe systemic corticosteroids to expedite healing.

REFERENCES:

1. Roujeau JC, Chosidow O, Saiag P, Guillaume JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome).

J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1039-1058.

2. Rosenberg FR, Sanders S, Nelson CT. Pemphigus: a 20-year review of 107 patients treated with

corticosteroids. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:962-970.

3. Laskaris GG, Sklavounou A, Stratigos J. Bullous pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid, and pemphigus vulgaris: a comparative clinical study of 278 cases. Oral Surg. 1982;65:656-662.

4. Korman NJ. Bullous pemphigoid. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:483-498.

5. Sklar G, McCarthy PL. The oral lesions of mucous membrane pemphigoid: a study of 85 cases.

Arch Otolaryngol. 1987;93:354-364.

6. Silverman S, Gorsky M, Lozadi-Nur F, Liu A. Oral mucous membrane pemphigoid: a study

of sixty-five patients. Oral Surg. 1986;61:233-237.

7. Helm TN, Camisa C, Valenzuela R, Allen CM. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a distinctive autoimmune vesiculobullous disorder associated with neoplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:209-213.

8. Botvinick I. Familial benign pemphigus with oral mucous membrane lesions. Cutis. 1973;12:

371-373.

9. Wright JT, Fine JD, Johnson LB. Oral soft tissues in hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. Oral Surg. 1991;71:440-446.

10. Schiodt T, Homstrup P, Dabelsteen E, Ullman S. Deposits of immunoglobulins, complement, and fibrinogen in oral lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, and leukoplakia. Oral Surg. 1981;51:

603-608.

11. Laskaris G, Sklavounou A, Angelopoulos A. Direct immunofluorescence in oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53:483-487.

12. Beutner EH, Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S. Clinical significance of immunofluorescence tests of sera and skin in bullous diseases: a comparative study. In: Beutner EH, Chorzelski TP, Kumar V, eds. Immunopathology of the Skin. 3rd ed. New York: J Wiley and Sons; 1987:

177-205.

13. Schiodt T, Halberg P, Hentzer B. A clinical study of 32 patients with oral discoid lupus erythematosus. Int J Oral Surg. 1978;7:85-94.

14. Jonsson R, Heyden G, Westberg NG, Nyberg G. Oral mucosal lesions in systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinical, histopathological and immunopathological study. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:

38-42.

15. Chan LS, Regezi JA, Cooper KD. Oral manifestations of linear IgA disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:362-365.

16. Zono J. Dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA bullous disease, and chronic bullous disease of childhood. In: Provost TT, Weston WL. Bullous Diseases. St Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1993:

157-212.

17. Beutner EH, Chorzelski TP, Parodi A, Schosser R. Ten cases of chronic ulcerative stomatitis with stratified epithelium-specific antinuclear antibody. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:

781-782.

18. Church LF, Schosser RH. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis associated with stratified epithelial specific antinuclear antibodies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:579-582.

19. Barrett AP, Bilous AM. Oral patterns of acute and chronic graft-v-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1461-1465.

20. Schubert MM, Sullivan KM, Merton TH. Oral manifestations of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1591-1595.

21. Mutasim DF, Pelc NJ, Anhalt GJ. Drug-induced pemphigus. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:463-469.md